WINTER WARMERS

Page 24

Page 25

Page 26

Page 27

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

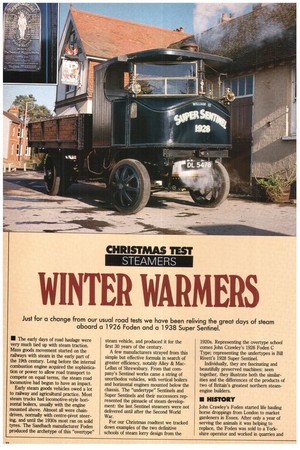

Just for a change from our usual road tests we have been reliving the great days of steam aboard a 1926 Foden and a 1938 Super Sentinel.

II The early days of road haulage were very much tied up with steam traction. Mass goods movement started on the railways with steam in the early part of the 19th century. Long before the internal combustion engine acquired the sophistication or power to allow road transport to compete on equal terms, the steam road locomotive had begun to have an impact.

Early steam goods vehicles owed a lot to railway and agricultural practice. Most steam trucks had locomotive-style horizontal boilers, usually with the engine mounted above. Almost all were chaindriven, normally with centre-pivot steering, and until the 1930s most ran on solid tyres. The Sandbach manufacturer Foden produced the archetype of this "overtype" steam vehicle, and produced it for the first 30 years of the century.

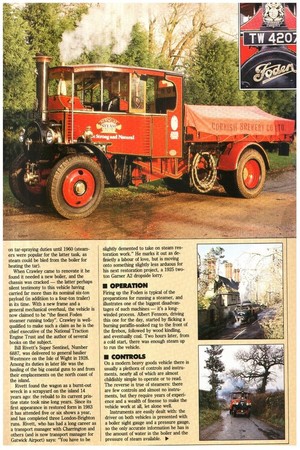

A few manufacturers strayed from this simple but effective formula in search of greater efficiency, notably Alley & MacLellan of Shrewsbury. From that company's Sentinel works came a string of unorthodox vehicles, with vertical boilers and horizontal engines mounted below the chassis. The "undertype" Sentinels and Super Sentinels and their successors represented the pinnacle of steam development: the last Sentinel steamers were not delivered until after the Second World War.

For our Christmas roadtest we tracked down examples of the two definitive schools of steam lorry design from the 1920s. Representing the overtype school comes John Crawley's 1926 Foden C Type; representing the undertypes is Bill Rivett's 1928 Super Sentinel.

Individually, they are fascinating and beautifully preserved machines: seen together, they illustrate both the similarities and the differences of the products of two of Britain's greatest northern steamengine builders.

• HISTORY

John Crawley's Foden started life hauling horse droppings from London to market gardeners in Essex. After only a year of serving the animals it was helping to replace, the Foden was sold to a Yorkshire operator and worked in quarries and on tar-spraying duties until 1960 (steamers were popular for the latter task, as steam could be bled from the boiler for heating the tar).

When Crawley came to renovate it he found it needed a new boiler, and the chassis was cracked — the latter perhaps silent testimony to this vehicle having carried far more than its nominal six-ton payload (in additiion to a four-ton trailer) in its time. With a new frame and a general mechanical overhaul, the vehicle is now claimed to be "the finest Foden steamer running today". Crawley is wellqualified to make such a claim as he is the chief executive of the National Traction Engine Trust and the author of several books on the subject.

Bill Rivett's Super Sentinel, Number 6887, was delivered to general haulier Westmore on the Isle of Wight in 1928. Among its duties in later life was the hauling of the big coastal guns to and from their emplacements on the north coast of the island.

Rivett found the wagon as a burnt-out wreck in a scrapyard on the island 14 years ago: the rebuild to its current pristine state took nine long years. Since its first appearance in restored form in 1983 it has attended five or six shows a year, and has completed three London-Brighton runs. Rivett, who has had a long career as a transport manager with Charrington and others (and is now transport manager for Gatwick Airport) says: "You have to be slightly demented to take on steam restoration work." He marks it out as definietly a labour of love, but is moving onto something slightly less arduous for his next restoration project, a 1925 twoton Garner A2 dropside lorry.

• OPERATION

Firing up the Foden is typical of the preparations for running a steamer, and illustrates one of the biggest disadvantages of such machines — it's a longwinded process. Albert Fensom, driving this one for the day, started by flicking a burning paraffin-soaked rag to the front of the firebox, followed by wood kindling, and eventually coal. Two hours later, from a cold start, there was enough steam up to run the vehicle.

• CONTROLS

On a modern heavy goods vehicle there is usually a plethora of controls and instruments, nearly all of which are almost childishly simple to operate or to read. The reverse is true of steamers: there are few controls and almost no instruments, but they require years of experience and a wealth of finesse to make the vehicle work at all, let alone well.

Instruments are easily dealt with: the driver on both vehicles is presented with a boiler sight gauge and a pressure gauge, so the only accurate information he has is the amount of water in the boiler and the pressure of steam available, • Engine controls are almost as sparse, and in general rather crude. On the Foden three main levers control the engine. The regulator controls the supply of steam to the engine: It lives under the driver's hand all the time, and is both stiff and sensitive, making smooth progress difficult, especially given the whip in the long drive chain. The reversing lever controls the valve timing and hence the direction of rotation of the engine, and there is a three-way valve which allows steam to be fed directly into both the highand lowpressure cylinders for starting from rest or when maximum power is required.

The Sentinel's engine controls are even simpler: the regulator valve is there, as is a camshaft-control lever which acts as the reversing control. There are additional boiler controls: a blower tap for promoting a draught in the firebox, and the injector valve for topping up the boiler water.

The Foden, like the Sentinel, has a boiler feed pump which sees to the topping-up of the boiler while the engine is turning, but needs an injector to do the job while the vehicle — and engine, for these vehicles are direct-coupled — is stationary. The vehicle controls are similarly few in number and simple in function. The Foden's internally-expanding drum brakes (on the rear axle only) are actuated by a conventional foot pedal. There is also an external contracting transmission brake controlled by a horizontal wheel below the steering wheel, and used as a back-up.

The Sentinel's service brakes are similar: foot-operated internally-expanding drum brakes on the rear axle, backed up by a hand brake. In this case, however, the windlass-type handwheel of the early Super Sentinels has been replaced by a much more modern-looking lever with a ratchet. The original screw-down type of parking brake fell victim to construction and use regulations.

In both cases, however, there is a further and most effective retarder built into the driveline. The twenties equivalent of the exhaust brake or Jake brake was the engine reversing lever. Faced with a long downhill run, all the driver had to do was to (carefully!) move the reversing control to a small amount of "reverse" to achieve considerable engine braking.

• TRANSMISSION

Both wagons are chain-driven. The Foden has a single chain driving via a sprocket (which contains a crude differential) to the opposite wheel by way of a shaft. The Sentinel has two chains, each driving its respective rear wheel direct from the end of the crankshaft of the underfloor engine. The other principal difference is that where the Sentinel has only one gear ratio, the Foden has three.

On the Sentinel changing gear means changing one sprocket for another with a different number of teeth: Rivett's vehilce, tailored to the demands of the hilly Isle of Wight, has a 13-tooth drive sprocket and a 33-tooth driven sprocket.

The Foden's three forward (and, of course, reverse) speeds are provided by a set of straight-cut gears on the offside, in front of the driver's mate. Underway they chime in a deafening chorus and are not designed to be changed in the modern way: only when the vehicle is stationary.

At the crest of a rise which the Foden had taken in second, however, driver Fensom demonstrated via some nifty handwork, removing the locking pins from the gear handles and moving them in a swift, clanking motion, that the gears can be shifted on the move, whatever the experts say.

Although the Foden easily loses out in the mechanical noise stakes because of this exposed gearing, it does have the advantage of a quiet(er) ride, as it sits on pneumatic tyres. Originally, like the Sentinel, it sat on steel wheels with solid rubber tyres.

Not only do these tyres make life easier on driver, mate and vehicle (the Sentinel becomes shatteringly noisy and uncomfortable as it nears its design legal speed of 12mph) but they allow much higher road speeds. Flat out on this gearing and with the 51in (1,050nun) diameter solid wheels and tyres, the Sentinel will reach all of 18mph.

Although the Foden's theoretical maximum speed is 16mph, the Crawley machine will, apparently, churn along at a rapid 28mph on these tyres which were fitted, as was common, in the 1930s. Their much greater cross-section adds significantly to the gearing, too.

• UNDER WAY

Both these machines were built before the term "ergonomics" had been applied to the motor vehicleif, in fact, it had even been thought of. The result is that they are heavy and awkward to drive.

A short spell at the wheel of the Foden showed that driving it smoothly is nowhere near as easy as it looks in Frensom's practised hands.

To pull away in the highest gear, the three-way valve is operated to convert the compound engine into a simple twin cylinder unit with both cylinders running on high-pressure steam.

The reversing lever is placed in the fully-forward position (which also increases the supply of steam to the engine) and the regulator is then used to control the motion.

The regulator lever has a lock which has to be released before the lever can be moved, and moving the stiff but sensitive lever to the rear gives instant — and brisk — acceleration. The steering is very heavy and very low-geared. It demands considerable forward thinking by the driver, and requires furious winding when straightening up after a sharp turn. There is also substantial backlash to keep the novice driver on his toes — but even so the Ackerman steering of this late C Type is a considerable improvement over the old-style centre-pivot steering.

The damper on the firebox has been made airtight, so when it is closed the fire will stay in and boiler pressure will be maintained for hours. Open the damper, the fire comes back to life, and off you go.

The Sentinel was famous for its steering gear, which used an Acme-threaded worm-and-nut action. That said, steering a Super Sentinel downhill when fully laden has been described as requiring the biceps and pectorals of a centaur, and the grip of a giant lobster. The observer becomes lost in admiration for the apparent ease with which Bill Rivett manouevres his Sentinel into a small garden and garage.

The most difficult part of driving a Sentinel seems to be keeping its fire in. Even the slightest degree of inattention seems to be rewarded by a buzzing sound as holes burn up through the fire, to be followed by a rapid loss of boiler pressure.