Behind the

Page 48

Page 49

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Commercial Motor joined Paul Selway Transport travelling with a German charity convoy to Romania. Having set off from Munich, we have just crossed the Hungarian border...

• Our first stop after the Hungarian border was at a motel where we struck a deal for 220 litres of diesel for 100 marks on the black market. In Eastern Europe the dollar and the Deutschmark are universal currency. Erich Frisch, convoy leader, lectured us not to open our doors in Romania or feed the beggars, "They are in a transitional period and it doesn't help them," he said.

We passed a Hungarian-built lfa truck struggling up a hill on the motorway. Although Hungarocamion, the state haulier, is a big buyer of Western trucks, locals still have to depend on the cheaper Hungarian versions. "How could you ever run a haulage company in England or anywhere else with these?" Steve Sims of Paul Selway Transport asked.

Outside Budapest we hired a taxi to pilot us through the city. This annoyed Sims, who drives through Budapest regularly and knows the streets. Erich, however, was keen to stay in convoy, with his Trooper leading and Steve's relatively fast truck second or third last. Budapest is a busy city, looking a bit like a shabbier version of Paris 30 years ago. It took us over an hour to cross; a bypass is still a pipedream.

At 6pm we stopped in a layby alongside two Russians in their Mazes. "They can't be party men," said Sims, "party men drive Volvos." He explained that in Russia, an international driver is one of the best professions to be in, as they get the chance to buy Western goods and smuggle them back to sell on the black market.

We reached the Romanian border near Ordea, four hours later. We were held up there for only an hour, despite Sims' fears that getting into Romania with a convoy might be a problem. Guards were slipped packets of cigarettes to speed things up; one of Sims' tactics was to address officers by the next highest rank. When the soldier replied that he was just, say, a captain, Steve's retort was: "Ah, but you should be a major."

One of the jokes doing the rounds at the height of the flood of East Germans into the West last summer was: "Would the last one out please turn out the lights." In Ordea, the first town over the border, it looked as if they already had.

At 10.30pm nothing moved. Years of mismanagement by the Communists has left the country without enough power to light the streets, and only the odd 60 watt bulb brightened living rooms in grim concrete apartment blocks. Fog and drizzle added to the Orwellian scene.

As we moved on to the winding roads on the foothills of the Carpathians, the convoy slowed. The less-experienced drivers tended to use their brakes too much when going downhill, and this caused a minor panic when the smell of burning rubber suggested that some linings might have gone. We reached our hotel in Cluj, tired out, at 4am. Like many Ceausescu-inspired buildings, the hotel, Cluj's best, looked impressive. Inside, however, the bathrooms had no plugs or toilet paper, the televisions in the rooms did not work and, despite an abundance of staff, the beds were rarely made.

LOCAL RADIO

The next day Erich gave interviews to local radio and called contacts in Romania to arrange drops. For the rest of us there was nothing to do but sit in the hotel.

The following morning, Saturday, we set off at 7.30am and arrived at the first mountain village where Erich had made contact at 8.45am, some 20km from Cluj. The rest of the convoy was sent ahead as Steve's truck was unloaded. As soon as we stopped, peasant women in black shawls jostled to see what was happening.

For a few minutes, everything went well as each family took its box of supplies. Soon, however, passing cars and truckers pulled up and began to push forward for packages. Erich was unwilling to give them food and the atmosphere became nasty. Helmut was told to drive away but, flustered, he stalled repeatedly. Finally, Steve jumped into the cab and we moved off with the trailer doors open and Erich with two interpreters still inside.

Erich later used the incident to impress upon us why we had to be ready to get away immediately if such situations arose again. Our next stop was a hospital, mainly for children, in the town of Turda. Again, as soon as we stopped a crowd gathered. Erich and Anna talked to hospital officials about what supplies they needed.

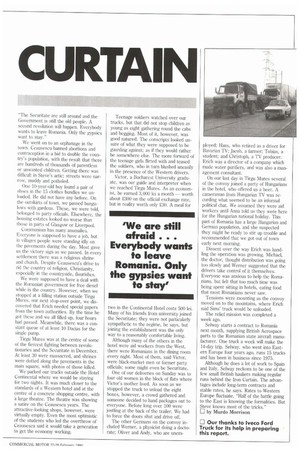

Inside, the hospital did not look crowded, but it did seem pitifully understocked. A woman of 60 said things had improved since the overthrow of Ceausescu: people could now buy a loaf of bread a day, but sugar and most other items were unavailable. "We are still afraid," she said. "The Securitate are still around and the Government is still the old people. A second revolution will happen. Everybody wants to leave Romania. Only the gypsies want to stay."

We went on to an orphanage in the town. Ceausescu banned abortions and contraception in a bid to double the country's population, with the result that there are hundreds of thousands of parentless or unwanted children. Getting there was difficult in Steve's artic; streets were narrow, muddy and potholed.

One 10-year-old boy found a pair of shoes in the 15 clothes bundles we unloaded. He did not have any before. On the outskirts of town, we passed bungalows with gardens. These, we were told, belonged to party officials. Elsewhere, the housing estates looked no worse than those in parts of Glasgow or Liverpool.

Communism has many anomalies. Everyone is supposed to have a job, but in villages people were standing idly on the pavements during the day. Most gave us the victory sign as we passed. In every settlement there was a religious shrine and church. Despite Ceausescu's drive to rid the country of religion, Christianity, especially in the countryside, flourishes.

We were supposed to have a deal with the Romanian government for free diesel while in the country. However, when we stopped at a filling station outside Tirgu Mures, our next stop-over point, we discovered that Erich needed special papers from the town authorities. By the time he got these and we all filled up, four hours had passed. Meanwhile, there was a constant queue of at least 10 Dacias for the single pump.

Tirgu Mures was at the centre of some of the fiercest fighting between revolutionaries and the Securitate in December. At least 30 were massacred, and shrines were dotted along the pavements in the main square, with photos of those killed.

We parked our trucks outside the Hotel Continental where we would be staying for two nights. It was much closer to the standards of a Western hotel and at the centre of a concrete shopping centre, with a large theatre. The theatre was showing a satire on the Ceausescu years. The attractive-looking shops, however, were virtually empty. Even the most optimistic of the students who led the overthrow of Ceausescu said it would take a generation to get the economy working. Teenage soldiers watched over our trucks, but that did not stop children as young as eight gathering round the cabs and begging. Most of it, however, was good natured. The conscripts looked unsure of what they were supposed to be guarding against; as if they would rather be somewhere else. 'Ile more forward of the teenage girls flirted with and teased the soldiers, who in turn blushed uneasily in the presence of the Western drivers.

Victor, a Bucharest University graduate, was our guide and interpreter when we reached Tirgu Mures. As an economist, he earned 3,000 lei a month — worth about £300 on the official exchange rate, but in reality worth only f..'30. A meal for two in the Continental Hotel costs 500 lei. Many of his friends from university joined the Securitate; they were not particularly sympathetic to the regime, he says, but joining the establishment was the only way to a reasonably comfortable living.

Although many of the others in the hotel were aid workers from the West, there were Romanians in the dining room every night. Most of them, said Victor, were black-market men or former party officials; some might even be Securitate.

One of our deliveries on Sunday was to four old women in the block of flats where Victor's mother lived. As soon as we stopped the truck to unload the eight boxes, however, a crowd gathered and someone decided to hand packages out to everyone. Before long over 100 were jostling at the back of the trailer. We had to force the doors shut and drive off.

The other Germans on the convoy included Werner, a physicist doing a doctorate; Oliver and Andy, who are unem

ployed; Hans, who retired as a driver for Bavarian TV; Jacob, a farmer; Tobias, a student; and Christoph, a TV producer. Erich was a director of a company which made water purifiers, and was also a management consultant.

On our last day in Tirgu Mures several of the convoy joined a party of Hungarians in the hotel, who offered us a beer. A cameraman from Hungarian Tv was recording what seemed to be an informal political chat. We assumed they were aid workers until Anna told us they were here for the Hungarian national holiday. This part of Romania has a large Hungarian and German population, and she suspected they might be ready to stir up trouble and recommended that we got out of town early next morning.

Dissent over the way Erich was handling the operation was growing. Michael, the doctor, thought distribution was going too slowly and Werner suggested that the drivers take control of it themselves. Everyone was anxious to help the Romanians, but felt that too much time was being spent sitting in hotels, eating food that most Romanians never saw.

Tensions were mounting as the convoy moved on to the mountains, where Erich said Sims' truck would be unloaded.

The relief mission was completed a week ago.

Selway starts a contract to Romania next month, supplying British Aerospace parts to the Romanian state aircraft manufacturer. One truck a week will make the 14-day trip. Selway, who went into Eastern Europe four years ago, runs 15 trucks and has been in business since 1975.

Although he does a lot of work to Spain and Italy, Selway reckons to be one of the few small British hauliers making regular runs behind the Iron Curtain. The advantages include long-term contracts and stable rates, he says. Rates to Western Europe fluctuate. "Half of the battle going to the East is knowing the formalities. But Steve knows most of the tricks."

0 by Murdo Morrison