They had ways of making it move

Page 23

Page 24

Page 25

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Graham N/ontgomerie looks at some of e early, and strange, alternatives to petrol power

-HOUGH the heavy lorry and passenger vehicle of today all diesel powered, it was ainly not always like this. diesel engine took over ply because its fuel economy so much better than that of opposition.

it the turn of the century, the rnal-combustion engine was s infancy with horse power four legs) and coal power ig the main aids to load carg. I have been looking at e of the early designs which with the assistance of a nostalgia were not without r problems. .

\t a recent symposium on economy held by Volvo at Gothenburg headquarters, til Haggh — chief engineer gines) — stated quite cateicaliy that "the steam engine once and for all disappeared an alternative [power unit] to its poor efficiency

%Jot so very long ago there ;a revival of interest in steam pulsion prompted by the igent emission regulations by the State of California. ile being all in favour of acing the exhaust emissions :he internal combustion, I e never been able to underid why the rest of the world et along the rest of America should have to adopt such -igent legislation merely bese a freak meteorologicalgraphical combination.

t would probably be cheaper cove California. However, it le season of goodwill, so I'll w it to stay where it is.

3ut although the steamer Dloys external combustion is thus considered a -cleaner" power unit, it has not always enjoyed this reputation.

Emissions of one sort or another have always been a problem in the commercial vehicle industry. It is not just a California-Ralph Nader invention, In the early 1900s, local authorities carried out a running battle against operators (did someone say things haven't changed?) of steam wagons on the grounds that their boilers did not consume their own smoke.

Many summonses were taken out under the "1878 Locomotives and Highways (Amendment) Act because the police argued that a steam wagon could not be considered as a light locomotive if it emitted smoke or exhaust steam from the funnel. Thus the battle between road and rail continueth unto the third and fourth generation.

The problem was that the emancipatory Act of 1896 had defined a light locomotive in .a curiously defensive manner as one which did not exceed three tons (not tonnes — this is long before "'harmonisation") unladen and which did not emit smoke or visible vapour "except from any temporary or accidental cause".

The constabulary of the period had taken it upon themselves to decree that any continuous emission of smoke or steam meant that the vehicle in question was thus considered as a traction engine and not a light locomotive. Thus the spectre of the GV9 was first seen upon the land.

It might interest operators who feel that legislation is not their friend to recall a case in 1905 which proves that the battle between the paperwork and the system is not a symptom peculiar to the 1970s.

In that year there was a case concerning Messrs VV. J. Lobjoit and Sons, a firm of market gardeners in Hounslow. The alleged emission of smoke was due to a hold up in Piccadilly because of roadworks with the resultant stoppage causing loss of draught in the furnace and a consequent deadening of the fire.

The magistrate decided that a traffic jam in Piccadilly was a more or less permanent occurrence and so did not qualify under the let-out clause of "temporary or accidental". But the main outcome of the case was that it caused even further confusion over the definition of a steam-powered wagon.

Because of the risk of prosecution, the manufacturers went to great lengths to prevent the emission of smoke or visible vapour — or rather they showed that the vehicle was so constructed that it should consume its own smoke. A case of -justice

With a steam-powered ehicle, a bright red fire would ot cause any smoke because all le volatile parts of the coal sould have been driven off )aving nothing but solid arbon.

As the air passed through the ire bars, the oxygen combined vith the amount of carbon lecessary to produce carbon nonoxide or carbon dioxide oath of which are colourless).

However, when a fresh load 4 coal was dumped on the top, II the hydrocarbons were !riven off as gases because the lew coal was "baked' before it lethally began to burn. If a tream of air was brought into ontact with the gases while hey were still hot enough to 'urn, they were consumed very 'ffectively.

On the other hand, if only a. mall amount of air was avail-. ble, the gases decomposed: vith hydrogen combining with ixygen to form water, and ninute particles of solid carbon: vere freed in the form of smoke., -hus a good supply of air wasi tecessary as soon as there was! iny sign of smoke from the funel,

The usual practice of the time vas to open the fire door and to egulate the amount of extra air ry how far the door was opened.

This was fine as long as the thicle was moving, but when it topped the induced draught eased, so it was then necessary o provide some form of assistInce.

This usually took the form of a upplementary steam jet in the unnel which could be turned on

o induce a draught when the: :ngine was not running. Steam ,ngines do not "tick over', loot forget.

The question of exhaust team, as opposed to exhaust moke, was a thorn in the side of. nany steamer operators who ound themselves being fined or smoke where 'whitevisible 'apour" had been the sole.

• ause of offence. Thus some nethod of disposing of the team was necessary after it had lone its work in the cylinders.

The exhaust steam from an !ngine on a hot day usually disersed invisibly, but on a cold lamp day much of it was conlensed directly it left the funnel, )roducing dense clouds of very ,isible vapour.

As the manufacturers and rperators were less than con,inced that the law•would take iny notice of the vagaries of the veather, the steamer builders vent to great lengths to dry the ixhaust steam to render the

emissions invisible at all times.

The diagram shows the method used in 1905 by Fodens. On the Foden steamed of the time, a locomotive type of boiler was employed with the cylinders mounted on the top of the boiler as in traction-engine practice. The exhaust was led from the cylinders to a circular casteron: box secured across the upper part of the smoke box. The: further end of the exhaust box' was flanged and a plate extended at the lower end and bent to act as a fixing bracket, effectively sealing it.

In the upper part of this box was a small hole through which the steam ultimately found its way up to the funnel. The effect of turning the exhaust into such a box was to destroy any noise it might cause because each puff was directed towards the end of the box and not towards the escape hole. The steam thus left the box silently while any water it contained fell to the bottom of the box and was gradually evaporated.

As the outside of the box was in direct contact with the pro ducts of combustion, it got fairly hot and thus superheated the exhaust stream.

Thus it can be seen that the steam engine was not without its problems when it came to emissions — be they visible or otherwise.

Because of the present energy Crisis and the possibility of running out of oil, many research organisations have been showing renewed interest in alternative forms of propulsion to the familiar diesel or petrol engine coupled to some form of mechanical transmission.

In many cases, this has merely been to resurrect some theories which had been deve loped earlier, before the petrol and diesel engines had gained such a firm hold over electric vehicles, friction drive, steamers and so on.

One such system was the petrol-electric combination in which an engine was direct coupled to a generator which supplied electrical energy to

motors connected to the road wheels which meant that the clutch, gearbox and conventional final drive could be dis-. pensed with.

Even for the early transport pioneers it was necessary to de fine their aims. For example, the bus company had two main considerations — what system would provide the passengers with the cheapest means of reaching their destination, and

what system would do this while being the most profitable to the company?

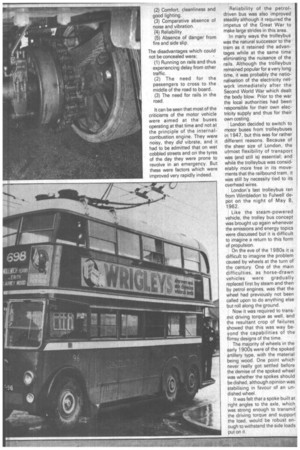

In the early years of this century there began the war, ferocious at times, between the supporters of electric traction and the new-fangled motorbus. In 1906 the relative advantages and disadvantages were summed up thus: Petrol driven bus — advantages (1) Greater speed from point to point due to the comparative freedom of movement about the roads.

(2) Ability to vary the service from one road to another thus enabling the most profitable routes to be developed without loss of capital.

(3) Ability to draw up by the pavement. (4) Absence of rails in t roadway.

Petrol driven bus -disa vantages (1) High cost of operation (2) Noise (3) Smell — mainly frc burnt lubricating oil.

(4) The danger of side-slip skid to you and me!] (5) Fire (6) Vibration (7) Danger to other veho users (8) Unreliability, need hardly add that i above comments were made an advocate of the electr powered tram who could tr not be described as being wi out bias. His comments in f. our of the tram were as follou\ (1) Lowest known costs operation. (2) Comfort, cleanliness and good lighting.

(3) Comparative absence of noise and vibration.

(4) Reliability (5) Absence of danger from fire and side slip.

The disadvantages which could not be concealed were: (1) Running on rails and thus experiencing delay from other traffic.

(2) The need for the passengers to cross to the middle of the road to board.

(3) The need for rails in the road.

It can be seen that most of the criticisms of the motor vehicle were aimed at the buses operating at that time and not at the principle of the internalcombustion engine. They were noisy, they did vibrate, and it had to be admitted that on wet cobbled streets and on the tyres of the day they were prone to revolve in an emergency. But these were factors which were improved very rapidly indeed.

Reliability of the petroldriven bus was also improved steadily although it required the impetus of the Great War to make large strides in this area.

In many ways the trolleybus was the natural successor to the tram as it retained the advantages while at the same time eliminating the nuisance of the rails. Although the trolleybus remained popular for a very long time, it was probably the nationalisation of the electricity network immediately after the Second World War which dealt the body blow. Prior to the war the local authorities had been responsible for their own electricity supply and thus for their own costing.

London decided to switch to motor buses from trolleybuses in 1947, but this was for rather different reasons. Because of the sheer size of London, the utmost flexibility of transport was (and still is) essential; and while the trolleybus was considerably more free in its movements that the railbound tram, it was still by necessity tied to its overhead wires.

London's last trolleybus ran from Wimbledon to Fulwell depot on the night of May 8, 1962.

Like the steam-powered vehicle, the trolley bus concept was brought up again whenever the emissions and energy topics were discussed but it is difficult to imagine a return to this form of propulsion.

On the eve of the 1980s it is difficult to imagine the problem caused by wheels at the turn of the century. One of the main difficulties, as horse-drawn vehicles were gradually replaced first by steam and then by petrol engines, was that the wheel had previously not been called upon to do anything else but roll along the ground.

Now it was required to transmit driving torque as well, and the resultant crop of failures showed that this was way beyond the capabilities of the flimsy designs of the time.

The majority of wheels in the early 1900s were of the spoked artillery type, with the material being wood. One point which never really got settled before the demise of the spoked wheel was whether the spokes should be dished, although opinion was stabilising in favour of an undished wheel.

It was felt that a spoke built at right angles to the axle, which, was strong enough to transmit the driving torque and support .the load, would be robust enough to withstand the side loads put on it.