Atkinson/York 42-ton-gross five-axle artic

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

The Custom Torque diesel is one of the more recent developments by Cummins and represents an interesting solution to the problem of getting improved performance from the vehicle without increasing engine size. The NHC-TC unit is based on the naturally-aspirated NH K250 and although both these engines have a bigger bore than the more well-known NH180 and 220 diesels they have exactly the same overall dimensions. The Custom Torque unit gives the same output of 240 bhp at the maximum speed of 2,100 rpm as the N1-1250. But turbocharging the engine increases the maximum torque output substantially—from 660 lb.ft. to 900 lb.ft. and moves the peak back from 1,500 to 1,200 rpm. At the same time the horse power is maintained at virtually a constant 240 bhp from 1,500 to the maximum governed speed of 2,100 rpm with a peak of 247 bhp at 1,800 rpm.

Impression of power

It is natural that this gives the effect of an engine having considerably more power. With a conventional diesel, 240 bhp at 1,500 rpm would suggest something approaching 350 bhp at 2,100 rpm and the intermediate figures are as important as the maximum for a vehicle does not spend the greater proportion of its life at maximum engine speed. The high power and torque at low engine speed were most beneficial in enabling the Atkinson to "hang on" to gradients and while it was normally better to make changes down at about 1,500 rpm it was satisfactory to let the engine go down to 1,200 rpm in certain circumstances. The unit certainly performed like an engine with a very much higher output and makes something of a nonsense of using power-toweight ratios as a means of comparing one vehicle with another.

The Fuller Roadranger 10-speed gearbox is a good design and has a very easy gear change action. It took a little time to get completely used to the very short stroke of the lever and one often felt that the new ratio could not be fully engaged; it usually was. With all the power coming from the engine all 10 ratios were rarely needed and except on the steeper gradients it was more convenient to make what Fuller calls "step changes", missing out alternate ratios.

Roadranger is a range-change with the five gears in the main of the box used in sequence with ixiliary ratio in use and then the ice repeated with "high" engaged. 3 advantage of a range-change box every gear change is positive. But if jeer is needed there is more marita1 required than with a splitter-type N. It is also easy to forget momenwhich auxiliary ratio is in use and his makes only one step out with a

one is five out with a range

connection between the engine learbox in the test vehicle was h a Lipe Rollway clutch. Operation clutch pedal is air assisted and this I extremely well, The system is Imple with an air chamber operat-. the linkage and actuated through a ilye fitted in the operating rod. The was no different to that of a norianual or hydraulic clutch and no N as evident. During the operational e had some trouble with a tight it the clutch pedal which frequently ited full engagement. This resulted lour being lost on the second leg of mrational trial in getting the bush !d—the job of replacing two grease s to types which matched the only ig equipment available was rather 3rd.

rest of the test vehicle followed the practice used by Atkinson on other designs. The rear bogie was a Kirkstall T.48 with double-drive axle and a lockable third differential. Braking was by a dual-circuit system with the rear-bogie brakes independent of the system for the front axle and semi-trailer connection. Lock actuators on the front and rearmost axle provided for parking but the secondary system employed only the front axle and the auxiliary connection to the semi-trailer. This, in my view, is not a satisfactory set-up as it puts the responsibility of providing too much of the secondary system on the trailer.

We were very fortunate in being able to complete the operational trial without a serious hitch as the weather both before and after the run was really bad and brought vehicles all over the country to a halt. As it turned out, the only snow that we met was on A68 from just before Carter Bar to the point that we turned off this road for Newcastle and some when on the final stretch of the motorway. The first part of the run up to Scotland was made in misty conditions and on wet roads but this did not slow our progress unduly. Cruising speed on the motorway was between 50 and 55 mph and on normal roads the limit of 40 mph was conformed with. An immediate impression when first taking over the wheel of the test vehicle was the excellent steering which was very light yet positive. It was necessary to exercise restraint on bends and keep the speed to a suitable level as it appeared possible that the double-drive bogie could "take over" and send the outfit straight on if too-harsh movement of the steering were to cause the front tyres to lose their grip.

When taking bends fast on the motorways in wet conditions there was a feeling similar to understeer in a car and there was one very difficult stretch on A5 where mud and grease on the road reduced adhesion to a low level and called for very delicate handling of the steering wheel.

As usual, the first fuel fill-up on the operational run was at the Forton Service Area on M6 which hadbeen reached in the total running time of less than 5hrs. The fuel consumption worked out at 5.9 mpg for the 207 miles from the Blue Star Garage at Hemel Hempstead. This was the best fuel figure obtained on the run and was followed by 5.4 mpg for the next 84 miles to Gretna including the climb of Shap. After M6 we had a very slow Jun almost to Kendal behind a very slowmoving mobile crane—it is not only cars that get held up—but after this a good average speed was put up.

Traffic after Kendal was fairly light but we caught up with some more slow trucks just as we were expecting to have a clear run up Shap. The Atkinson was badly baulked at the beginning of the main climb which brought the speed down to 4 mph and called for second gear. After going past the "obstruction", the speed increased quickly to 12 mph and fluctuated between this and 20 mph for the rest of the gradient, with 29 mph reached at the actual summit after the easier final part. At the Jungle Cafe, from which the climb was timed, the speed was 25 mph and the total time to the top was 11min 31sec.

The good stretch of A74 which begins not far beyond Gretna enabled 40 mph to be maintained continuously but after the turn onto A701 at Beattock progress was slow-it was dark and the twisting road was difficult for an outfit such as that being tested. In the circumstances a 26 mph average to Dalkeith was good.

On the second day, a stop to attend to the clutch was made in Jedburgh, this being considered urgent by then with a slight smell from the clutch indicating that trouble could be expected on the more severe country in front of us. We came to the first snow on the road shortly before Carter Bar and the whole of this 2-mile gradient was covered with a layer of compressed snow. Speed at the bottom of Carter Bar was 38 mph and most of the climb was made at around 15 mph in fourth gear. Thanks to the double-drive bogie there was no loss of adhesion although it was felt desirable when approaching the steepest 1-in-10 section to engage the differential lock just to make sure there would be no difficulty.

On the 1-in-10 section, speed dropped to 12 mph and a change down to third was needed but by the summit, a speed of 14 mph was attained; the total time for the climb was 8min 2.4sec.

Doubts about the ability of the outfit to manage the 1-in-5 gradient of Riding Mill and others almost as severe on the more difficult part of A68 had existed from the start of the run. But it was only made obvious that a detour from the usual route through Corbridge and Consett to Al would have to be made when we got to Ridsdale and when difficulty was experienced in getting over a gradient of about 1-in-6.

After consultation with a garage owner in the town, it was decided to make a turn for Newcastle at 86318, to go into the city and pick up Al there. With the transmission ratios employed the Atkinson did well on the hard part of A68 which we did cover and the average speeds of 25.4 and 26.6 mph confirm this. The fact that the outfit would not have been able to manage 1-in-5 is relevant only so far as it confirms what every operator must know-that a specification must be decided on which will allow a vehicle to cover any roads which it is likely to meet. The specification of the Atkinson was intended expressly for motorway and trunk-road operation and if it had been envisaged that the vehicle would have to be able to climb 1-in-5, various alternatives were available. A lower rear axle ratio, the direct-top version of the Fuller 10-speed box which gives a bottom ratio of 8,05 to 1 or the 15-speed Roadranger which is basically the same box but with an additional extra low range in the auxiliary section which gives a 12.0 to 1 bottom, could have been fitted.

The change of route increased the on the second day's run by only and after Newcastle the trip to iempstead was uneventful except :avy fall of snow (which did not a short distance beyond the r Forest Service Area. Average for the two days were similar and 34.4 mph—with the iverage 34.8 mph. These are very idable and so was the overall fuel ption of 5.23 mpg.

te of the length of the trip I was ssively tired at the end of it but I imber of aches and pains most of areas affected by the hardness of er's and passenger's seats. Both 'ilk' have done with softer bases Jigger squab for the passenger ave meant less moving about to ft comfortable. The front suspen)eared rather harsh and on some

"bouncing" of the front end ave been reduced if dampers had :ted. Some front-end "bounce" o induced by movement of the yid this coincided with particular speeds—mainly between 1,600 DO rpm depending on which gear 'aged and how much power was

leafing system was more than S in the near-freezing tempera'countered on the test and the were very good although they ip a lot of dirt. The vehicle itself

dirty during the run and a fair was left on the right-hand side of the driver's screen in the area not touched by his wiper. But this did not affect the visibility to any great extent; visibility was to a good standard.

Non-standard, coloured-Perspex visors were fitted on the test vehicle but I did not find these much use and as they laid horizontally, about level with the caboccupants' heads, when not in use they would be positively lethal in an accident.

Little heat from the engine entered the cab and the noise level inside the vehicle was reasonably low; that which there was caused no discomfort as it was a deep note and if anything quite pleasant.

The test vehicle was fitted with a Kysor shutter which had been found on tests carried out by Atkinson to give a fuel consumption improvement of about 0.25 mpg. A change in engine—or fan --noise when the shutter opened was quite noticeable and it was clear that the shutter was closed for the majority of the run. It was also noted that the temperature of the engine coolant was steady at Just over 80deg C (172 deg F} for most of the way.

The standard of cab interior on the test vehicle was, in my opinion, below that of the latest British designs, but nevertheless, the Atkinson was a pleasant vehicle to drive. As I have already said most of the controls were light and convenient. Exceptions were the secondary /park valve which required an awkward and heavy movement of the lever into the "parked" position and the accelerator treadle which was set rather "high" and caused an ache in the ankle. Adjustment to the control rod improved the accelerator but it was still far from perfect.

As well as the operational trial, brake-performance and acceleration figures were obtained—at the Motor Industry Research Association test ground at Nuneaton. The Atkinson gave a good account of itself on these and considering the results with those from the long run suggests that the model could be an important contender for a 42-ton-gross market if this ever comes about in this country.

THE NEED to design engines and vehicles ti provide optimum siting of electrical equip ment and for attention to important detail ii electrical installations was the theme of major part of the three-day course last wee on electrical equipment at Loughboroug: University of Technology. And many fore casts were heard that the University woull play an increasingly important part in th research projects of manufacturers and helping fleet operators. to sort out thel problems.

The course was the first to be organized b the University in conjunction with the RTITI and Mr. P. Haxby, the Board's director c training, said that he hoped the course woul be the precursor of many like it, covering variety of subjects.

After giving an evening talk on the factor affecting the design of electrical systems, M J. A. Cook, a director of the CAV compam said during the discussion that the Leylan 500 fixed-head engine was one of the firt units for many years that had been designe to give maximum reliability and that he hope other engine makers would follow Leyland' example. Mr. Cook was replying to a corr ment by Mr. V. J. Owen, chief engineer of th Trent Motor Traction Co., who pointed ot, that the Leyland 500 was the first example c an engine on which the alternator we installed in the right place, namely on top c the block, where it would not be splashed b salt-laden mud. For the most part, alternator were located in ridiculous positions. About 4 per cent of vehicle faults were electrica declared Mr. Owen, and many faults were i the "sillycategory. The standard of electr cians' skill was deteriorating and a new bree of electrical engineers was needed. Ther

• should be more co-operation between equip ment makers and vehicle builders.

Mr. Cook forecast that fully automati gearboxes would be increasingly employe and that the more complex equipment of th vehicle of the future might well include autt matic fault-finding units, improved lightin and long-life generators with a high-power-tc weight ratio. The turbocharger-driven higt speed alternator should be taken seriously.. unit of this type had been operated e) perimentally by CAV over the years, A 60am machine having the size of a packet of 2 cigarettes would cut-in at 18,000 rpm an run up to 85,000 rpm.

While embedding diodes in epoxy resi gave protection against salt water and so o (the use of cooling fins on the holder had bee discontinued because they trapped corrosiv foreign matter), employing a totally enclose alternator represented the only proper mear of protecting a unit mounted on an underfloc engine and the more extensive use of full enclosed units for this and other applicatior could be expected. Flexible circuits could L bent to any shape without impairing the operation. They were suitable for commercia vehicle applications but the relatively sm.8 quantities required (compared with circuits ft private cars increased their cost.

Asked by Mr. Cook to reply to a questic relating to batteries, ,Mr. F, Kay, CAV salt manager, forecast that eventually the leac acid battery would be superseded by different type; in the meantime, batteries di signed for charging by an alternator had th advantage that they could cope with surges the charging rate. Mr. Cook forecast thi better batteries would be produced becau they were needed for electric vehicles.

Asked to differentiate between reliabili. and long life with obsolescence in mind, M Cook said that ideally all equipment should L built to comply with a predetermined Ii factor, which was a very difficult exercise. M

cribed a question from Mr. E. J. works superintendent of Southend n Transport, as most difficult and Or. Hatchett wanted to know when I of electrical equipment would be and so enable spare parts to be lable. Later he observed that reduce of components was not necessariiive.

ik replied that CAV based obsolesi period of 15/18 years. Running an at high speed enabled a greater De obtained from a smaller unit. Air ould provide for a speed range of ) 30,000 rpm. Commenting on a that a 6V system had advantages and 24V systems, Mr. Cook said ompany would like to use higher vhich would ease the starting probler voltage would, however, involve fitting light bulbs with relatively flimsy filaments which would have a shorter life. A 48V system would not be very much more expensive than the lower-voltage types if it were produced in sufficient quantity.

In reply to a question from Mr. Haxby, Mr. Cook said that a competent electrician -could in many cases repair electrical equipment satisfactorily. CAV philosophy was based on the increasing use of replacement units because a factory-reconditioned unit was as good as new and incorporated any modifications that had been introduced. Moreover, it normally cast little more than the cost of repair.

As mentioned in last week's issue of Com mercial Motor, Mr. J. D. Britton of the electronics section of the LUT department of transport technology made a plea during a lecture on semi-conductor devices for a new

philosophy regarding improved methods of repairing electrical equipment. Tributes were paid to Mr. Britton's lecture by many of the post-graduate students attending the course.

Dealing with the ability of a diode to withstand high temperatures and voltages, Mr. Britton said that employing diodes that were suitable for arduous conditions presented an economic problem rather than a technical one. A diode could be destroyed by an excessively high temperature or voltage but failure did not change its appearance. Diodes were produced in very large quantities and were then graded according to intended use. Selection represented the expensive exercise in the production of diodes, a much larger number of low-voltage units than of the high-voltage type being produced in a batch. A high-grade diode could withstand temperatures up to 260deg C and could withstand enormous overloads up to 2,000amp for around 20 milli-seconds.

It was all important to provide good heat dissipation by proper attachment to the heat sink and it was imperative to avoid overheating by, for example, the use of a welding torch close to the alternator. Protection against polarity reversal could be provided by incorporating a Zener diode in the circuit. A faulty soldered joint could cause failure of a diode, In a general comment on electrical faults during an informal discussion, Mr. E. J. Hatchett, works superintendent of Southend Corporation Transport, complained that the average mgchanic didn't want to know about semi-conductors or how to test electronic equipment. The RTITB could do a very good job of work by organizing the training of workshop personnel, particularly in the case of electricians.

During a lecture on factors affecting the selection of electrical equipment, Mr. A. K. Allan, manager of export sales engineering. CAV, also mentioned the danger to diodes of very high inductive voltages. Faulty installation of electrical equipment on the part of bodybuilders could cause failure of electronic control equipment or result in its malfunctioning. For example the case could be cited of the semi-automatic gearbox that changed gear'when someone pressed a bell push.

Brushless alternators will eventually be produced for commercial use, Mr. Allan told a p.s.v, operator during the discussion. A prototype model had been tested and had run satisfactorily, but some outstanding control problems had still to be overcome, notably the elimination of output pulses. This could currently be done by employing a complex control system which was costly: the machine was simple and cheap.

There were dangers in prediction, added Mr. Allan. Development of the machine could be overtaken by events in the form of a new type having permanent magnets.

Asked by Mr. Owen whether more reliable electrical equipment could be made available if operators were willing to pay, say, 50 per cent more than the current price, Mr. Allan pointed out that a p.s.v, operator could specify the type of equipment he required. In support of Mr. Akan, Mr. Kay described the demand for more reliable land costly) equipment as a healthy sign. Producing a heavier-duty generator was relatively simple as exemplified by the totally enclosed AC 203 alternator. In contrast, the starter motor was a "highly complex beast" that could less easily be produced to give greater reliability, There was a lot to learn about starters.

In reply to another question, Mr. Allan claimed that diodes could withstand temperatures up to 150 /200deg C and that semiconductor control equipment could be used in the highest ambient temperatures normally encountered. In the case of a stationary engine operating in the desert, however, a specially modified older type of regulator should be used.

Elaborating on his earlier statement regarding starter motors in a lecture on electrical problems in service, Mr. Kay mentioned the inaccessibility of mounting bolts as the difficult problem that everyone tried to improve upon. Apart from other troubles, special tools were required to apply a predetermined tightening torque to the bolts.

Common installation faults cited by Mr. Kay included an out-of-mesh clearance that was too great or too small and incorrect alignment. The latter could be caused by out-of-line fixing bolts resulting, for example, from the use of coarse-threaded bolts for attachment to an aluminium-alloy member in place of bolts with a fine thread, which could be regarded as bad engineering practice.

Dealing with generator drives, Mr. Kay pointed out that the side load on the bearings of the machine was much greater if it were positioned between the engine pulley and the Ian pulley on the tight side than was the case if it were located on the slack side. If the fan and pump absorbed 11)hp an equivalent power was relayed through the generator pulley if it were mounted on the tight side; the Power relayed was reduced to 34/4 hp if the machine were located on the slack side and the side force was reduced proportionately with a corresponding increase in bearing life. CAV machines were designed with a factor of ,safety to cater for tight-side mounting.

A much longer bearing life would be provided if the fan pulley were driven by a separate belt, so that the generator drive was not used to operate any other equipment. Obtaining optimum bearing life also depended on reducing overhang to a minimum and the avoidance of misalignment. The correct angle of wrap was also important.

Less obvious environmental factors mentioned by Mr. Kay included flexing of an alternator, caused by vibration, which could result in an ingress of water and could be regarded as a major problem. Blocked louvres could cause overheating and mal-placed cables that allowed chafing was a common fault. Battery/starter cable length should be kept to a minimum and circuits should be arranged to avoid a voltage drop of more than 1V.

Requested for information regarding protection units, Mr. Kay emphasized that it was necessary to know the principle of a circuit before detailed advice could be given. A fast fuse could be fitted which broke the circuit so quickly that there was insufficient time for the high voltage to damage the diodes, A Zener diode in the appropriate place in a circuit absorbed the voltage surge and curtailed the voltage rise.

After making a plea for well informed and unemotional criticism, Mr. Kay suggested that the TM-A, RHA and other associations could form technical sub-committees which would make it their business to inspect and criticize new vehicles and to feed back information to the vehicle and equipment makers. "It seems to me," said Mr. Kay, —that we are moving towards the tighter specifications and heavier equipment that operators want".

During an informal general discussion on the course Mr. Kay declared that the LUT could play an important part in fostering progress in the transport industry. It was a big thing that the LUT and industry had joined hands. One of the fruits of the get-together could be a more thoughtful and realistic approach by all sides of the industry to the practical problems of optimum vehicle utilization.

Attack

Mr A. G. Plackett, product development engineer of Smiths Industries, was under fire from all sides during the discussion that followed his lecture on heating, ventilating and air-conditioning systems. Opening the attack, Mr. E. H. Wilkinson of the RTITB said that bus engines ran at too low a temperature for optimum efficiency unless the temperature was kept up by blanking off the radiator or by using a controlled fan. And Mr. H. H. G. Woollford, managing director and chief engineer of the Gosport and Fareham Omnibus Co., doubted whether there was any engine heat to spare for saloon heating in the case of double-deckers in cold weather even if these precautions were taken; measurements of sump temperatures had shown that the engines were running too cool. One of the few engineers on the course with an interest in goods vehicles, Mr. T. J. Goldrick, chief engineer of the Freight Transport Association, claimed that there was often notenough heat to keep the cab of a lorry warm.

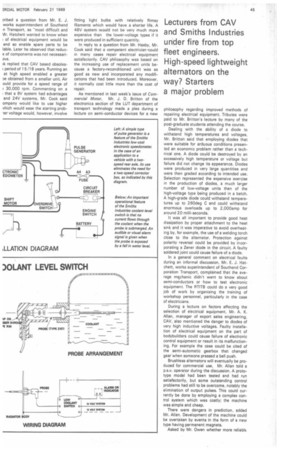

Special mention was made by Mr. Plackett in his lecture of his company's unitized automatic heater that was shown for the first time at Earls Court and is now undergoing field trials. One of these units would, he said, normally be adequate for the heating requirements of a double-decker bus in this country and it use greatly simplified installation. It took the place of four separate,heat exchanger units and was based on a large-capacity centrifugal fan with an output of around 700 cu.ft./min, high-capacity heat-exchanger and water-valve unit and three sensor units. It could be used to circulate fresh air or to recirculate air from the saloon and required a current supply of up to 40amp at 24V. A new type of high-output high-efficiency motor had been developed by the company that was of the permanent-magnet type and provided for power outputs up to 100W.

In an earlier lecture, Mr. W. W. Bischoff, chief engineer (instruments) of Smiths Industries, described the operating principles of the company's tachograph. This.is accurate to +3 per cent of the theoretical values over a temperature range of Odeg C to plus 40deg C and when vibrated up to a force of 0.5 g with a frequency of up to 100 cycles /sec. The instrument has an overall temperature operating range of —40deg C to + 80deg C.

Special mention was made by Mr. Bischoff of the Smiths electronic speedometer which incorporates a small pulse generator, is appreciably cheaper than the electric speedometer and is relatively simple. Mr. Bischoff forecast that an instrument would eventually be developed that would derive a speed signal direct from the road wheels by means of an inductive pick-up.

Other instruments mentioned by Mr. Bischoff included an instrument package for commercial vehicles of the printed-circuit type which has been introduced to match the tachograph installation. No technical details were available of an electronic coolant-level switch, the probe of which is mounted horizontally in the header tank. Mr. Bischoff stated that it had a particular virtue; when the probe was submerged no current was passed through the coolant which was a necessary requirement for its acceptance by engine makers. A coolant-level indicator had advantages over a warning device actuated by an increase in temperature above a enticel point because the warning given by the latter was often "too late".