FREE MARKET ECONOMY

Page 73

Page 74

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Twelve months after D-Day we take a look at how the country's deregulated PSV operations are performing — and the news is not all good.

• It is now a year since competition offiaally came to the bus business. The Government, which thinks running buses is like running a corner shop, predicted that a host of enterprising small businesses would spring up overnight. By contrast, the operators and their associations were full of dire predictions, and the bus-using public was apprehensive.

The first anniversary of deregulation is a good time to take stock of the PSV scene. Newcomers have indeed appeared — and some of them have already vanished. A few went through the preliminary legal processes, such as registration, but never even started. Others have retired defeated, and more competitors have only just begun.

The real surprises are where the toughest business battles are being fought — and who is fighting them. Like good generals most of the opposition appears to have studied their target cities, towns or areas long and hard before launching an attack. The prime contenders are not, on the whole, smaller firms or newcomers, but established operators challenging other established operators, sometimes a long way from their home bases.

ROUTE TENDERING

Deregulation was not only brought in to encourage competition on profitable routes. It has also imposed a requirement — a very fair requirement, many would agree — for any subsidised routes or even journeys to be put out to tender. In many cases an existing operator has registered its daytime Monday-Friday or Monday-Saturday services as commercial operations, but has left evening and Sunday operations to be covered by subsidies. Then it is up to the county transport co-ordinator to seek tenders for economic provision of these quiet runs, if the council sees the need and has the funds.

The results can be surprising. There are routes where a large operator runs a service commercially from Mondays to Saturdays, but evening operations on the same route are run by a small independent operator.

Then there are cases where a large operator has lost a daily subsidised weekday service to a newcomer, but has won it back on Sundays. All that this really proves is that many of the tenders are quite close, and just a few pounds a day could mean success or failure. Smaller operators generally seem to have been more successful in winning tenders for non-paying routes around smaller cities.

CONFUSING NUMBERS

One minor nonsense is in the well-ordered network of bus services in Surrey, where subsidised operations or even journeys have to bear a different route number. So what is normally route 422 can become 522, even when worked by the same operator and going to the same place. It seems an unnecessary, confusing distinction.

In the early days of deregulation some operators registered unprofitable journeys, and later gave notice of termination. No doubt the hope was that once initial interest died down there would be fewer tenderers, and they might win back their "own" route — it has not always worked out this way.

It has not always been newcomers who have got it wrong, either. Initially Greater Manchester took on numerous Sunday services in towns well beyond its traditional boundaries. Then it found that takings were very low, costs of operation and supervision were higher than expected, and it gave them all up.

In Scotland competition began early, particularly between the Scottish Bus Group and Strathclyde Buses. SBG had prepared itself for the fray by reorganising territories with more, smaller companies.

Where the new company was previously just a part of a larger one the idea seems to have worked, but where a new company was formed out of several bits of different companies — as, for example, Kelvin Scottish — it has not been so easy. SBG has subsequently had to announce cut-backs of fleets and staff, often in the order of 10%. Strathclyde in particular has proved a tough competitor.

One SBG idea that has had considerable success, and has been widely copied, is a return to open-platform buses with conductors. Clydeside Scottish is the biggest user of former London Routemasters and two other SBG companies also run them. They were, of course, relatively cheap to buy and are short, making them very manoeuvrable, while in a depressed labour market it is easy to recruit conductors.

Their success is also linked to SBG's exact fare/no change policy. Several SBG companies make capital out of their willingness to give change, but that is perhaps making a virtue out of necessity. Giving change may be popular with the public, but it does slow up the operation of any one-person bus, to the ultimate detriment of the passengers. That in turn increases the number of buses needed to meet a given demand, and therefore reduces the operator's profit.

EXPENSIVE STAFF

Nonetheless, taking on extra full-time crew members is expensive, and therefore only practical on busy city services with high potential earnings, or maybe as a short-term measure for a year or two to frighten off the competition.

Fare cutting has not been as prevalent as might have been expected. There have been some instances — indeed there have even been some operations where, for a time, no fares have been charged — but in some larger cities competing operators accept multi-journey tickets or season tickets valid on all operators' buses. Such takings are shared on an agreed basis.

One of the stranger examples of competition can be found in Newcastle upon Tyne. Part of the deregulation provisions forced all passenger transport executives and municipalities to set up separate freestanding companies to run their buses on a profitable, or at least no-loss basis.

The bus side of the Wear PTE established itself as Busways Travel Services, with individual divisions known as City Busways, Newcastle Busways and various other Busways. This was a good marketing ploy, but then a newcomer came along, with five frequent city services in Newcastle. Although owned by another well-known operator, Trimdon Motor Services, it trades as Tyne & Wear Omnibus Company. Like Go-Ahead Northern, the Metro, the British Rail line to Sunderland, the ferries, Northumbria Motor Services and many smaller operators, Tyne & Wear Omnibus accepts the co-ordinated Travefticket zone scheme which the old PTE launched in 1975. Busways, however, has opted out of part of the scheme, and will only, accept the dearer, all-zones Travelticket, and has chosen to promote its own Faresaver season ticket which can only be used on its own services. Over 218 million a year is spent on the Traveltickets, so they are obviously of value to most of Newcastle's population — but they are no longer valid on what was the PTE's own bus operation. Understandably, many local bus users find it all very confusing.

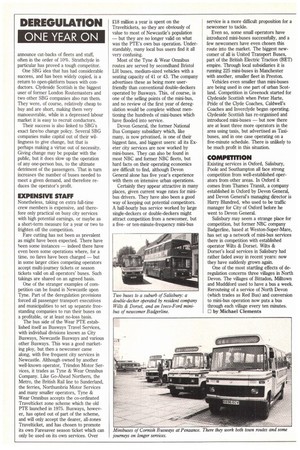

Most of the Tyne & Wear Omnibus routes are served by secondhand Bristol LH buses, medium-sized vehicles with a seating capacity of 41 or 43. The company advertises these as being more userfriendly than conventional double-deckers operated by Busways. This, of course, is one of the selling points of the mini-bus, and no review of the first year of deregulation would be complete without mentioning the hundreds of mini-buses which have flooded into service.

Devon General, the former National Bus Company subsidiary which, like many, is now privatised, is one of their biggest fans, and biggest users: all its Exeter city services are now worked by mini-buses. They can also be found in most NBC and former NBC fleets, but hard facts on their operating economics are difficult to find, although Devon General alone has five year's experience with them on intensive urban operations.

Certainly they appear attractive in many places, given current wage rates for minibus drivers. They have also been a good way of keeping out potential competitors. A half-hourly bus service worked by large single-deckers or double-deckers might attract competition from a newcomer, but a fiveor ten-minute-frequency mini-bus service is a more difficult proposition for a newcomer to tackle.

Even so, some small operators have introduced mini-buses successfully, and a few newcomers have even chosen this route into the market. The biggest newcomer of all is United Transport Buses, part of the British Electric Traction (BET) empire. Through local subsidiaries it is running 225 mini-buses in Manchester with another, smaller fleet in Preston.

Vehicles even smaller than mini-buses are being used in one part of urban Scotland. Competition in Greenock started for Clydeside Scottish when Peter Harte, Pride of the Clyde Coaches, Caldwell's Coaches and Inverclyde began operating. Clydeside Scottish has re-organised and introduced mini-buses — but now there are at least three more operators in the area using taxis, but advertised as Taxibuses, and in one case operating on a five-minute schedule. There is unlikely to be much profit in this situation.

COMPETMON

Existing services in Oxford, Salisbury, Poole and Southampton all face strong competition from well-established operators from other areas. In Oxford it comes from Thames Transit, a company established in Oxford by Devon General, and Devon Generals managing director is Harry Blundred, who used to be traffic manager for City of Oxford before he went to Devon General.

Salisbury may seem a strange place for competition, but former NBC company Badgerline, based at Weston-Super-Mare, has set up a network of mini-bus services there in competition with established operator Wilts & Dorset. Wilts & Dorset's local services in Salisbury had rather faded away in recent years: now they have suddenly grown again.

One of the most startling effects of deregulation concerns three villages in North Devon. The villages of Bittadon, Milltown and Muddiford used to have a bus a week. Rerouteing of a service of North Devon (which trades as Red Bus) and conversion to mini-bus operation now puts a bus through each village every ten minutes. 0 by Michael Clements