thu 1.1'.1f) II f)11

Page 62

Page 63

Page 64

Page 65

Page 67

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

In the meadow we can build a snowman...as the song goes. But with this 1929 Scania Vabis snowplough you won't. To this vehicle all roads and meadows are snow-go areas.

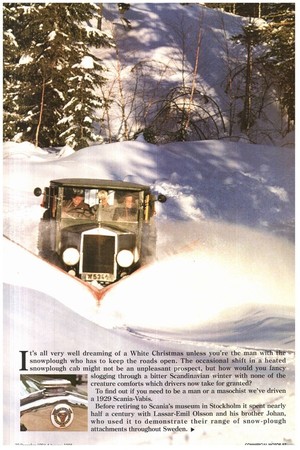

IVs all very well dreaming of a White Christmas unless you're the man with the snowplough who has to keep the roads open. The occasional shift in a heated snowplough cab might not be an unpleasant prospect, but how would you fancy ; slogging through a bitter Scandinavian winter with none of the creature comforts which drivers now take for granted?

To find out if you need to be a man or a masochist we've driven a 1929 Scania-Vabis.

Before retiring to Scania's museum in Stockholm it spent nearly half a century with Lassar-Emil Olsson and his brother Johan, who used it to demonstrate their range of snow-plough attachments throughout Sweden. ■

It was delivered in the October of 1929 (taking Scania-Vabis' annual production to a record 150 trucks) at a list price of SKr1,700 (£147). In 1956 Olsson company records show it was still in good enough condition to justify spending SKr675 on parts from the local dealer. Whether spares for the 26-year-old were available off the shelf is not recorded.

During the winters in between demonstrations the truck was in action clearing roads around the company's base in the district of Lima.

In the summer its three-tonne payload was put to use transporting timber and gravel around the brothers' farm.

As far back as 1961 Lassar-Emil knew that his vehicle was destined for the proposed Scania museum but it was not put out to grass until 1974, with 45 years and 1.5 million kilometers on the clock—still running on its original engine and able to pass its annual test with flying colours. Restoration to museum standard entailed little more than a paint job.

ON THE ROAD

On climbing into an old Swedish vehicle, the first thing you notice is that you got in on the wrong side. The Swedes have only driven on the right since 1967 so vehicles produced before that date have their steering wheels in the proper place—on the right. This is in contrast to the French: while they drive on the right, until the late thirties the steering wheel position was optional Back in 1929 our vehicle had the latest engine; a 6.42-litre straight-six running on petrol and delivering 85hp. In those days such power may have been thought of as extravagant, but pushing a plough through a metre of snow is no easy matter. To ease the pain the four-speed crash box drives through a slow rear axle ratio. While the steering wheel is in a familiar position, other controls take a little getting used to. Cold starting involved testing the cross-cab access as the choke is positioned in front of the passenger. The timing advance/ retard lever in the middle of the steering wheel was standard equipment for the time; the electric starter was a real innovation. There is an ignition key but solenoids were unheard of: to activate the starter a pedal is used to push two heavy-duty contacts together. This starter pedal is positioned above the accelerator, which is also in the "old" place— between the brake and clutch pedals. Once started the engine runs with impressive smoothness given its age, the distance it has covered and the absence of any sound insulation.

Unfortunately, the sewing machine image gets fatally damaged when you select a gear and set off.

The noise from the straight-cut gears in the transmission makes conver sation all but impossible. Clutch and gearshift loads are heavy by today's standards; truck drivers had to be fit in 1929. To compound the problems it's all too easy to jab the brake pedal a few times while getting used to that central accelerator.

Starting off in second the unladen vehicle gets into top gear very quickly. It is attracted to the nearside by the road camber but, noise apart, this is not an uncivilized vehicle until you reach a bend, when turning the steering through all but the smallest angle entails rising off the bench seat to get enough leverage.

Even winding the lock off (self centring was almost nil) takes a fair degree of effort.

These shortcomings would have been major considerations for regular drivers but on a warm summer afternoon, with nowhere to go and lots of time to get there, they weren't too important.

Trundling along through the sunlit Swedish countryside does not really show the vehicle in its natural working environment but does make for an extremely pleasant afternoon. The flexibility of a big petrol engine in an empty truck with a low rear axle ratio all but removed the need for gear changing as we chugged up every hill in top.

With minimal engine braking and no power steering or servo, the gear could be safely disengaged on downhill sections. The great advantage of this was the reduced noise levels while the vehicle gathered what little speed it could from the slope.

This requires confidence in the brakes (controlled by the right-hand pedal) and this confidence was not misplaced, just a little shaken—even as the juddering as the brakes bit rattled our eyeballs.

Like the choke, the handbrake is on the passenger's side of the cab but it also worked well.

In 1929 the acme of electronic wizardry was self-cancelling trafficators. To turn the trafficator on there is a switch, cunningly mounted directly above the steering column and behind the wheel to avoid accidental use. This starts a timer which slowly returns the switch to the off position, thereby cancelling the signal after a preset period.

Unfortunately, getting a vintage truck across some of the busier Swedish roads took longer than the trafficators thought it should. On several occasions this left us making • turns without any indication for other road users.

One thing they didn't have in 1929 was a cab heater. But this might not be a problem in winter as waves of hot air came into the cab from the engine compartment. But you can't turn the heat off in the summer so our trip was definitely a shirt-sleeved affair as the small opening windows don't let in enough fresh air to keep the cab cool. Even the engine was feeling the unusually warm weather and decided to expel a little of its coolant on our run. A short rest in a lay-by cured the problem.

With darkness for weeks on end the Swedes pay a lot of attention to vehicle lights. Our vehicle sported a third headlight in the middle of the windscreen.

This is an amazing gadget—from the inside of the cab, you can rotate the beam through 180° left to right as well as up or down. Very useful for blind bends in snow coveted roads.

Without a load the ride was, not surprisingly, on the hard side. This fact was only relevant on straight stretches of road, those being when you sat on the seat long enough to feel the harshness. The other indication of this was the mirrors. While they were very small, they provide a reasonable view when stationary, but the image breaks up into a blur as soon as you move off.

All in all driving the 1929 Scania was an experience we wouldn't have missed. It also serves as a reminder that, with all the problems of congestion and deadlines, today's drivers still enjoy a level of comfort that would have left the Scania's original crew speechless with envy El by Colin Sowman