Some pundits rate the Mercedes-Benz 1733 as the best tractive

Page 38

Page 40

Page 41

Page 42

Page 43

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

unit in Europe. But whether UK operators are ready to accept the sophisticated Powerliner electronics, only time will tell.

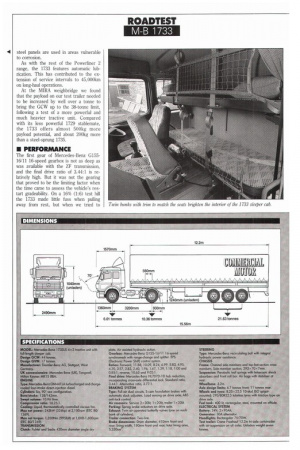

• The latest addition to the MercedesBenz range, the 1733, has been rated by some pundits as the best tractive unit in Europe. CM is not given to hyperbole but, considering its payload, journey time, fuel consumption and specification, we certainly agree that it has a lot going for it. Mercedes is confident enough to predict that in time the 1733 will account for 70% of all M-B tractor sales.

The last Mercedes-Benz tractor to be offered with a vee-configuration engine rated at 246kW (330hp) was the 1633 in the early eighties. The engine in question was the turbocharged 14.62-litre eightcylinder 0M422.

The same block in naturally aspirated form is still used in the current 1729 Powerliner, albeit with a slightly larger bore. Since then, however, Merc's engine technology has moved on a pace or two.

MDRIVELINE

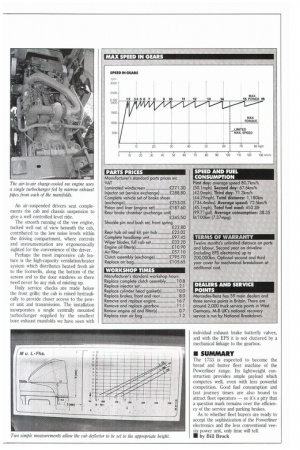

The 1733's 10.96-litre 0M44LA engine comes from the same family, with the original bore and stroke in a 90° vee configuration with individual cylinder heads. Helped by air-to-air charge-cooling it produces the same power output as the old 1633, with slightly less torque, but over a much wider rev band — and all with two fewer cylinders.

Vee-six engines are not renowned for their smooth running. Mercedes-Benz's solution was to redesign the crankshaft

with 300 offset crank throws, effectively equalising the firing intervals. The lighter vee-six engines are also claimed to be stronger than conventional in-line units, and this layout is popular on the Continent, but it has yet to win general acceptance with British operators.

In any case, its compact dimensions allow it to be installed forward of the steering axle. Its light construction also maximises potential payload, allowing the close coupling between the tractive unit and the trailer that is essential to fuelefficient operation.

To ram home the 1733's weight advantage, the chassis is made of high-grade steel. This allows its depth and thickness to be reduced; the fish-belly shape ensures that weight is added only where extra strength is needed.

Its front axle is uprated to 6.7 tonnes while a lighter (11-tonne) hub-reduction axle is used than on the earlier model. It incorporates a faster final drive and airsuspension as standard.

Mercedes has developed its own 16speed range-change transmission, designed from the outset to suit the EPS (Electronic Power Shift), which is standard on most Powerline tractive units. As a result Mercedes-Benz no longer has to rely on the services of ZF's 16-speed Ecosplit box. The Mercedes box and EPS combine to give smoother, faster gear selection and a short additional movement of the gear selection switch, gives more positive proof of engagement. Nonetheless, the quirks of electronic controls still leave something to be achieved in terms of reliability. More on that later.

The rounded, non-aggressive Mercedes-Benz cab profile may look the same as for earlier models, but individual panel pressings have been modified to ease assembly and strengthen its construction. Detail changes in the window line and the area around the windscreen now follow the corporate styling trend seen in Mercedes' entire CV range. Weight reduction remains high on the list of priorities, and plastic is used in non load bearing areas. Galvanised coated steel panels are used in areas vulnerable to corrosion.

As with the rest of the Powerliner 2 range, the 1733 features automatic lubrication. This has contributed to the extension of service intervals to 45,000km on long-haul operations.

At the MIRA weighbridge we found that the payload on our test trailer needed to be increased by well over a tonne to bring the GCW up to the 38-tonne limit, following a test of a more powerful and much heavier tractive unit. Compared with its less powerful 1729 stablemate, the 1733 offers almost 500kg more payload potential, and about 200kg more than a steel-sprung 1735.

• PERFORMANCE

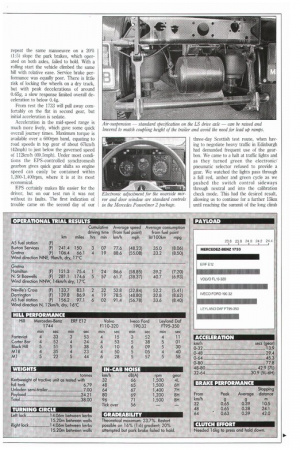

The first gear of Mercedes-Benz G15516/11 16-speed gearbox is not as deep as was available with the ZF transmission, and the final drive ratio of 3.44:1 is relatively high. But it was not the gearing that proved to be the limiting factor when the time came to assess the vehicle's restart gradeability. On a 16% (1:6) test hill the 1733 made little fuss when pulling away from rest, but when we tried to repeat the same manoeuvre on a 20% (1:5) slope the park brakes, which operated on both axles, failed to hold. With a rolling start the vehicle climbed the same hill with relative ease. Service brake performance was equally poor. There is little risk of locking the wheels on a dry track, but with peak decelerations of around 0.65g, a slow response limited overall deceleration to below 0.4g.

From rest the 1733 will pull away comfortably on the flat in second gear, but initial acceleration is sedate.

Acceleration in the mid-speed range is much more lively, which gave some quick overall journey times. Maximum torque is available over a 600rpm band, equating to road speeds in top gear of about 671mith (42mph) to just below the governed speed of 112kmih (69.5mph). Under most conditions the EPS-controlled synchromesh gearbox gives quick gear shifts so engine speed can easily be contained within 1,200-1,400rpm, where it is at its most economical.

EPS certainly makes life easier for the driver, but on our test run it was not without its faults. The first indication of trouble came on the second day of our

three-day Scottish test route, when having to negotiate heavy traffic in Edinburgh had demanded frequent use of the gearbox. We came to a halt at traffic lights and as they turned green the electronic/ pneumatic selector refused to provide a gear. We watched the lights pass through a full red, amber and green cycle as we pushed the switch control sideways through neutral and into the calibration check mode. This had the desired result, allowing us to continue for a further 151un until reaching the summit of the long climb

out of Dalkeith. At this point the trailing line of traffic probably thought our diversion into a convenient layby was made out of consideration to them.

Not a bit of it. On an instruction to change up, the EPS had once more found neutral and persisted in blocking a gear selection.

Using the check mode again provided the solution and we were soon on our way with little time lost.

The first two hours travel on day three of our artic test route take in some of the toughest hill climbs in Britain. For the first hour the EPS worked impeccably, giving fast, predictable changes; so quick that we were able to make down shifts using each ratio in turn, or in blocks of two as climbing conditions dictated, then where practical using the splitter for upward changes and accelerating through the box with equal ease.

Only when passing through the rangechange did gear engagement cause a slight delay and all went well until the approach to the hairpin bend at Shotley Bridge in Durham where we were baulked by oncoming traffic.

Having stopped we found ourselves gearless yet again for several minutes until moving the splitter switch luckily returned the control to normal.

Soon after, on the last and eversteepening stage of the aptly named Black Hill, we encountered more problems which all but brought us to a standstill until we were saved by the system selecting first.

Over the final 300km the transmission control worked without a hitch. When EPS works it is very good, but if it fails the vehicle is left stranded except for an emergency control that will select a low gear to move it to a parking spot.

• CAB COMFORT

The Mercedes-Benz L cab is slightly narrower than the full width of the vehicle but is well equipped. Twin bunks are supplied with side nets; not to prevent the driver from falling out while asleep, but to restrain items of luggage under heavy breaking during day time use. An air-suspended drivers seat complements the cab and chassis suspension to give a well controlled level ride.

The smooth running of the vee engine, tucked well out of view beneath the cab, contributed to the low noise levels within the driving compartment, where controls and instrumentation are ergonomically sighted for the convenience of the driver.

Perhaps the most impressive cab feature is the high-capacity ventilation/heater system which distributes heated fresh air to the footwells, along the bottom of the screen and to the door windows so there need never be any risk of misting up.

Daily service checks are made below the front grille; the cab is raised hydraulically to provide closer access to the power unit and transmission. The installation incorporates a single centrally mounted turbocharger supplied by the smallest bore exhaust manifolds we have seen with individual exhaust brake butterfly valves, and with the EPS it is not cluttered by a mechanical Linkage to the gearbox.

• SUMMARY

The 1733 is expected to become the bread and butter fleet machine of the Powerliner range. Its lightweight construction provides ample payload which competes well, even with less powerful competition. Good fuel consumption and fast journey times are also bound to attract fleet operators — so it's a pity that a question mark remains over the efficiency of the service and parking brakes.

As to whether fleet buyers are ready to accept the sophistication of the Powerliner electronics and the less conventional veesix power unit, only time will tell. • by Bill Brock