SLEEK, SAFE

Page 54

Page 55

Page 56

Page 57

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

SURE-FOOTED

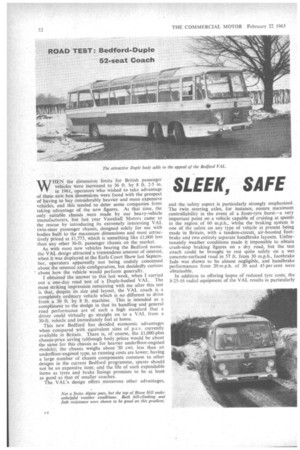

WHEN the dimension limits for British passenger vehicles were increased to 36 ft. by 8 ft. 2-5 in. in 1961, operators who wished to take advantage of these new box dimensions were faced with the prospect of having to buy considerably heavier and more expensive vehicles, and this tended to deter some companies from taking advantage of the new figures. At that time, the only suitable chassis were made by our heavy-vehicle manufacturers, but last year Vauxhall Motors came to the rescue by introducing its extremely interesting VAL twin-steer passenger chassis, designed solely for use with bodies built to the maximum dimensions and most attractively priced at £1,775, which is something like £1,000 less than any other 36-ft. passenger chassis on the market.

As with most new vehicles bearing the Bedford name, the VAL design attracted a tremendous amount of interest, when it was displayed at the Earls Court Show last September, operators apparently not being unduly concerned about the unusual axle configuration, but decidedly curious • about how the vehicle would perform generally.

I obtained the answer to this last week, when I carried out a one-day road test of a Duple-bodied VAL. The most striking impression remaining with me after this test is that, despite its size and layout, the VAL coach is a completely ordinary vehicle which is no different to drive from a 30 ft. by 8 ft. machine. This is intended as a compliment to the design in that its handling and general road performance are of such a high standard that a driver could virtually go straight on to a VAL from a 30-ft. vehicle and immediately feel at home.

This new Bedford has decided economic advantages when compared with equivalent sizes of p.s.v. currently available in Britain. There is, of course, the £1,000-plus chassis-price saving (although body prices would be about the same for this chassis as for heavier underfloor-engirted

models); the chassis weighs about .30 cwt. less than an

underfloor-engined type, so running costs are lower; having a large number of chassis components common to other designs in the current Bedford programme, spares should not be an expensive item; and the life of such expendable items as tyres and brake linings promises to be at least as good as that of smaller coaches. The VAL's design offers numerous other advantages,

and the safety aspect is particularly strongly emphasized. The twin steering axles, for instance, ensure maximum controllability in the event of a front-tyre burst—a very important point on a vehicle capable of cruising at speeds in the region of 60 m.p.h., whilst the braking system is one of the safest on any type of vehicle at present being made in Britain, with a tandem-circuit, air-boosted footbrake and two entirely separate handbrake layouts. Unfortunately Weather conditions made it impossible to obtain crash-stop braking figures on a dry road, but the test coach could be brought to rest quite safely on a wet concrete-surfaced road in 57 ft. from 30 m.p.h., footbrake fade was shown to be almost negligible, and handbrake performances from 20 m.p.h. of 30 and 45 per cent were obtainable.

In addition to offering hopes of reduced tyre costs, the 8-25-16 radial equipment of the VAL results in particularly good roadholding; the coach can be taken into roundabouts at speeds which many private motorists would not consider feasible, and with the utmost confidence and the minimum of roll. So far as roll stability is concerned the suspension layout enhances the effect of the low centre of gravity given by the small wheels and tyres, and when cruising along straight pieces of road the suspension again proves its worth, although small bumps (such as the dividing strips found on concrete road surfaces, and cat's eyes) could be felt quite clearly when sitting in certain parts of the body.

Similarly, because of the body length, passengers will be aware of a greater degree of pitching than is noticeable in a 30-ft. coach, but when the vehicle is fully laden this should not be sufficient to cause nausea. I am not a good coach passenger by any stretch of the imagination, and although a ride some months ago in one of the rear seats of an almost empty VAL caused me to feel a little uneasy, I was quite happy with last week's test vehicle, which was carrying the equivalent of 56 passengers (3.5 tons).

The Bedford-Duple vehicle supplied for me to test was the coach actually exhibited on the Duple stand at last year's Earls Court Show. The basic price of the Vega Major body is £3,625, giving a total. basic nice for the complete vehicle of £5,400. This body is, to ny mind, the most attractively styled yet to have been iffered for the VAL chassis, the vehicle having a well)alanced appearance and smart but uncluttered lines. The )ody had 52 seats, at 2-ft. 4-in, pitch, whilst there are ilternative layouts for 49 or 50 seats, giving a welcome mount of additional room between some of the seats. The )ody is of composite construction, with metal-reinforced iardwood framing and most of the exterior panels in duminium alloy, although some of the front and rear ianeIs are plastics mouldings and the rear corner panels ire of Zintec.

It had a single inward-opening passenger door ahead of he nearside front wheel—the chassis frame having been lesigned specifically, for this door location. As originally ntroduced, the chassis had its fuel tank behind the offside ear wheel, but by moving this to ahead of the wheel ind by positioning the spare-wheel carrier in front of the Learside wheel it has proved possible to increase the rear uggage locker capacity from 76 to 105 Cu. ft. whilst the ,earside locker's capacity has been cut from 38 to 33 Cuft. —a net increase of 24 Cu. ft. A 45-gal. tank is now used instead of the original 26-gal. tank.

Because of the small wheels the body floor is flat throughout the length of the vehicle, the laden floor height being 3 ft. 1.325 in The laden height of the entrance step is 1 ft. 6-125 in., with an intermediate step 11-5 in. higher than this. Although there is obviously not quite so much .room around the entrance area as can be provided with an underfloor-engined chassis, the engine cowl at the extreme front of the vehicle does not provide a detrimental degree of obstruction to passenger movement, particularly when the foremost seat on the nearside is a single one, as in the case of the 50and 52-seat bodies.

The VAL chassis itself is by now too well known to warrant .extensive description in this road-test report, a fully illustrated account of the design having appeared in our September 14, 1962, issue, whilst brief basic details arc given in the data panel which accompanies this report. The only specification options applicable to the VAL concern the rear-axle gearing, the standard final-drive ratio being 5-3 to 1, with options of 4.6 and 5.8 to 1, a further option being a Bedford two-speed axle with air-pressure shift and ratios of 4-86 and 6-63 to I. The test vehicle had the standard axle, which gives a theoretical bottomgear grade-ability of 1 in -3-5 and a maximum speed of approximately 58 m.p.h. (the Leyland engine is governed to 2,600 r.p.m., which is 200 r.p.m. higher than the governed speed of this unit when used in Leyland vehicles).

A change to the standard specification concerns the handbrake mechanism operating the steering-axle brakes. As originally introduced in September, the VAL had a conventional single-pull lever to the left of the driving seat with direct cable connection to the four front brakes. To increase the power of this brake a German StopfixBrernse unit—still to the left of the driving seat—is used now. This incorporates a mechanical spring servo so that although the action of the lever remains single pull, the mechanical-advantage ratio varies from 4 to I at the start of the pull to 16 to I at the finish, the final ratio being mildly augmented by a toggle spring in the linkage. The operating lever for the transmission brake on the nose of the rear axle is as before, being of the pull-up umbrella type.

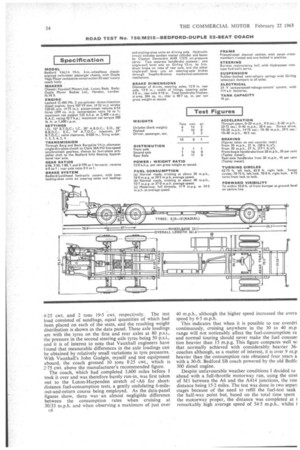

Ready for the road the coach had a kerb weight of 6 tons 4-75 cwt., the loadings on the first, second and rear axles in this condition being 2 tons 11 cwt.. 1 ton 4.25 cwt. and 2 tons 19-5 Cwt. respectively. The test load consisted of sandbags, equal quantities of which had been placed on each of the seats, and the resulting weight distribution is shown in the data panel. These axle loadings are with the tyres on the first and rear axles at 80 p.s.i., the pressure in the second steering axle tyres being 50 p.s.i., and it is of interest to note that Vauxhall engineers have found that measurable differences in the axle loadings can be obtained by relatively small variations in tyre pressures. With Vauxhall's John Gudgin, myself and test equipment aboard, the coach grossed 10 tons 8.25 cwt., which is 2.75 cwt. above the manufacturer's recommended figure.

The coach, which had completed 3,600 miles before I took it over and was therefore barely run-in, was first taken out to the Luton-Harpenden stretch of *A6 for shortdistance fuel-consumption tests, a gently undulating 6-mileout-and-return course being employed. As the data-panel figures show, there was an almost negligible difference between the consumption rates when cruising at 30/33 m.p.h. and when observing a maximum of just over c6 40 m.p.h., although the higher speed increased the avera speed by 6.5 m.p.h.

This indicates that when it is possible to use overdri continuously, cruising anywhere in the 30 to 40 m.p range will not noticeably affect the fuel-consumption ra and normal touring should never make the fuel consum tion heavier than 15 m.p.g. This figure compares well wi that normally achieved with considerably heavier 36coaches although, as a matter of interest, it is over 9 imp heavier than the consumption rate obtained four years a with a 30-ft. Bedford SB coach powered by the old Bedfc 300 diesel engine.

Despite unfavourable weather conditions I decided to ahead with a full-throttle motorway run, using the stret of MI between the A6 and the A414 junctions, the rou distance being 15-2 miles. The test was done in two sepan stages because of the need to refill the fuel-test tank the half-way point but, based on the total time spent the motorway proper, the distance was completed at I remarkably high average speed of 54.5 m.p.h., whilst I

.onsumption rate was equally commendable at 11.9 m.p.g. )n level stretches of the motorway the coach was able o maintain nearly 60 m.p.h., and at no time did the speed en hills drop below 43 m.p.h.

Very good acceleration times were recorded—better hrough the gears, in fact, than those obtained with the lB coach in 1959—but I could not help feeling that the ather large gear-ratio gap between third and fourth was ereventing the acceleration rate from being even better. his gap tended to be a disadvantage also when taking airly sharp gradients. The direct-drive acceleration etween 10 and 40 m.p.h. was satisfactory, but the pickip between 9 and 14 m.p.h. surged a little, indicating hat the rear-axle ratio was a bit high for satisfactory vork in this gear below about 20 m.p.h. Speeds in the :ears were 8, 14, 27, 48 and 58 m.p.h.

Had there been any dry roads in the Luton area, I m quite sure that brake tests would have shown the oach could have stopped in well under 50 ft. from 0 m.p.h., but, as it was, tests had to be conducted on a treaming wet stretch of concrete road, despite which good Ewes were obtained. The rear wheels locked on each ccasion, but stability was not affected and maximum -apIey-meter readings were 72 per cent from 20 m.p.h. and 3 per cent from 30 m.p.h. As shown in the data panel, 0th handbrakes were very powerful, the figure of 45 per ent produced by the transmission brake being achieved rithout wheel locking. In a real emergency it should be ossible to apply both brakes—one after the other, of ourse—in which case probably over 60 per cent would e obtainable.

A reconnaissance by car showed that there was just bout enough room between the banks of snow to get le coach up Bison Hill, so an ascent of this 0-75-mile lope, the average gradient of which is 1 in 10.5, was made e an ambient temperature of 3.5°C (38°F). The climb aok 3 min. 36 sec., of which 1 min. 28 sec. was spent second gear, during which time the road speed did not ill below 11 m.p.h. but during which time also regrettable mission of black smoke was observed. Apart from the rnoke, the climb was a good one, and with the radiator nblanked the coolant temperature rose from 57'C 35°F) to 63°C (146'F), showing the cooling-system apacity to be more than adequate.

The road up the hill was not too slippery, so a fade est was made by coasting the coach down in neutral, olding the speed to below 20 m.p.h. by use of the footrake alone. This is a severe test of fade-resistance haracteristics, but after the 2 min. 42 sec. descent a crash :op at the bottom of the hill produced a Tapley-meter !ading of 64 per cent, showing an efficiency drop of only per cent. There was some smell of hot linings, but none f the drums was smoking, and pedal travel increase was ight.

Returning to the 1-in-6.5 section of the hill, the coach as stopped on this gradient and each of the handbrakes eld it with ease. An attempted second-gear restart failed vough lack of engine power—even when the clutch was lipped viciously, but a bottom-gear get-away was easy.

From the driver's viewpoint the VAL coach is very pleasant to handle, -the slight initial sensation of steering vagueness soon wearing off, although the rather weak castor action proved a bit troublesome on tight corners. The power-steering effect was just right and a great effort saver. For my liking the steering column was too far to the left of the pedals, seat and so forth, but this is purely personal opinion. The gearchange also was not quite 100 per cent, being a bit on the stiff side with rather long and vague travel, though here again after a few miles on the road I tended to forget my original criticisms. The brake pedal has a fully progressive action, and high efforts are required only for emergency purposes.

With a low winter sun I found the Rolevisor-type sun visor to be pitifully small for the size of the windscreen, and this presented serious problems when driving over slippery roads against the setting sun. The visor needs to be at least 9 in. deeper and several inches wider if it is to be of any real value.

The coach is entirely satisfactory from the passengers' angle, other than the closeness of the seats and the slight pitching effect. Although a Show vehicle, I did feel that the finish was not too brilliant in parts of the body, the passenger door being a particularly bad fit, whilst the roof vents created draughts, even when tightly closed. I was surprised also that the four Punkah-type ventilators in each side of the rear of the body could not be turned off. And while on the question of finish, the Bedford TK truck-type steering-wheel--although not in itself unattractive—is a bit crude for a luxury coach.

The engine cowl is a one-piece plastics moulding, covered with moquette and lined with foam-plastics insulation, held in place by wire mesh. The resulting sound insulation is quite good for a front-engined coach and, indeed, passengers at the extreme rear of the body will not find the engine noise irritating, even when running on the governor. In the seats nearer the front, however, the power unit betrays its presence, though not in the form of vibration, the mountings being particularly smooth.

Three spring clips hold the cowl in place, and with the cowl off good access is given to the upper part of the engine, the air cleaner and the reservoir for the powersteering fluid. Being below floor level, the fuel-injection pump and air compressor are not easy to reach, but the lift pump is not so inaccessible. The dynamo tends to be rather out of the way, particularly as two longitudinal heater pipes pass directly above it. and this would complicate fan-belt adjustment also. The complete cowl has to be removed, incidentally, to gain access to the dip stick, which is on the driver's side of the engine. Routine chassis maintenance is greatly reduced by the use of rubber bushes in the suspension, and there are only 13 greasers all told.

All in all, the Bedford VAL design is a very good approach to the problem of producing a chassis suitable for 36-ft-long passenger bodywork at a modest price. It brings the 36-footer within the financial reach of a large number of operators, but its relatively low price does not in any way imply low quality. We can expect to see a lot of these twin-steer vehicles on the roads this summer.