By A. J. P. WILDING, AM I Mech E, IVIIRTE

Page 61

Page 60

Page 62

Page 63

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

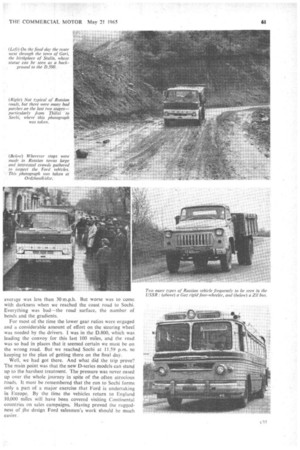

TO cover 1,500 miles in five days in trucks through a strange country is no sinecure. It is even worse when the roads are not of a very good standard and where mountain ranges have to be crossed. Such was the case with the proving run made by Ford from Kiev to Sochi on the Black Sea accompanied by journalists from the UK and the Continent. I have reported briefly on it in the past two issues of The Commercial Motor. By the time we had picked up the vehicles at Kiev •the Ford drivers had already clocked more than 1,500 miles through Belgium, Germany and Czechoslovakia and in the last country the suspensions and chassis had been given ;a real hammering on what we were told were really atrocious road surfaces.

The fuel-consumption figures obtained for the aecom.panied part of the run (as quoted in last Week's issue) can be only of academic interest as it is unlikely that road

and traffic conditions in Russia will be comparable with any met by a British operator. It would have been possible to get some idea of normal fuel consumption if figures for the separate sections of the run had been obtainable, but this was impossible. Also the three I3-series lorries were not carrying full loads.

The journey was completed in five stages—Kiev to Kharkov, Kharkov to Rostov-on-Don, Rostov to Pyatigorsk, Pyatigorsk to Tbilisi and Tbilisi to Sochi.

Dealing with each day's run in turn, from Kiev to Kharkov was 296 miles and at first—for some 15 Miles— the road surface was fairly good and the road was wide. But from this point, and in fact for the whole journey to Sochi afterwards, the roads were only 20 ft. or so widewith earth shoulders ort.both sides. The surface was not very smooth, which caused a .fair amount of continued on page 60

pitching on the coach, but the lorries handled well and their suspensions were well up to the job.

For the whole way on the first day the road was very flat with no appreciable gradients and was straight for mile after mile. We passed through few towns and with light traffic all the time it was possible to keep a steady speed of between 55 and 60 m.p.h. to average 50 m.p.h. • whilst on the run.

The second day from Kharkov to Rostov saw similar roads and traffic conditions for about 200 of the 289mile leg. After this point had been reached the country was more hilly and the road surface deteriorated, being badly broken up in places. was driving the D.500 when we reached the more difficult section and here it started raining very heavily, causing the surface to become treacherous—the road surfaces were generally well polished. At times there was a tendency for the vehicle to slip towards the hard shoulder even when on the straight: this made it necessary to reduce the speed, but even so an average of about 45 m.p.h. was recorded for the day.

From Rostov to Pyatigorsk (310 miles) on the third day there was much more traffic, but it was still possible to run at up to 60 m.p.h. because the roads were much improved and flatter. But later. in the day rain came down again, making the road surface dangerous. The need for caution when going on to the hard shoulder was shown on one of the short stops made. The shoulder was obviously slippery and all except one of the vehicles kept to the tarmac. The one that did not was the D.800, which was being driven by a journalist, and he got both his nearside wheels on to the earth and then braked. Immediately, all wheels locked. The vehicle slid to the edge of the shoulder and was only prevented from going over the edge --a 4 ft. drop into a field—by the right-hand front wheel sinking into soft earth. This could have been a serious situation, but fortunately towing equipment was carried and the D.500 pulled its brother out without much difficulty. The roads dried out very quickly when the sun made an appearance about mid-day and allowed a fast run in the afternoon to arrive at Pyatigorsk 45 minutes ahead of schedule.

Few of us were looking forward to the run from Pyatigorsk to Tbilisi on the fourth day as there was a report that snow was falling on the pass we were to take over the Caucasians. Ten shovels were purchased as a precaution, but as it happened these were not required! Even though we. did not have to shovel the vehicles out of drifts, however. the run was pretty hard on the lorries. At first is was reasonably flat. but after a stop for lunch at Ordzhonikidze we started climbing endless gradients with many hairpin bends, reaching 8,000 ft. or so before starting to descend on similar roads. We passed above the snow line and snow was banked 12 ft. highin places at each side of the vehicle. We thought we had done very well to get over the range until we found a bus on its normal route stationary waiting for us to get through.

The road into Tbilisi was fairly level after the mountains, as it was at the start of the final day which involved the 406-mile section to Sochi. This part of Russia appeared much more prosperous than the earlier part we passed through, with many more cars and commercial vehicles about. This did not help in obtaining high average speeds, but having more effect on speed was another range of the Caucasians we had to pass over. This was lower than the first one, the maximum height being around 3,000 ft., but again there were many long gradients and hairpin bends.

The journey was made more difficult by the fact that when the road was not going up or down it passed through endless inhabited areas and people and farm anihials wandered aimlessly about the road. On these sort of roads speed was of much less importance than safety and the

average was less than 30 m.p.h. But worse was to come with darkness when we reached the coast road to Sochi. Everything was bad—the road surface, the number of bends and the gradients.

For most of the time the lower gear ratios were engaged and a considerable amount of effort on the steering wheel was needed by the drivers. I was in the D.800, which was leading the convoy for this last 100 miles, and the road was so bad in places that it seemed certain we must be on the wrong road. But we reached Sochi at 11.59 p.m. so keeping to the plan of getting there on the final day.

Well, we had got there. And what did the trip prove? The main point was that the new D-series models can stand up to the harshest treatment. The pressure was never eased up over the whole journey in spite of the often atrocious roads. It must be remembered that the run to Sochi forms only a part of a major exercise that Ford is undertaking in Europe. By the time the vehicles return to England 10,000 miles will have been covered visiting Continental countries on sales campaigns. Having proved the raggedness of the design Ford salesmen's work should he much easier.