CLIMBING 1 IN 4 1 / 4

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

DN PART-THROTTLE

A New 7-ton Chassis with Perkins High-rating Six-cylindered Oil Engine and Five-speed Ultralow Gearbox has Excellent Hill-climbing Performance, Coupled with Economy in Trunk Haulage

By 1. J. COTTON, M.I.R.T.E.

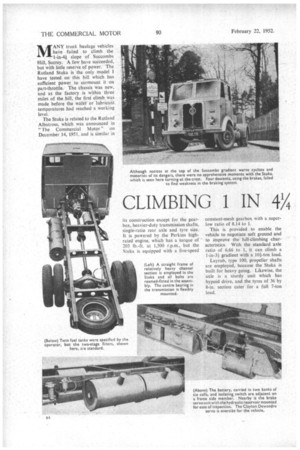

MANY trunk haulage vehicles have failed to climb the 1-in-4i slope of Succombs Hill, Surrey. A few have succeeded, but with little reserve of power. The Rutland Stuka is the only model 1 have tested on this hill which has sufficient power to surmount it on part-throttle. The chassis was new, and as the factory is within three miles of the hill, the first climb was made before the water or lubricant temperatures had reached a working level.

The Stuka is related to the Rutland Albatross, which was announced in "The Commercial Motor" on December 14, 1951, and is similar in its construction except for the gearbox, heavier-duty transmission shafts, single-ratio rear axle and tyre size. It is powered by the Perkins highrated engine, which has a torque of 203 lb.-ft. at 1,500 r.p.m., but the Stuka is equipped with a five-speed constant-mesh gearbox with a superlow ratio of 8.14 to 1.

This is provided to enable the vehicle to negotiate soft ground and to improve the hill-climbing characteristics. With the standard axle ratio of 6.66 to I, it can climb a 1-in-3 gradient with a 10i-ton load.

Layrub, type 100, propeller shafts are employed, because the Stuka is built for heavy going. Likewise, the axle is a sturdy unit which has hypoid drive, and the tyres of 36 by 8-in. section cater for a full 7-ton load. The frame is drilled, reamed and assembled in the Croydon workshops, and such parts as spring brackets, brake and dutch pedals, cross-shafts and the remote-control gear lever are fabricated from materials of generous section. The model tested was one of an order for Jamaica and the operator specified a sturdy front bumper bar. This, I noted, was fabricated from material with a section in keeping with the rest of the chassis assembly.

A large Clayton Dewandre servo, operating the brakes through a Girling hydraulic system and highcent re-lift two-leading-shoe units, provides ample line pressure with light pedal effort. Low-coefficient friction facings are employed and the linkage is arranged to combat the loss of pedal travel. The Neate triple-pull brake lever also ensures that there is ample movement for the high-centre-lift shoes, even with the brake drums well expanded.

As an overseas model, the Stuka provided for test Was equipped with an ant-proof opepe timber composite cab. The cab is jig-built, so that it can be easily knocked down for shipping and should a section become damaged in operation it can be easily exchanged by unskilled labour.

The model tested was the first to be produced, and because it had been completed only half a day before my trials, it had not been on the road except to make brake and other initial adjustments. As the tests included 100 miles of gruelling work, the engine eased off and the venturi-butterfly was reset to give smoother idling. A "slave" set of • tyres was fitted, ml case of damage to the covers during emergency brake applications, and a slight allowance made for inaccuracy in the speedometer, which was caused by running on worn treads.

The chassis and load were weighed at a waterworks which was on the route to Succornbs Hill. The heavy bumper bar and twin fuel tanks specified by the operator increased the unladen weight, which, in standard form, would be approximately 3 tons 3i cwt.

Arriving at. the foot of the climb, I thrust a thermometer into the top tank of the radiator, but the mercury climbed only 40 degrees above the ambient reading of 52 degrees F. An additional observer, rather heavier than normal, boarded the Stuka to witness the hill-climb, and, moving away from rest in second gear, the assault was started.

The engine speed fell rapidly on the 1-in-6 gradient and "crawler gear" was required on the first serious incline. Taking no risks, the driver used second gear when the gradient slackened and then changed to " bottom " before reaching the top

bend, which is the climax of the climb. The engine soared up to maximum speed aiid showed no sign of falling away from the governed range as we , swept round the curve and 'over the brow.

Part-throttle Trials Gaining confidence from this extraordinary exhibition, we made a repeat test with the throttle-.pedal depressed approximately threequarters of its travel, and again the Stuka made the grade without difficulty.

A stop-start test on the 1-in-4i section with• three-quarters throttle faded, but several were successfully completed at full throttle. The ease with which the vehicle pulled away with its massive concrete-block load was indeed impressive.

The driver was completely unconawned, and had full confidence in the braking system on the steep gradient, which also has a steep camber and sharp bend, tending to throw a large proportion of the weight to one corner of the chassis. A fourth climb was made to determine the maximum running temperatures, which were 134 degrees F. for the top water tank and 152 degrees F. for the engine oil Practically Fade-proof The brakes were used on all descents and at the end of the hill tests, a Tapley reading of 58 per cent. was recorded on level ground with an emergency application of the pedal. The drums at this stage were showing signs of heat, but as subsequent readings of 64-68 per cent. were obtained in trials with cold drums, the fade characteristics of the friction material were good.

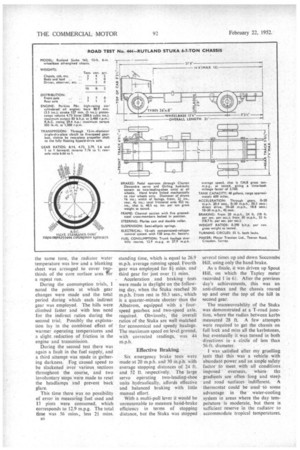

Then followed a 2I-mile-out-andreturn consumption trial, which was marred by a leak through a fuel tap, lending to give inflated results. At

the same time, the radiator water temperature was low and a blanking sheet was arranged to cover tvwthirds of the core surface area ror a repeat run.

During the consumption trials, 1 noted the points at which gear changes were made and the total period during which each indirect gear was employed. The hills were climbed fatter and with less need for the indirect ratios during the second trial. Possibly the explanation lay in the combined effect of warmer operating temperatures and a slight reduction of friction in the engine and transmission.

During the second test there was again a fault in the fuel supply, and a third attempt was made in gathering darkness. Fog caused speed to be slackened over various sections throughout the course, and two involuntary stops were made to reset the headlamps and prevent back glare.

This time there was no possibility of error in measuring fuel Used and 13 pints were consumed, which corresponds to 12.9 m.p.g. The total time was 56 mins., less 24 mins.

standing time, which is equal to 26.9 m.p.h. average running speed. Fourth gear was employed for 81 mins. and third gear for just over 14 mins.

Acceleration' and braking tests were made in daylight on the following day, when the Stuka reached 30 m.p.h. from rest in 50.3 secs., which is a quarter-minute shorter than the Albatross, equipped with a fourspeed gearbox and two-speed axle, required. Obviously, the overall ratios of the Stuka are well matched for economical and speedy haulage. The maximum speed on level ground, with corrected readings, was 44 m.p.h.

Effective Braking

Six emergency brake tests were made at 20 m.p.h. and 30 M.p.h. with average stopping distances of 24 ft. and 52 ft. respectively. The large servo operating two-leading-shoe units hydraulically, affords effective and balanced braking with little manual effort.

With a multi-pull lever it would be unreasonable to measure hand-brake efficiency in terms of stopping distance, but the Stuka was stopped several times up and down Succombs Hill, using only the hand brake.

As 'a finale, it was driven up Spout Hill, on which the Tapley meter recorded 1 in 6. After the previous day's achievements, this was an anti-climax and the chassis roared up and over the top of the hill in second gear.

The manceuvrability of the Stuka was demonstrated at a T-road junction, where the radius between kerbs measured 28 ft. A few attempts were required to get the chassis on full lock and miss all the kerbstones, but eventually -it was turned in both directions in. a circle . of less than

56-ft. diameter. .

1 was satisfied after thy gruelling tests that this was a vehicle with abundant power and an ample safety factor Co meet with all conditions imposed overseas. where the gradients are often long and steep and road surfaces. indifferent. A thermostat could be used • to some advantage in the water-cooling system in areas where the day temperature is moderate, but there is sufficient reserve in the radiator to accommodate tropical temperatures.