MISSION IMPOSSIBLE?

Page 52

Page 53

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

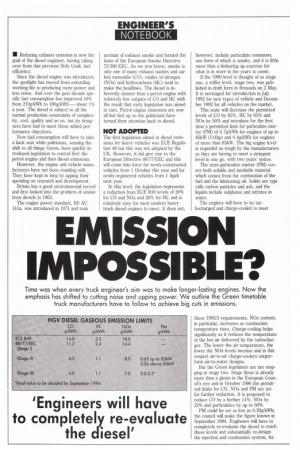

Time was when every truck engineer's aim was to make longer-lasting engines. Now the emphasis has shifted to cutting noise and upping power. We outline the Green timetable truck manufacturers have to follow to achieve big cuts in emissions.

• Reducing exhaust emission is now the goal of the diesel engineer, having taking over from that previous Holy Grail, fuel efficiency.

Since the diesel engine was introduced, the spotlight has moved from extending working life to producing more power and less noise. And over the past decade specific fuel consumption has improved 10% from 210g/kWh to 190g/1Wh — about 1% a year. The diesel is subject to all the normal production constraints of complexity, cost, quality and so on, but its designers have had to meet these added performance objectives.

Now fuel consumption will have to take a back seat while politicians, sensing the shift to all things Green, have quickly introduced legislation to control first the petrol engine and then diesel emissions.

However, the engine and vehicle manufacturers have not been standing still. They have kept in step by upping their spending on research and development.

Britain has a good environmental record and first looked into the problem of smoke from diesels in 1963.

The engine power standard, BS AU 141a, was introduced in 1971 and took account of exhaust smoke and formed the basis of the European Smoke Directive 72/306 EEC. As we now know, smoke is only one of many exhaust nasties and carbon monoxide (CO), oxides of nitrogen (NOx) and hydrocarbons (HC) tend to make the headlines. The diesel is inherently cleaner than a petrol engine with relatively low outputs of CO and HC with the result that early legislation was aimed at cars. Petrol engine emissions are now all but tied up so the politicians have turned their attention back to diesel.

NOT ADOPTED

The first legislation aimed at diesel emissions for heavy vehicles was ECE Regulation 49 but this was not adopted by the UK. However, it did give rise to the European Directive 88/77/EEC and this will come into force for newly-constructed vehicles from 1 October this year and for newly-registered vehicles from 1 April next year.

At this level, the legislation represents a reduction from ECE R49 levels of 20% for CO and NOx and 30% for HC and is relatively easy for most modern heavy truck diesel engines to meet. It does not, however, include particulate emissions, one form of which is smoke, and it is little more than a limbering up exercise for what is in store in the years to come.

If the 1990 level is thought of as stage one, a stiffer level, stage two, was published in draft form in Brussels on 2 May. It is envisaged for introduction in July 1992 for new types of vehicle and December 1992 for all vehicles on the market.

This state will decrease the permitted levels of CO by 65%, HC by 65% and NOx by 50% and introduce for the first time a permitted limit for particulate matter (PM) of 0.7g/kWh for engines of up to 85kW (114hp) and 0.4g/1Wh for engines of more than 85kW. The big engine level is regarded as tough by the manufacturers as they are having to meet a stringent level in one go, with two years' notice.

The term particulate matter (PM) covers both soluble and insoluble material which comes from the combustion of the fuel and the lubricating oil. Solids are typically carbon particles and ash, and the liquids include sulphates and nitrates in water.

The engines will have to be turbocharged and charge-cooled to meet these 1992/3 requirements. NOx content, in particular, increases as combustion temperature rises. Charge-cooling helps significantly as it reduces the temperature of the hot air delivered by the turbocharger. The lower the air temperature, the lower the NOx levels become and in this respect air-to-air charge-coolers outperform air-to-water designs.

But the Green legislators are not stopping at stage two. Stage three is already more than a gleam in the European Council's eye and in October 1996 the permitted limits for CO, NOx and PM are set for further reduction. It is proposed to reduce CO by a further 11%, NOx by 22% and particulates by up to 50%.

PM could be set as low as 0.20g/kWh; the council will make the figure known in September 1994. Engineers will have to completely re-evaluate the diesel to reach these levels and substantially re-design the injection and combustion system, for example. Turbochargers, charge-coolers, four valves per cylinder, unit injectors and electronic injection control will become essential rather than a nice bonus.

Features such as variable geometry turbochargers could also be in the frame. That being the case, the engineers might have to resort to less elegant bolt-on solutions — particulate traps.

As the name suggests, these trap the particulate material in a ceramic filter and store it until it can be burned off. Trap technology, however, is not new. Some manufacturers have already gained valuable experience with them over two years with city bus operation.

There will be a pay-off to the operator as the engine is likely to be "sealed-forlife" and almost guaranteed to operate trouble free for half a million miles. By 1996, it is likely that the engine electronics will be integrated with the anti-lock/ anti-spin brake electronics and air cond

itioning/heating climate control electronics into a diagnostic system which dictates when the vehicle needs servicing. This "service when it needs it" approach should be much more time-efficient than today's "do it whether it needs it or not" approach. And it should reduce servicing costs.

QUIETER VEHICLES

Apart from meeting the emissions requirements, and developing a whole new generation of electronic controls and the associated diagnostics, the engineers are also faced with producing ever quieter vehicles. New legislation comes into effect in the UK this autumn but already the politicians have their eyes on 1996 and are looking for further reductions.

Vehicles with engines of up to 150kW could have to meet 80dB(A). At this level the engine ceases to be the major noise source as the biggest contribution comes from the tyres. These very quiet engines will not just happen, they will have to be developed and tested over a period of some years. This research will have a price and operators might be reluctant to pay the full cost, with the result that the new Green trucks will not come into use as quickly as the Government would like.

The politicians will have to face the possibility of offering subsidies if they want to see these expensive new environmentallyfriendly trucks replacing the older designs in a sensible timescale.

The good news is that in the five years until 1996 politicians and engineers and any other interested parties should have sufficient time to agree on a realistic approach which can be part of a wider, more global approach.

By Gibb Grace: regulations and environment manager at Iveco Ford Truck and former technical editor of Commercial Motor.