SteyrPuch Haflinger4x4

Page 32

Page 33

Page 34

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

E MARK II HAFLINGER, like the earlier version roadtested in 1961, produced some quite startling results. In negotiating rough country it can have few equals short of tracked vehicles. But the latest model could not live up to the original as regards fuel consumption: although performance has remained almost identical despite a heavier payload, its bigger engine and higher gearing have taken their toll.

The Haflinger has unusual constructional details. It employs a central tube as the backbone of the chassis, to which at the rear end is attached the engine/gearbox unit. The transmission is taken forward through the rear drive unit—via a shaft running within the tube to the front differential. Four swinging arms carry the wheel assemblies, suspension being by coil springs. The driving shafts pass through the swinging members terminating at the outer ends in spurgear hub reduction units.

The engine is an air-cooled flat twin-cylinder petrol unit of 643c.c. which with a modified camshaft, carburetter and induction manifold now develops 30 bhp gross at 4,800 rpm. The original four-speed gearbox has been replaced by a five-speed unit with synchromesh on all gears and whereas the overall final drive ratio was 8.0 to 1 it is now 6.61 to 1.

I believe the high gearing is to blame for the poor fuel consump,m,,t,T.,..v..%.A0,..9amve

lion for throughout the test the machine was extremely unhappy in top. It needed only the slightest adverse conditions to bring the road speed down to a point where I had to change to a lower ratio. And in most cases when this was attempted the extremely effective governor gear prevented sufficient engine speed being obtained to take advantage of the new ratio until road speed had dropped even further.

A differential lock is incorporated in both transmission units and these can be engaged and disengaged while the vehicle is in motion, as can the four-wheel-drive.

The diff-locks are, I believe, the secret of the remarkable crosscountry performance of this vehicle because, when these are engaged together with the four-wheel-drive, the transmission presents a locked-together entity. Slipping of any one wheel causes no loss of drive on those retaining adhesion.

This completely positive connection with the ground, coupled with a low gross weight, allows the vehicle to traverse all but the softest mud. Hardly a tyre mark is left when crossing a wet and freshly ploughed field!

The Haflinger will cross ditches as deep as itself and little more than twice its 60in. wheelbase in width, climb 45deg banks surfaced with mud and leaves with never so much as a trace of wheelspin. It descends slopes so steep that the front-mounted winch digs into the ground before levelling off, still landing on its wheels.

Travelling at fairly high speeds across country it is easy to hit an unseen hump in long grass—usually a disaster which leaves the vehicle upturned. During the test we ran into a hidden hump and although the machine landed at an angle of about 40deg on its nearside front wheel, it came down again right side up, fit to carry on. So light is the Haflinger, however, that the easiest way to work on its underside is simply to tip it up on its side, so even had it turned completely over, two of us on the test could have righted it between us.

For a gross load of 19.75cwt the figure of 30 bhp is liable to convey an impression of sprightly performance. However, one is inclined to expect a lot more performance than I found from a vehicle of this size and my one complaint about the Haflinger is that it is short of power for road-going.

I mentioned earlier the extremely effective governor fitted to the vehicle and the part it played in the characteristics of the machine. It is possible to cut this out, by removing the vee-belt by which it is driven, allowing engine speed to be controlled purely by the throttle pedal. During part of the test I did just this so that I could evaluate the performance of the engine in its ungoverned state. Although with the governor in action the road speeds proved to be 4, 9, 17, 28 and 47 mph in the respective gears, when it was removed the only advantage felt was that the road speeds in 2nd, 3rd and 4th went up to 12, 22 and 30 mph respectively. Top gear speed did not change and this confirmed my suspicions about the overgearing. Under ideal conditions this would read 50 mph with the governor on. Ungoverned it still reached 50 on the same section of road.

Fuel consumption Other than for the unladen test, fuel-consumption results did not differ greatly from those achieved in 1961. But as the gross load was 7.5 cwt greater and the average speeds higher on each occasion, the time-load-mileage factors are significantly better.

Two fully laden runs were done over the same route, a stretch of A6 between Barton-in-the-Clay and Clophill, one aimed at producing an average of as near to 30 mph as possible and the other at maximum speed. The 30 mph run produced and average speed of 31.6 mph and 26.7 mpg fuel consumption and the fullspeed run, 34.6 mph and 24.0 mpg consumption. The full-speed run would normally be done on M1 but on this occasion there was little point owing to the low top speed.

The unladen consumption test saw the vehicle pushed fairly hard to make the recorded average of 30.8 mph owing to baulking by heavy traffic and the consumption was consequently fairly low at 27.4 mpg.

Apart from some oversteer which proved to be a case of not being used to the machine, the Haflinger handled perfectly. It took no more than four of five miles to overcome the steering problem and from that time on I found its high speed accuracy quite fas cinating. All the controls are light to use, my only complaint being that the spring loading on the gearlever is too light, and on several

occasions during the test I found that I had engaged 1st gear instead of my intention which was 3rd. I feel that this could with advantage be made heavier.

Cab heating on the Haflinger is surprisingly efficient, giving out a considerable amount of heat. Alas it is not perfect, for it picked up exhaust fumes as well when running in a following wind.

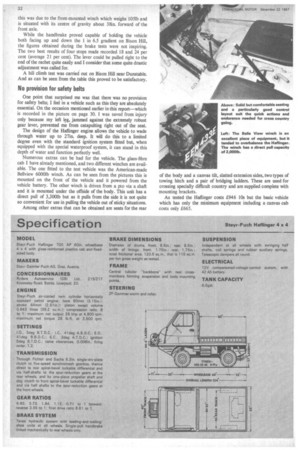

One of the most noticeable improvements in the vehicle since the original test is the glass-reinforced plastics cab. I know it is not meant to be luxurious but I did not like the draught whistling around the back of the driving seat.

Vision is very good but I found it impossible to get my arm out of the sliding portion of the door-glass to make hand signals —a small and niggling complaint, perhaps. Nevertheless a vehicle of this sort will quite often be turning off highways at the most unlikely places, and I feel that under these conditions hand signals are an absolute necessity.

Soft, springy seats are the last thing one wants for comfort when travelling across country. The makers of this machine have

'found what I consider to be one of the most comfortable arrangements I have experienced for this job. And I have no complaints from the road-going point of view either.

Brake performance of this vehicle is something to be experienced. The actual stopping distances recorded were not good, but the manner in which the vehicle stopped was fascinating to say the least. At 30 mph I applied full pressure to the footbrake. What happened then was not clear until I saw the pictures taken by CM photographer Harry Roberts, for although the Tapley meter jumped right off the end of the scale, the measured distance proved to be 50ft. Two or three more tries, but still no satisfactory figures although marking on the road showed only a short skid close to the gun mark. More head-scratching and I tried less pedal pressure; better results but not what I would have liked.

When the pictures arrived on my desk the reason was clear— as soon as full pressure was applied the machine hopped up on to its front wheels and stayed in that attitude for quite a distance, so eliminating the effect of the rear-wheel brakes. In all probability this was due to the front-mounted winch which weighs 105Ib and is situated with its centre of gravity about 38in. forward of the front axle.

While the handbrake proved capable of holding the vehicle both facing up and down the 1 in 6.5 gradient on Bison Hill, the figures obtained during the brake tests were not inspiring. The two best results of four stops made recorded 18 and 24 per cent (average 21 per cent). The lever could be pulled right to the end of the rachet quite easily and I consider that some quite drastic adjustment was called for.

A hill climb test was carried out on Bison Hill near Dunstable. And as can be seen from the table this proved to be satisfactory.

No provision for safety belts

One point that surprised me was that there was no provision for safety belts; I feel in a vehicle such as this they are absolutely essential. On the occasion mentioned earlier in this report—which is recorded in the picture on page 30. I was saved from injury only because my left leg, jammed against the extremely robust gear lever, prevented me from catapulting right out of the seat.

The design of the Haflinger engine allows the vehicle to wade through water up to 27in. deep. It will do this to a limited degree even with the standard ignition system fitted but, when equipped with the special waterproof system, it can stand in this depth of water and function perfectly well.

Numerous extras can be had for the vehicle. The glass-fibre cab I have already mentioned, and two different winches are available. The one fitted to the test vehicle was the American-made Bellview 60001b winch. As can be seen from the pictures this is mounted on the front of the vehicle and it powered from the vehicle battery. The other winch is driven from a pto via a shaft and it is mounted under the offside of the body. This unit has a direct pull of 3,3001b but as it pulls from the side it is not quite so convenient for use in pulling the vehicle out of sticky situations.

Among other extras that can be obtained are seats for the rear of the body and a canvas tilt, slatted extension sides, two types of towing hitch and a pair of bridging ladders. These are used for crossing specially difficult country and are supplied complete with mounting brackets.

As tested the Haflinger costs £946 lOs but the basic vehicle which has only the minimum equipment including a canvas cab costs only £665.