TRAIN OF

Page 40

Page 41

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

THOUGHT

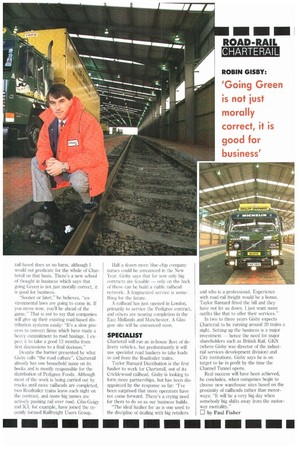

Charterairs Robin Gisby admits he would be foolish to think that moving goods by rail is the answer to everything but it does have advantages over its road-freight counterparts.

• Fact number one: the road network is slowly grinding to a halt whereas the rail _ _ network has a huge amount of spare capacity.

Fact number two: the rise of the Green lobby is pushing business into a more environmentally friendly way of moving goods. Road freight is seen as polluting and intrusive; rail freight is seen as a clean alternative.

Throw in a couple more factors, like the Channel Tunnel and new intertnodal technology, and the equation points firmly in the direction of transferring freight on to the tracks.

However, there are still many difficulties involved in setting up a commercially successful distribution company using rail as a prime mover of goods. Robin Gisby. managing director of newly formed Charterail, is fully aware of the hurdles standing in his way: "Even 10 years ago, I don't think something like Charterail would have been feasible. Now there are certain tidal changes flowing in our favour, but I'd be a fool to think that using rail is the answer to everything."

PHILOSOPHY

Working on that premise, Charterail does not rely solely on the railways. Its philosophy is to use the strengths of both road and rail, The company operates as the prime contractor, taking responsibility for the distribution of goods from the factory or warehouse through to the retailer. It will assemble its own trains of intermodal trailers for trunking by rail to a railhead close to the delivery address, where it will disassemble the trailers and transport them by road to the customer.

British Rail will be employed as a subcontractor with Charterail buying in rail facilities as and when it needs them. BR has already agreed to the arrangement and has taken a minority shareholding in the company.

"From the very start of discussions about Charterail, we agreed that BR should be involved," says Gisby. "That means they are committed to our success because the better we do, the inure money they will make. I would rather see a situation in which a principal subcontractor has an equity rather than continually lighting for co-operation."

FLEXIBILITY

He is keen to emphasise the flexibility of the system: "We are not simply a rail freight user, we are a distributor, and will use whatever mode is best to get goods shifted as fast and as cheaply as possible from A to B. That might be all rail, all road or, more likely, a combination of the two. '"I'he railway's chief disadvantage has always been its inflexibility. With the intermodal technology we are using, we can build small railheads cheaply and quickly. The Cricklewood railhead took six weeks and cost i!300,000, which is chicken-feed compared with traditional terminals."

This ability to build cheap railheads allows Gisby to contemplate establishing dozens of sites around the L.:K, providing rail with some of the flexibility of road transport.

"If you can set up railheads only a few miles from your delivery points," he explains. "you can gain time by avoiding the jams on the motorways and the enforced breaks in the journey required by drivers' hours rules, and still have the flexibility of a door-to-door service. Of course, that means we have to build a hell of a lot of railheads."

Small railheads are possible using the Roadrailer swap-body system which was developed in the US, where it makes 2,000 freight movements a day. Charterail holds the UK licence for Roadrailer. Trains of road trailers are formed by wheeling them into position on a paved railway track and coupled with specially designed railway undercarriage bogies.

Craven Tasker has formed a close relationship with Charterail and the two companies have developed a European version of Roadrailer which is based upon a piggyback-trailer design and can be easily driven on to or reversed off a railway wagon: "Roadrailer gives us the opportunity to take rail haulage back to areas that are no longer adequately served by conventional rail freighting services," says Gisby.

In many cases rail haulage can be faster than road haulage: -With chilled produce, we are looking at one operator running a next-day service out of the Midlands up to Scotland. That's very difficult to do by road. With the Roadrailer, we can run at 145kmili (90mph) and meet the deadlines. Wherever you can no longer make a return trip in a day, because of drivers' hours and congestion, we can find an opening," he says.

Growing environmental concern will help Charterail, but it's not its raison d'etre, says Gisby: "The fact that we are rail-based does us no harm, although I would not predicate for the whole of Charterail on that basis. There's a new school of thought in business which says that going Green is not just morally correct, it is good for business.

"Sooner or later," he believes, "environmental laws are going to come in. If you move now, you'll be ahead of the game." That is not to say that companies will give up their existing road-based distribution systems easily: "It's a slow process to convert firms which have made a heavy commitment to road haulage. I expect it to take a good 12 months from first discussions to a final decision."

Despite the harrier presented by what Gisby calls "the road culture", Charterail already has one household name on its books and is mostly responsible for the distribution of Pedigree Foods. Although most of the work is being carried out by trucks until more railheads are completed, two Roadrailer trains leave each night on the contract, and more big names are actively pushing rail over road. Ciba-Geigy and ICI, for example, have joined the recently formed Railfreight Users Group. Half a dozen more blue-chip company names could he announced in the New Year. Gisby says that for now only big contracts are feasible — only on the back of these can he build a viable railhead network. A fragmented service is something for the future.

A railhead has just opened in London, primarily to service the Pedigree contract, and others are nearing completion in the East Midlands and Manchester. A Glasgow site will be announced soon.

SPECIALIST

Charterail will run an in-house fleet of delivery vehicles, but predominantly it will use specialist road hauliers to take loads to and from the Roadrailer trains.

Taylor Barnard Distribution is the first haulier to work for Charterail, out of its Cricklewood railhead. Gisby is looking to form more partnerships, hut has been disappointed by the response so far: "I've been surprised that more operators have not come forward. There's a crying need for them to do so as our business builds.

"The ideal haulier for us is one used to the discipline of dealing with big retailers and who is a professional. Experience with road-rail freight would be a bonus. Taylor Barnard fitted the bill and they have not let us down. 1 just want more outfits like that to offer their services."

In two to three years Gisby expects Charterail to be running around 20 trains a night. Setting up the business is a major investment hence the need for major shareholders such as British Rail, GKN (where Gisby was director of the industrial services development division) and City institutions. Gisby says he is on target to be in profit by the time the Channel Tunnel opens.

Real success will have been achieved, he concludes, when companies begin to choose new warehouse sites based on the proximity of railheads rather than motorways: "It will be a very big day when somebody big shifts away from the motorway mentality."

by Paul Fisher