COMING DOWN TO EARTH

Page 35

Page 36

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

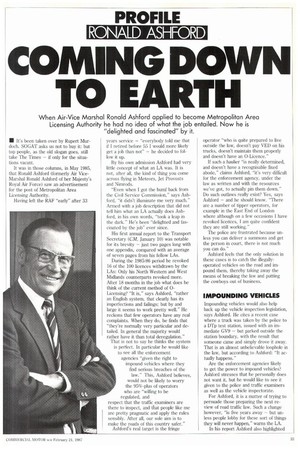

When Air-Vice Marshal Ronald Ashford applied to become Metropolitan Licensing Authority he had no idea of what the job entailed. Now he "delighted and fascinated" by it.

El It's been taken over by Rupert Murdoch. SOGAT asks us not to buy it: but top people, as the old slogan goes, still take The Times — if only for the situations vacant.

It was in those columns, in May 1985, that Ronald Ashford (formerly Air ViceMarshal Ronald Ashford of her Majesty's Royal Air Force) saw an advertisement for the post of Metropolitan Area Licensing Authority.

Having left the RAF "early" after 33 years service — "everybody told me that if I retired before 55 I would more likely get a job than not" — he decided to follow it up.

By his own admission Ashford had very little concept of what an LA was. It is not, after all, the kind of thing you come across flying in Meteors, Jet Provosts and Nimrods.

"Even when I got the bumf back from the Civil Service Commission," says Ashford, -it didn't illuminate me very much." Armed with a job description that did not tell him what an LA actually does Ashford, in his own words, "took a leap in the dark." He's been "delighted and fascinated by the job" ever since.

His first annual report to the Transport Secretary (CM, January 10) was notable for its brevity — just two pages long with one appendix, compared with an average of seven pages from his fellow LAs.

During the 1985/86 period he revoked 16 of the 100 licences withdrawn by the LAs: Only his North Western and West Midlands counterparts revoked more. After 18 months in the job what does he think of the current method of 0Licensing? "It is," says Ashford, "rather an English system, that clearly has its imperfections and failings; but by and large it seems to work pretty well." He reckons that few operators have any real complaints. When they do, he finds that "they're normally very particular and detailed. In general the majority would rather have it than total deregulation."

That is not to say he thinks the system is perfect. In particular he would like to see all the enforcement agencies "given the right to impound vehicles where they find serious breaches of the law," This, Ashford believes, would not be likely to worry the 95%-plus of operators who are "willing to be regulated, and respect that the traffic examiners are there to inspect, and that people like me are pretty pragmatic and apply the rules sensibly. After all, our sole aim is to make the roads of this country safer."

Ashford's real target is the fringe operator "who is quite prepared to live outside the law, doesn't pay VED on his trucks, doesn't maintain them properly and doesn't have an 0-Licence."

If such a haulier "is really determined, and doesn't have a recognisable fixed abode," claims Ashford, "it's very difficult for the enforcement agency, under the law as written and with the resources we've got, to actually pin them down." Do such outlaws really exist? Yes, says Ashford — and he should know. "There are a number of tipper operators, for example in the East End of London where although on a few occasions I have revoked licences, I am quite confident they are still working."

The police are frustrated because unless you can deliver a summons and get the person in court, there is not much you can do."

Ashford feels that the only solution in these cases is to catch the illegallyoperated vehicles on the road and impound them, thereby taking away the means of breaking the law and putting the cowboys out of business.

IMPOUNDING VEHICLES

Impounding vehicles would also help back up the vehicle inspection legislation, says Ashford. Ile cites a recent case where a truck was taken by the police to a DTp test station, issued with an immediate GV9 — but parked outside the station boundary, with the result that someone came and simply drove it away. That is an almost unbelievable loophole in the law, but according to Ashford: "It actually happens."

Are the enforcement agencies likely to get the power to impound vehicles? Ashford stresses that he personally does not want it, but he would like to see it given to the police and traffic examiners as well as the vehicle inspectorate.

For Ashford, it is a matter of trying to persuade those preparing the next review of road traffic law, Such a change however, "is five years away — but unless people lobby for these sort of things they will never happen," warns the LA.

In his report Ashford also highlighted problems with standards of maintenance. He accepts they are constantly improving, but asserts that maintenance is "not as professional as the industry would pretend, or indeed like. You've only got to look at the statistics on the number of vehicles that fail annual tests or spotchecks, which indicate that there are too many unroadworthy vehicles on the road." To quote his report, Ashford is "not impressed".

He says that the problem is all too frequently illustrated by those operators that appear before him on a section 69 disciplinary charge. Examiners regularly report that workshops are "filthy, dirty, scruffy, disorganised."

"It seems to me that often the responsible person — the director, partner, or manager — has not got a firm grip on maintenance. He is too busy organising schedules, selling his wares, without appredating that if he doesn't keep his maintenance right, it's going to be expensive, and he's not going to keep to his schedules."

First impressions are often very revealing when visiting a haulier's premises, says Ashford: "You've only got to walk round and you can almost smell whether the place is likely to produce a decent end product."

POOR MAINTENANCE

Poor maintenance is still the most common reason for operators in the Metropolitan area appearing before the LA on Section 69 charges.

The solution, says Ashford, lies in educating hauliers that "properly maintaining their vehicles has economic, as well as legal benefits. The industry can't afford to relax," If Ashford is uncompromising on maintenance, his views on overloading in the Met area are equally unequivocal: "There are really far too many overloaded vehicles." Of the 6,000 trucks spotweighed in his area during 1985/86, 19% were overloaded. Although Ashford accepts that the selection of these vehicles is anything but random, with examiners going for the `probables' rather than the `possibles', the results "are still too high".

He neatly sidesteps the argument for due diligence in overloading cases: "It's really a political matter which would involve a change in the law. It's for the politicians and the industry to sort out." He does, however, endeavour to use his discretion when deciding to prosecute.

"If we are convinced that the operator has done everything sensibly within his power to prevent an overload and the overload has resulted from negligence on the part of the driver, then we will only prosecute the driver — not the

company." During 1985/86 129,346 0-Licences were issued; down from 130,321 in the previous year. Of the former figure 17,434, were issued in the Metroplitan area. Ironically, far more licences were lost by hauliers ceasing trading than were revoked. So are the LAs making full use of their powers to ensure that newcomers are of sufficient standing? After all, the 925 operators which ceased trading last year presumably met those requirements when they gained their licences. Furthermore, with only 100 licences revoked, are the LAs tough enough with errant operators already in the business?

The power to revoke a licence "is not something that should be used lightly," says Ashford. "I revoked 16: 1 would have thought that was a fair warning to operators in the Met area that I am not a soft touch.

"The fact that I haven't revoked more also indicates that I was pragmatic and didn't exercise my powers lightly. It's very easy to be harsh and brutal to everybody who steps over the line — there has to be a balance. I do revoke licences: I don't want to, but if the circumstances are sufficiently bad, I will."

Ashford is satisfied with the current CPC examination process, although he remains suspicious of some 'grandfather rights'. He sometimes finds that he is acting against an 0-Licence "when I really ought to be taking action against the CPC holder who has proved himself to be incompetent and unprofessional."

The power to ask a CPC holder to retake the exam would, says Ashford, "make many think again — we do it with pilots. It would make the odd transport manager more diligent if there was the threat of a retest."

Like most LAs, Ashford has seen the growing effect of environmental regulations on licensing. He feels many representors are now "more astute in making representations and at articulating their case." The problem is exacerbated in the London area where many long-established haulage yards have been developed around, or are in areas that have been 'upgraded'.

"Councils are not very good at finding suitable operating centres — particularly for the small chap trying to start up a business." Ashford feels councils could pay more attention to this.

While seldom refusing a licence on environmental grounds, he does impose conditions on a number of licences "in order to mitigate damage to the environment" and feels that many hauliers could make a bigger effort to understand the often legitimate grievances of local residents. The extra effort, he says, often brings rewards.

The ability of the Metropolitan Area to issue licences is itself under threat. Ashford is having to deal with the problems caused by a 75% turnover in clerical staff, as many leave for higher paid jobs in the London area.

CONSTANT STRUGGLE

Despite managing to process virtually all applications during 1985/86, he admits that "it is going to be more difficult. It is a constant struggle to get licences issued on time."

Ashford maintains that the Dip could be more flexible in its attitude towards allowances for traffic examiners, particularly in the light of the current squeeze: "You can't run an enforcement system 9-to-5 Monday to Friday. We really ought to be out and about a bit more than we do at weekends and at night."

He brings a formidable degree of management experience to the job. In his own words he has been "in the decision making process for a number of years and I'm not frightened by having them reviewed." He also says it's up to others to judge whether his first year has been a success or a disaster. One thing is certain: for a man who spent half a lifetime with his head in the clouds, he is still very much down to earth.

by Brian Weatherley