Power and Efficiency in Bristol Eight-wheeler

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

Page 41

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By Laurence J. Cotton, M.I.R.T.E. IF the Bristol eight-wheeled chassis, at present built solely for British Road Services, was made available on the open market, it would provide severe competition to manufacturers of similar models. It is produced at a cost which I am assured is comparable with that of any other eight-wheeler, and its build is exceptionally sturdy without being unduly heavy.

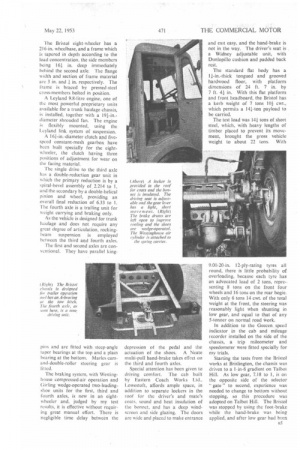

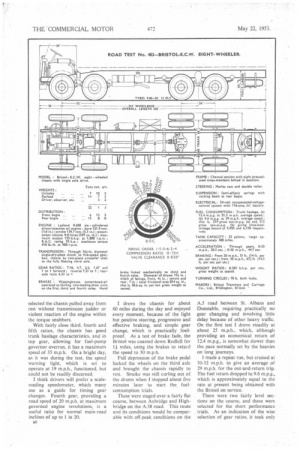

Because it will be operated only in Britain, the Bristol goods chassis has a single-axle drive, which is instrumental in reducing transmission losses, thereby improving perform ance and economy. , The Bristol eight-whecler has a 2I6-in. wheelbase, and a frame which is tapered in depth according to the load concentration, the side members being 161 in. deep immediately behind the second axle. The flange width and section of frame material are 3 in. and .1 in. respectively. The frame is braced by pressed-steel cross-members bolted in position.

A Leyland 9.8-litre engine, one of the most powerful proprietary units available fbr a trunk haulage chassis, is installed, together with a l9.-in.diameter shrouded fan. The engine is flexibly mounted, using the Leyland link system of suspension.

A 16f-in.-diameter clutch and fivespeed constant-mesh gearbox have been built specially for the eightwheeler, the clutch having three positions of adjustment for wear on the facing material.

The single drive to the third axle has a double-reduction gear unit in which the primary reduction is by a spiralsbevel assembly of 2.214 to 1, and the secondary by a double-helical pinion and wheel, providing an overall final reduction of 6.33 to 1. The fourth axle is a trailing unit for weight carrying and braking only.

As the vehicle is designed for trunk haulage and does not require any great degree of articulation, rockingbeam suspension is employed between the third and fourth axles.

The first and second axles are conventional. They have parallel k pins and are fitted with steep-angle taper bearings at the top and a plain bearing at the bottom. Marles camand-double-roller steering gear is fitted.

The braking system, with Westinghouse compressed-air operation and Girling wedge-operated two-leadingshoe units for the first, third and fourth axles, is new in an eightwheeler and, judged by my test results, it is effective without requiring great manual effort. There is negligible time delay between the depression of the pedal and the actuation of the shoes. A Neate multi-pull hand-brake takes effect on the third and fourth axles.

Special attention has been given to driving comfort. The cab built by Eastern Coach Works Ltd.. Lowestoft, affords ample space, in addition to separate lockers in the roof for the driver's and mate's coats, sound and heat insulation of the bonnet, and has a deep windscreen and side glazing. The doors are wide and placed to make entrance and exit easy, and the hand-brake is not in the way. The driver's seat is a Widney adjustable unit, with Dunlopillo cushion and padded back rest.

The standard flat body has a I -in.-thick tongued and grooved hardwood floor, with platform dimensions of 24 ft. 7 in. by 7 ft. 41 in. With this flat platform and front headboard, the Bristol has a kerb weight of 7 tons l0 cwt., which permits a 14-ton payload to be carried.

The test load was 141 tons of sheet steel, which, with heavy lengths of timber placed to prevent its movement, brought the gross vehicle weight to about 22 tons. With 9.00-20-in. 12-ply-rating tyres all round, there is little probability of overloading, because each tyre has an advocated load of 2 tons, representing 8 tons on the front four wheels and 16 tons on the rear bogie. With only 6 tons 14 cwt. of the total weight at the front, the steering was reasonably light when shunting in low gear, and equal to that of any 5-tonner on normal road Work.

In addition to the Geecen , speed indicator in the cab and mileage recorder installed on the side of the chassis, a trip mileometer and speedometer were fitted specially for rny trials.

Starting the tests from the Bristol works at Brislington, the chassis was driven to a 1-in-6 gradient on Talbot Hill. As low gear, 7.18 to 1, is on the opposite side of the selector " gate " to second, experience was needed to change to bottom without stopping, so this procedure was adopted on Talbot Hill. The Bristol was stopped by using the foot-brake while the hand-brake was being applied, and after low gear had been. selected the chassis pulled away from rest without transmission judder or violent reaction of the engine within the torque snubbers.

With fairly close third, fourth and fifth ratios, the chassis has good trunk haulage characteristics, and in top gear, allowing for fuel-pump governor overrun, it has a maximum speed of 35 m.p.h. On a bright day, as it was during the test, the speed warning light, which is set to operate at 19 m.p.h., functioned, but could not be readily discerned.

I think drivers will prefer a scalereading speedometer, which many use as a guide for timing gear changes. Fourth gear, providing a road speed of 20 m.p.h. at maximum governed engine revolutions, is a useful ratio for normal main-road inclines of up to 1 in 20.

Bfi

I drove the chassis for about 60 miles during the day and enjoyed every moment, because of the light but positive steering, progressive and effective braking, and simple gear change, which is practically foolproof. As a test of brake fade, the Bristol was coasted down Redhill for 1 I miles, using the brakes to retard the speed to 30 m.p.h.

Full depression of the brake pedal locked the wheels on the third axle and brought the chassis rapidly to rest. Smoke was still curling out of the drums when I stopped about five minutes later to start the fuelconsumption trials.

These were staged over a fairly flat course, between Axbridge and High. bridge on the A.38 road. This route and its conditions would be comparable with off-peak conditions on the A.5 road between St. Albans and Dunstable, requiring practically no gear changing and involving little delay because of other heavy traffic. On the first test I drove steadily at about 25 m.p.h., which, although providing an economical return of 12.4 m.p.g., is somewhat slower than the pace normally set by the heavies on long journeys.

I made a repeat run, but cruised at 30-32 m.p.h. to give an average of 29 m.p.h. for the out-and-return trip. The fuel return dropped to 9.6 m.p.g., which is approximately equal to the rate at present being obtained with the Bristol on service.

There were two fairly level sections on the course, and these were selected for the short performance trials. As an indication of the wise selection of gear ratios, it took only 20 sec. to reach 20 m.p.h. from rest, and a further 25 sec. to reach 30 m.p.h. in top gear.

The brake tests were made with two markers, my own equipment being connected to the brake pedal and the second operated by a brake shoe on the fourth axle. This enabled a check to be made on the time delay of the air system.

From 20 m.p.h. the true braking distance was 31 ft, and with the second marker indicating a 28-ft. stop. the time delay worked out to sec.

There was considerable wheel locking on the third axle when stopping in an emergency from 30 m.p.h., but the high standard of efficiency was maintained, the average stopping distance being 67i ft. From habit, I stamped hard on the brake pedal when making these tests, but a 75-lb. effort would have been sufficient to obtain the same results.

As a test of manceuvrability, drove the chassis through the narrow streets of Axbridge and turned at the ancient market cross in Cheddar.

The chassis handled well, and with no blind spots, I drove without apprehension through _ spaces with about 3 in. to spare on each side.

Temperature tests were made when reclimbing Redhill, and there were no indications of overheating from the engine or transmission. As a finale, I staged a stop-start test on Redcatch Hill, where the gradient is I in 5}. Despite slight clutch slip, the Bristol accomplished this severe test, and I reluctantly parted company with it when I returned it to the Bristol 'works.