TRANSPORT AND T TEXTILE INDUSTRY.

Page 16

Page 17

Page 18

Page 19

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

The Extraordinarily Complete F Vehicles in the Transport of 11 Lyed by Steam Wagons and Motor in the Textile Industtial Centres.

IT HAS been estimated that the volume of industrial motor traffic, including, of course, passenger motor traffic, has increased over the pre-war level by 65 per cent. This is really a. remarkable figure, and when it is taken into consideration that the increase represents an average figure over the whole country, including agricultural counties and thinly populated districts where the increase in motor traffic has been very small, some idea will be gained of the high increase which must have taken place in the industrial centres.

With the exception of one or two special branches of mechanical road transport, however, this increase cannot be looked upon as an entirely normal develop ment. The war brought about a number of inAuences which have, directly and indirectly, had their effect upon the roacrtranspart organizations of the country. in the first place, the war constituted a powerful stimulus, in that the demand for rapid development and independent door-to-door transport assumed such proportions as had never before been experienced. Again, the almost complete monopoly of the railways for the carriage of war material opened many additional fields in which it was found. that mechanical road transport could operate successfully. Moreover, during the five war years these circumstances continued, in a greater or lesser degree, to be favourable to direct road transport, with the inevitable result that there was a boom" in the industry which continued also for two years after the war. Following the boom naturally came the reaction or slump, which, as a matter of fact, is, at the present moment of writing, still affecting many Lancashire firms and haulage organiza=: tions.

The release of the railways from war work might have been expected to deal a: very serieus blow at the innumerable-road transport companies which had been formed throughout the. country, in spite of the undoubted advantages which the latter offered in the matter of door-to-door collection and delivery of goods. This, probably, would have been the case had the railways been able to return to work offering the industrialists their services at something like reasonable rates. The charges which the railways imposed upon the carriage of merchandise, however, went far . tc■ minimize the effect of the blow which might otherwise have been felt by the road haulage companies. It is not proposed here to enumerate the many difficulties which have been experienced by—and this without exaggeration— every individual industrialist in the country on account. of the charges levied by the railways and the independent attitude adopted by these companies in the matter of the carriage of goods, but it will be realized that, in so doing, the railway authorities forged an exceedingly strong link in the chain of efficient motor services which are in operation to-day.

"Textiles" Demand Road Transport.

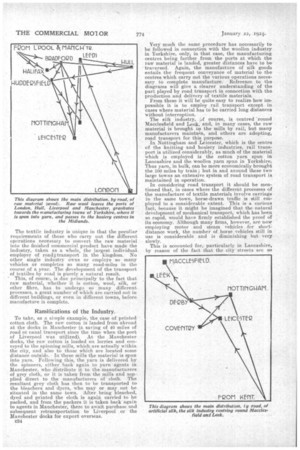

One of the exceptions referred -to in a preceding paragraph, with regard to the.present state of road transport not being strictly a normal development, is that of the application of motor haulage to the -textile industry. The textile industry is unique in that the peculiar requirements of those who carry out the different operations necessary to convert the raw material into the finished commercial product have made the industry, taken as a whole, the largest individual. employer of roadVransport in the kingdom. No other single industry owns or employs so many vehicles or completes so many road-miles in the course of a year The development of the transport of textiles by road is purely a natural result.

' This, of course, is due principally to the fact that raw material, whether it is cotton, wool, silk, or other fibre, has to undergo so many different processes, a great number of which aiv carried out in different buildings, or even in different towns, before manufacture is complete.

Ramifications of the Industry.

To take, as a simple example, the case of printed cotton cloth. The raw cotton is landed from abroad at the docks in Manchester (a saving of 40 miles of road or canal transport since the time when the port of Liverpool was utilized). At the Manchester docks, the raw cotton is loaded on lorries and conveyed to the spinning mills, which-are actually within the city, and also to those which are located some distance outside. • In these mills the material is spun into yarn. Following this, the yarn is delivered by the spinners, either back again to yarn agents in Manchester, who distribute it to the manufacturers of grey cloth, or it is taken from the mills and supplied direct to the manufacturers of cloth. The resultant grey cloth has then to be transported to the bleachers and dyers, who may or may not be situated in the same town. After being bleached, dyed and printed the cloth is again carried to be packed, and from the packers it is taken back again to agents in Manchester, there to await purchase and subsequent retransportation to Liverpool or the Manchester docks for export overseas.

C34

Very much the same procedure has necessarily to be followed in connection with the woollen industry in Yorkshire, only, in that case, the manufacturing centres being further from the ports at which the raw material is landed, greater distances have to be traversed. Again, the manufacture of silk goods entails the frequent conveyance of material to the centres which carry out the various operations necessary to complete manufacture. Reference to the diagrams will give a clearer understanding of the part played by road transport in connection with the production and delivery of textile materials.

From these it will be quite easy to realize how impossible it is to employ rail transport except in cases where material has to be carried long distances without interruption, •

The silk industry. ;if course, is centred 'round Macclesfield and Leek; and, in many cases, the raw material is brought to the mills by rail, but many manufacturers maintaj-n, and others are adopting, road transport for this purpose.

In Nottingham and Leicester, which is the centre of the knitting and hosiery industries, rail transport is utilized considerably, as much of the material which is employed is the cotton yarn spun in Lancashire and the woollen yarn spun in Yorkshire Thus yarn, in bulk, can be more economically brought the 100 miles by train ; but in and around these two large towns an extensive system of road transport is maintained in operation.

In considering road transport it should be mentioned that, in cases where the different processes of the manufacture of textile materials involve carriage in the same town, horse-drawn traffic is still employed to a considerable extent. This is a curious fact, because it might be imagined that the natural development of mechanical transport, which has been so rapid, would have firmly established the proof of its economy. Although many firms, however, are now employing motor and steam vehicles for shortdistance work, the number of horse vehicles still in use is considerable and is diminishing but very slowly. This is accounted for; particularly in Lancashire, by reason of the fact that the city 'streets are so WA R R I NGTO N 704000

congested that, for short-distance work, the motor vehicle cannot give effeet• to its superior speed and consequent greater tonnage return.

The driver of a •three-ton petrol lorry, questioned in. Manchester recently, stated that, although he could run a full load of raw cotton from the docks at Liverpool to the outskirts at Manchester in well under four hours, it took him an hour to run the last three miles through Manchester.

Trams and horse traffic, of course, are responsible for this. The trams, in the first place, monopolize 50 per cent. of the available road space, and, for the rest, the slowest vehicle, which is the horse-drawn wagon, more or less governs the pace of traffic on the remaining portion of the highway.

It is impossible to do away with such a vast system of tramways as exists in Lancashire, but while they remain in busy thoroughfares the efficiency of the motor vehicle will continue to he reduced, and so, as a result, there will remain many industrialists who, quite rightly, wilL not go to the expense of employing motor vehicles which show so little superiority over the horsed wagon. Thus is development held hack.

Realizing the efficiency of the motor lorry over routes which will allow the vehicle to give effect to its speed, one particular Manchester organization hats established, outside the city, depots to which the lorries may bring goods from other manufacturing towns and there transfer them, on flats, by means of electric cranes, to horse-drawn vehicles which are able to convey the loads over the last shert portion of the journey through the city.

By this means the motor vehicles are freed from the time-consuming delays which travel through the city involves, but, on the other hand, the proportion of horse-drawn vehicles in the city is thus inereaeed, and, so, is adding to the problems which beset the traffic authOrities.

The traffic problem in Lancashire is, indeed, assuming very grave proportions. The main streets of almost all its manufacturing towns are narrow, tortuous and intersected by innumerable and narrower by-streets. In these by-streets it so happens that a great number of cloth and yarn warehouses are situated, especially in Manchester itself ; traffic to and from these places is extremely heavy, so that the conditions brought about by many large vehicles turning from main roads, already narrow and well-nigh monopolized by hosts of trams, into still more tortuous and congested alleyways, can be better imagined than described.

Motor vehicles manage this difficult operation as expeditiously as could be expected in the circurn. stances, but when a string of four or five heavily laden horse-drawn vehicles draws out in the main road, conditions become appalling. In the

OUTHPORT LIVERPOOL

STHELENea

33

WIGAN

1,092,790

first place, policemen on point duty hold up all the. traffic to enable the crawling horse vans to etnerge into the main artery at all. By the time these oldfashioned floats are all out in the main road there is a congestion of six or eight teams holding the centre of the road, whilst behind these, dozens of light motor VaPS, lorries and all kinds of other traffic are drawn up in ,a mass. When, eventually, the policeman gives his general signal to " carry on,' there are the eight trams to move first. The motor traffic has to wait until these are at/ away before it can move, because, of course, no lorry can overtake the trams on the near side on account of the fact that there are the horse vehicles, moving at about three miles an hour, completely

filling the road between t h e trams • and the kerb.

It is equally impossible f o r the lorries to swing out and pass the trams on the off side, as similar crowded conditions obtain on that side of the street. The waiting motor traffic, t h e needs, must follow the 10.1

7,538,145 trams. S o o n, however, a further complication arises. The 71. ASHTON horse vans continue at their ewe) three miles an OLDHA M 17,384,07 5,393,930hour, but the -0CPC PO PT

the front tram, reaches a stopping-pleee. Now, t h e stoppingplaces on the Lancashire tramway systems are as important as the stations an the London " Underground," They are not places for a mere pause, but points where a full pull-up is made while twenty or thirty people alight and, this finished; about the same number, or more get aboard.

• Then ensues chaos indeed. Six or eight statiohary trams in line, slow-Moving horse vehicles between them and the kerb, a swarm of alighting and boarding passengers dodging the horses and, finally, a heterogeneous collection of traffic of all sorts waiting in the rear.

The complaints regarding this condition of things, which have been lodged in official quarters, are many. Suggested remedies are equally numerous, but no real attempt at improvement seems to have been undertaken. A few months ago, the Manchester Corporation did go very seriously into the question of partly doing away with the cause of a great part of the trouble—the trams. Officialdom said "if you can provide an alternative means of transport which will prove as efficient as the electric trams and at the same time be no more expensive —," but, to put it shortly, nothing was found to fulfil these demands absolutely, so nothing was done which would materially improve the present conditions. Such official attitude, however, is opeil to wide criticism. The writer is not prepared to state whether the municipal body would be justified in inaugurating more modern transport at the expense of the ratepayer, but to the looker-on it certainly seems that progress is relentlessly impeded: