Vanguard

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Rustproofing can virtually eliminate corrosion on vans

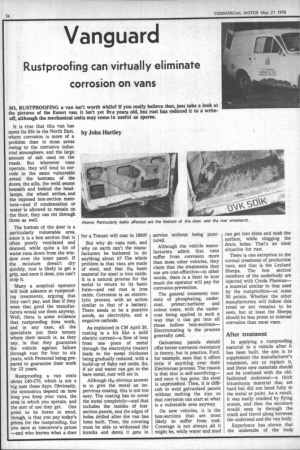

SO, RUSTPROOFING a van isn't worth while? If you really believe that, just take a look at the pictures of the Escort van; it isn't yet five years old, but rust has reduced it to a writeoff, although the mechanical units may come in useful as spares.

by John Hartley

It is true that this van has spent its life in the North East, where corrosion is more of a problem than in most areas owing to the corrosive industrial atmosphere, and the large amount of salt used on the roads. But wherever vans operate, they will tend to corrode in the same vulnerable areas: the bottoms of the doors, the sills, the weld seams beneath and behind the headlamps, the wheel arches, and the exposed box-section members—and if condensation or water is allowed to remain on the floor, they can rot through there as well.

The bottom of the door is a particularly vulnerable area, since it is a box section that is often poorly ventilated and drained, while quite a lot of water runs down from the window over the inner panel. If the moisture doesn't dry quickly, rust is likely to get a grip, and once it does, you can't stop it.

Many a sceptical operator will look askance at rustproofing treatments, arguing that they can't pay, and that if they were •that good the manufacturers would use them anyway. Well, there is some evidence that rustproofing does work, and in any case, all the specialists put their money where their mouth is, as they say, in that they guarantee the vehicle against failure through rust for four to six years, with Protectol being prepared to guarantee their work for 12 years.

Rustproofing a van costs about £40-£70, which is not a big sum these days. Obviously, the economics depend on how long you keep your vans, the area in which you operate, and the sort of use they get. One point to be borne in mind, though, is that you pay today's prices for the mistproofing, but you save at tomorrow's prices —and who knows what a door for a Transit will cost in 1980?

But why do vans rust, and why on earth can't the manufacturers be bothered to do anything about it? The whole problem is that vans are made of steel, and that the basic material for steel is iron oxide. It is a natural process for the metal to return to its basic form—and red rust is iron oxide. Corrosion is an electrolytic process, with an action similar to that of a battery. There needs to be a positive anode, an electrolyte, and a negative cathode.

As explained in CM April 30, rusting is a bit like a mild electric current—a flow of ions from one piece of metal through the electrolyte (water) leads to the metal thickness being gradually reduced, with a build-up of flaky red oxide. So, if air and water can get to the bare metal, rust will set in.

Although the obvious answer is to give the metal an impervious coating, this is not too easy. The coating has to cover the metal completely—and that includes the insides of box section panels, and the edges of holes drilled after the van has been built. Then, the covering must be able to withstand the knocks and dents it gets in service without being punctured.

Although the vehicle manufacturers admit that vans suffer from corrosion more than most other vehicles, they claim that the treatments they use are cost-effective—in other words, there is a limit to how much the operator will pay for corrosion-prevention.

The general treatment consists of phosphating, undercoat, primer/surfacer and colour coats, with the undercoat being applied in such a way that it can get into all those hollow box-sectionsElectrocoating is the process generally used.

Galvanised panels should offer better corrosion resistance in theory, but in practice, Ford, for example, says that it offers little if anything over their Electrocoat process. The reason is that zinc is self-sacrificing— and once it has gone, the steel is unprotecited. Then, it is difficult to weld galvanised panels without melting the zinc so that corrosion can start at what is a vulnerable area anyway.

On new vehicles, it is the box-sections that are most likely to suffer from rust. Coverage is not always all it might be, while water and mud can get into them and soak the surface, while clogging the drain holes. That's an ideal situation for rust.

There is one exception to the normal treatment of production vans, and that is the Leyland Sherpa. The box section members of the underbody are injected with Croda Plaswaxa material similar to that used by the rustproofers—at some 30 points. Whether the other manufacturers will follow this trend or not remains to be seen, but at least the Sherpa should be less prone to internal corrosion than most vans.

After treatment

In applying a rustproofing material to a vehicle after it has been built, the aim is to supplement the manufacturer's treatment, not to replace it, and these new materials should not be confused with the oldfashioned underseal—a thick bituminous material that set hard but did not bond fully to the metal or paint. As a result, it was easily cracked by flying stones, and then the moisture would seep in through the crack and travel along between the underseal and the van body.

Experience has shown that the underside of the body should be covered including the wheel arches, and, of course, to inject into all the box sections, including the doors. Obviously, the material sprayed on to the body needs to be different from that injected into the box-section members. In both cases, the material must insulate the metal from air, water and salt, while it must remain stable, so that its chemical characteristics do not change.

But the material injected into the box section members must be thin, with a low viscosity, and must have some capillary action so that it can find its way into the seam and joints. Then, it should not harden too quickly, or it will be unable to penetrate into the seams before hardening.

Both materials must bond chemically to the body, and they must have self-sealing properties, and be fairly flexible. The external material must be able to withstand the attack of flying stones as well.

To meet these requirements, a petroleum-based metalloorganic material was developed in the USA some 20 years ago. There are generally two varieties, a thin one for the box sections, and a thicker material for the external surfaces. Incidentally, as with paint so with rustproofing materials; a great thick layer is not necessarily better than a thin layer—the important point is complete coverage.

There are six main rustproofing specialists in the UK and they use similar materials and methods of application. As a rule, the van should be treated as soon as it is purchased, and for the guarantee to operate, most of the companies insist on rustproofing before the van is three months old. Most of them are proofed against rust, with a guarantee if an inspection proves that the body is in good condition, and without a guarantee if not; but this depends on the individual company and the vehicle. It is probably expecting a bit much to gain anything from rustproofing a van of more than 12-18 months old, though.

Overnighter

Before the van can be rustproofed, it must be clean, so a power wash and dry may be needed. There are, of course, two sides to the application of the materials. Material is sprayed all over the underside of the van, up into the wheelarches, behind the headlamps, and into any other areas that are a bit critical. Then, the material has to be injected into the box sections, and this involves the drilling of a number of holes, usually lin diameter.

The specialists analyse the designs of the vans when they are introduced, and prepare data sheets showing their operators where to drill the holes, and how to apply the material. The general principle is that the spray nozzle is on the end of a long probe, which is flexible enough to bend around the corners so that complete coverage can be obtained, in theory. Endrust claims that its nozzles atomise the material, and so blow a fine fog into the box section, which should give a more uniform covering.

When the spraying is finished, it is important that the vehicle should be left so that the surplus sealant can drain away, while that bonding to the panels can cure properly—if the van is driven off too early, the skin could be punctured by flying stones. This means that the van is normally off the road for about one and a half days, with the bulk of this time being needed to effect a sound cure.

There are about 1,000 rustproofing stations in the UK, mostly franchise operations, although a few are owned by the specialist suppliers of the materials. And how much do they charge? For a Transit van, Cadulac quotes a price of £50, Endrust £45, Dinitrol £82, Protectol £70, and Ziebart £68, all these figures being subject to discount for fleets. Total protection quotes £21-£.25 "for fleet operators."

Free inspection

Guarantees vary widely, though. ProtectoI offers a 12year guarantee, so long as the vehicle is presented for an annual inspection, for which a charge is made. Generally, the guarantees are from four to six years, with a free inspection after two years—Endrust four or six years, depending on agreement, Ziebart five years, Totalprotection five years, and Dinitrol six years.

However, Totalprotection also offers a non-transferable 10-year guarantee subject to annual inspection and retreatrnent if necessary, paid for by the client. The fact that this is non-transferable tends to defeat the object of the exercise as far as the owner is concerned, and the principle of non-transferable warranties is not really acceptable these days anyway.

Although the guarantee may look very nice, and the company may honour it to the letter, any subsequent retreatment means time off the road, which is expensive. So it is important to use a good system, especially since many of the operators are franchises, and we all know that although the ingredients of a Wimpy may be the same everywhere, the state of the places where they are served can vary enormously.

So does this apply with rustproofing as well? There is no doubt that it is the application of the materials that is crucial, especially that used in the box section members—where you can't be sure whether they have done the job properly or not. Equally, there is no doubt that some operators have been somewhat careless in the way in which they injected the material but now that they can use fibre optic lamps to inspect the hollow members, there is really no excuse for not doing the job properly.

One way of checking the job is to remove the door trim panels when the van comes back, and you will soon see how well that part of the job has been done.

Recently, the Ziebart system gained the AA Seal of Approval, which was given only after a thorough investigation of the process and its application. In fact, this was done on a station-to-station basis, and not all of them have won it, so if you choose Ziebart, make sure that you find a station with the Seal of Approval.

In theory, the Endrust system should be good, and it needs to be an improvement on the early treatment, if the experience of Mr Charles Stanley, transport manager, mechanical of Birmingham Post and Mail is anything to go on. He started applying lanolin to the box-section members of vans after the war, and then tried Shell Ensis before going over to Endrust about five years ago. "If they get it there, it's good," he says, but found that in the early days, the operators seemed to miss some areas. Mostly, the vans that have been treated are J4s, Transits and Commer 2500s.

Mr Stanley says that the process does seem to give a slightly longer life, but is sceptical about claims for higher resale value. He is just selling the 1971 models and says: "You don't get anything extra for it; you only get £100£200 for a van like these, unless it is rotted right through, of course, and then you get hardly anything."

Bad corrosion

Mr Jim Brown, head of the motor transport group for the North Eastern region of the Post Office, has had some 180 vans treated by Protectol since the autumn of 1974, and before that has some experience with Tectyl treatment. The vehicles involved have been Minivans, Marinas, Sherpas and Commer vans. He says that Cleveland is the worst area in his region for corrosion, and that it is so bad there that most of the vans are treated with a specially dense paint, Williamson's Ripo thin.

Generally, the Post Office keeps its Minivans for five to six years, and the others for a little longer, and Mr Brown is hoping to extend the life by a year or two. He reckons that nowadays, the mechanical units are no problem really, but that the conditions in which some of the vans operate are so bad for corrosion that his men are often called on to do some very tricky body repairs. So far, it is too early to say that the Protectol treatment is a success, but the evidence suggests that it will pay off.

The East Sussex County Council started to rustproof its vans three years ago, and although the material "seems to be effective," it considers it too early to say whether the life of the van is increased. In fact, the number of local authorities now using rustproofing treatments is high—Ziebart claims to have over 60 local authorities and over 100 companies among its customers!

So are these people right, or are the sceptics, who say that it isn't worth it, right? There is little doubt that if a rustproofing material is applied correctly, it will extend the life of the vehicle, probably by two or three years at least.

Equally, there is no doubt that the vehicle manufacturers have improved the treatments they apply over the past five years. For example, the Sherpa van now sets a high standard, and if you bought one with the aim of keeping it for two or three years, then rustproofing would seem to be a luxury. But if you keep your vans for five or six years, and you have rust problems, then you should consider rustproofing.

But will you gain anything on resale value? Well, if you are currently disposing of rotten vans like the Escort shown in our pictures, then rustproofing must be worthwhile; it can't really fail to pay for itself, can it?

Cadulac Chemicals, Old Boston Trading Estate, Penny Lane, Haydock, St Helens, Merseyside.

Endrust Auto-Truck Rustproofing Co, Tyburn Road, Birmingham B24 9PD.

HUCO-GML Ltd (Dinitrol treatment), 39 Market Place, Chippenham, Wilts.

Protectol (Rustproofing) Ltd, Commercial Yard, Galgate, Barnard Castle, Co Durham DL12 8BG.

Totalprotection Ltd, Abbeydale Road, Alperton, Wembley, Middx HAO 1QA.

Ziebart, Great Britain Ltd, Ziebart House, Dominion Way, Worthing, Sussex 13N14 8LU.