NOW IRE POWER!

Page 58

Page 59

Page 60

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

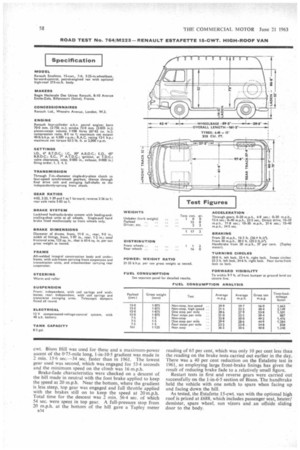

WHEN I tested the original 10/12-cwt.. version of the Renault Estafette early in 1961 (a test report appeared in The Commercial Motor of March 10, 1961) I was surprised by the excellent performance put up by the 845-c.c. engine fitted in that model, particularly as the van had a gross laden weight of almost 1 ton 17 cwt.— an overload of some 3-75 cwt. So it is not surprising that the 15-cwt. version, which is powered by a 1,108 c.c. engine producing 45 per cent more power and giving a maximum torque some 32 per cent higher than the original unit, should give, when running at a gross load only 2.cvvt. greater, a much better all-round performance.

The 15-cwt. version was introduced on June 29, 1962, although it was not generally available until about the time of the Commercial Motor Show last year. With the increased load capacity and engine change, minor changes were also made to other items in the mechanical specification of the model. These included a new, split casing for the gearbox which is still a four-speed, all-synchromesh unit but with ratios of 4-02, 2.25, 1-39 and 1 to 1, compared with 4-4, 2-59, 1.55 and I to I for the previous box. The engine is mounted as a unit with the differential and gearbox, the drive to the gearbox going through the differential casing. This layout is unchanged, but the drive to the front wheels incorporates a new constant-velocity joint at the Outer ends of the drive shafts. There are Repusseau rubbersleeved joints inboard of these to absorb torsional vibration and at the inner ends are extensible needle-roller knuckle joints.

The engine cooling system is sealed on the latest version, an expansion chamber replacing the usual header tank, and the system, which is filled with a water/glycol mixture to give protection against freezing down to —40°C., never requires topping up. Resultant on the increased weight rating, heavier rear springs are fitted and the size of the brakes on the front wheels is increased from 9-in, diameter by 1-77-in, wide to 11-in, diameter by 1-97 in. wide. Pressure to the front-wheel hydraulic-brake cylinders is now limited to 711 p.s.i. to prevent wheel locking under fierce application.

So far as driving the Estafette goes, the increased power available makes for an improvement, particularly in heavy 832 traffic conditions where it is more easy to keep up with other vehicles than was the case with the smaller engine. The seating is comfortable and the driving position good, all controls being easy to reach and, apart from the flashingindicator operating arm (located on the right-hand side of the steering column) which seemed too easily to return to the neutral position, work effectively.

From the point of driving comfort I would say that the Estafette has few equals, As an illustration of this, I drove the van 420 miles in one day during the period of the tests without feeling excessively tired at the end of it. I can think of few vans or even cars that I have driven in which this would have been the case.

Heating and ventilation on the Estafette are very good. The heater is a standard fitting and its output can be controlled accurately. I found by using the booster fan it was possible to keep the windscreen effectively clear of mist even when the engine coolant was cold. One really excellent feature of the van, which is common to others of Continental origin, is the excellent lighting. The headlights were extremely powerful and well aimed and, more important, the dipped headlights, although showing a very useful light to the front—adequate for driving at over 50 m.p.h.—had a very sharp horizontal cut-off which prevented them causing a nuisance to on-coming traffic. The dipped beam was asymmetrical, showing more light on the kerb side, and it was a pleasure to drive in built-up areas at night using dipped lights (which 1 feel is preferable to sides only from the point of view of safety) without having everyone coming towards me putting their headlights on as a complaint against my causing glare.

The Estafette supplied by Renault was tested three times in all because of a defect in the brake system. On the first test there was also something wrong with the clutch operation, which caused the clutch to slip once or twice when maximum torque was being put through it. The unit is cable operated and it was found that the cable was sticking in its outer covering. When this was put right, there was no further trouble. However, the clutch fitted in the 15-cwt. is apparently identical with that employed whenthe 845-c.c. engine was fitted, although the 1,108-c.c. unit produces something like a third more torque. It was stressed by Renault that the clutch design was fully adequate for the torque the bigger engine produces but the fact was that a fairly small fault had produced slipping. Possibly the fault is an inadequately strong return spring for the pedal. The clutch pedal was very light even after the sticking cable had been put right and it could stand a stronger spring.

There was obviously something wrong with the braking system on the first test. Pedal effort required for normal braking was unduly heavy and the efficiency appeared fairly low. Maximum-pressure braking stops confirmed this when 46.1 ft. was required to come to a stop from 30 m.p.h. and 19.4 ft. from 20 m.p.h, On all the stops the front tyres marked the road heavily and, in the case of the stops from the higher speed, both front wheels locked. The rear brakes were doing very little work and, as on the 1961 test of the I0/12-cwt. van, which was only 2 cwt. lighter, stopping distances of 14.1 from 20 and 38.5 ft. frbm 30 m.p.h. were obtained, there was no doubt that the larger front brakes were getting the same pressure as the rear ones and the limiting device was not working, Renault found this to be the case on inspection after the test, and on the second braking test it was thought that a new limiting valve had been fitted. That this was not the case was shown on the tests when almost identical figures to the first runs were obtained. There had been some confusion over the fitting of the new partand, when this was eventually done, the brake figures of 38.5 ft. from 30 m.p.h. and 16.3 ft. from 20 m.p.h., as recorded in the panel, were obtained. The whole feel of the brakes was greatly improved; the pedal was still a little hard but not excessively so. Tapley meter readings for maximum deceleration were 75 per cent from both 20 and 30 m.p.h. on the initial tests, and it is interesting that on the final tests the figure from 20 was the same, whilst from 30 the maximum deceleration recorded was 70 per cent. This shows the limitations of taking deceleration-meter readings as a sole indication of braking efficiency!

Fuel consumption tests were carried out on A6 between Barton and Cloph ill, the 'frequently used route which gives a 6-mile out-and-return run, Figures obtained were very little different from those with the 10/12-cwt. model. In fact the 15-cwt. was between 0.4 and 0.9 m.p.g, better on the fully laden runs, whilst the position was reversed for the part-laden runs when the 10/12-cwt. was between 0-1 and 0.9 m.p.g. better.

High-speed fuel-consumption figures were obtained on a run up and down MI motorway between the A505 and A4I47 junctions. The figures quoted include a short distance travelled getting on and off the motorway at both ends and, whilst on the motorway, the van was kept at or near its top speed of 61 m.p.h. for the whole time. This figure for maximum speed takes into account a speedometer inaccuracy of 4 per cent. This inaccuracy, incidentally, was constant throughout the speed range. Fitting the larger engine, therefore, had no adverse effect on fuel consumption. But there was an appreciable improvement in the performance as is shown by the figures obtained during acceleration tests.

On the hill-performance tests the 15-cwt. also put up a much better performance than the smaller-engined 10/12

cwt. Bison Hill was used for these and a maximum-power ascent of the 0-75-mile long, l-in-10-5 gradient was made in 2 min. 15-6 sec.-34 sec. faster than in 1961. The lowest gear used was second, which was engaged for 53-4 seconds and the minimum speed on the climb was 16 m.p.h. Brake-fade characteristics were checked on a descent of the hill made in neutral with the foot brake applied to keep the speed at 20 m.p.h. Near the bottom, where the gradient is less steep, top gear was engaged and full throttle applied with the brakes still on to keep the speed at 20 m.p.h. Total time for the descent was 2 min. 56-4 sec. of which 54 sec. were spent in top gear. A full-pressure stop from 20 m.p.h. at the bottom of the hill gave a Tapley meter

a34 reading of 65 per cent, which was only 10 per cent less than the reading on the brake tests carried out earlier in the day. There was a 40 per cent reduction on the Estafette test in 1961, so employing large front-brake linings has given the result of reducing brake fade to a relatively small figure.

Restart tests in first and reverse gears were carried out successfully on the 1-in-6-5 section of Bison. The handbrake held the vehicle with one notch to spare when facing up and facing down the hill.

As tested, the Estafette 15-cwt. van with the optional high roof is priced at £688, which includes passenger seat, heater/ demister, spare wheel, sun vizors and an offside sliding door to the body.