with the past

Page 35

Page 36

Page 37

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

• It's hard to drive the subject of this week's roadtest without a sense of awe. This Leyland Lynx was one of a batch of 10 tankers bought by Esso in 1938. Now owned by Allan Lock, it is liveried in his dark blue coachwork, and is in splendid working order. Trundling along behind the wheel, one wonders what happened to the other nine, or indeed what happened to the drivers of those vehicle.

By 1938 Franco's insurgents had almost won the Spanish civil war, and while Neville Chamberlain had signed a deal with Hitler over Czechoslovakia, the British government was ordering Spitfires as fast as it could. It would be just over a year before those drivers were called up to fight, and the fuel oil carried in those little tankers was rationed.

Did those Esso drivers perish in World War Two? Or are they still alive, watching the Berlin Wall come down with wry smiles? Perhaps they remember the Esso tankers they once drove, and the innocent times before the turmoil of war.

The wartime and post-war history of Esso truck number 5473, registration FGP 980 (it lost its original number plate thanks to the policies oi the DV LC), is unknown. It seems fairly certain that it was commandeered for war work, and the shortage of vehicles after the war would have meant that it continued to endure hard service. Like most old commercials it was eventually retired when it became uneconomical to run, and was in danger of a one-way trip to the scrapyard when it was rescued by a friend of Lock. He sold it on in 1980 with a proviso that it was well cared for. The Leyland has since been stripped down and totally rebuilt.

It still has the original Aluminium Plant and Vessel (APV) 4,545-litre (1,000gallon) two-compartment aluminium tanker on the back, complete with cast alloy strap mounts. All the original Petrol Regulations features are still there, including the conduit-covered wiring, and the electrical master switch. The pumping gear is all present and correct too. The pump is mounted on the nearside and powered from the engine: a hand throttle controls the engine revs and pumping speed.

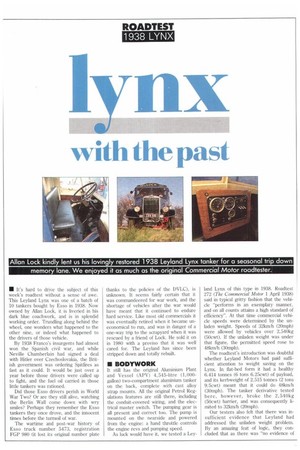

As luck would have it, we tested a Ley land Lynx oh this type in 1938. Roadtest 272 (The Commercial Motor 1 April 1938) said in typical gritty fashion that the vehicle "performs in an exemplary manner, and on all counts attains a high standard of efficiency". At that time commercial vehicle speeds were determined by the unladen weight. Speeds of 32km/h (20mph) were allowed by vehicles over 2,540kg (50cwt). If the unladen weight was under that figure, the permitted speed rose to 48km/h (30mph).

The roadtest's introduction was doubtful whether Leyland Motors had paid sufficient attention to weight saving on the Lynx. In flat-bed form it had a healthy 6.414 tonnes (6 tons 6.25cwt) of payload, and its kerbweight of 2.515 tonnes (2 tons 9.5cwt) meant that it could do 48km/h (30mph). The tanker derivative tested here, however, broke the 2,540kg (50cwt) barrier, and was consequently limited to 32km/h (20mph).

Our testers also felt that there was insufficient evidence that Leyland had addressed the unladen weight problem. By an amazing feat of logic, they concluded that as there was "no evidence of weight having been indiscreetly reduced, or of any engineering rule having been violated or even stretched", the truck was still a bit overweight. By reading between the lines one can see that while our testers would have liked to see some weight trimmed off the substantial chassis or the cab, what they were really looking for was a breakthrough in vehicle design. They would have to wait for the unitary construction cab for that breakthrough.

Apart from that rather unfair gripe, they liked the truck. Leyland had prepared for the test almost better than it does today. The Lynx was fitted with a fifth wheel, and a flow meter, so manual readings were superfluous. There is evidence of some spirited driving on the test, as the truck exhibited a "certain amount of sliding, with a suggestion of tail wag".

It is not necessary to switch your brain off to test Lock's truck. Spirited driving was one thing on the roads of 1938, hut Kent's crowded roads demand considerable aforethought when driving the Lynx. That said, we were impressed with the little 4x2's performance compared with its contemporaries.

The old Leyland six-pot OHV petrol unit starts easily, and the exhaust from its 4.7 litres does a fair bit of dust stirring on dry days. Unlike many of its petrol contemporaries the Leyland lump loses its revs quickly, which helps with gearchanges. It also has sufficient power to get the Lynx up to good speeds quickly, which helps on busy roads.

To engage first gear the truck has to be stationary when the 635rnm long gearlever can be notched into place. Raising the massive and very heavy clutch gets the vehicle rolling, but only just. Second gear must be found quickly before the engine runs out of revs (it is here that the engine's ability to lose revs quickly helps the driver). Double-declutching upwards is necessary of course, but for this change it is no more painful than the same process in a Ford Cargo.

Second is a big gear, which allows considerable headway to be gained. It is not long, however, before a change into the "silent third" ratio is required. The word "silent" in connection with third gear is obviously a use of the word with which we were previously unaccustomed. Meticulous care has to be observed when changing into and out of third gear both up and down the box. Lock assures us that this is normal, and that he has become used to it. We wouldn't mind betting he practices this change in his sleep to carry it off in the effortless manner he has.

By the time the change to fourth is needed the truck is doing around 40km/h (25mph). This is really travelling. The intake roar almost sucks children off the pavement, and one is frighteningly aware of the minimal capacity of the brakes. Taking care not to pull the gear lever straight through to fourth, the final change is executed. Once in fourth a prod on the throttle gets the little truck accelerating down the road once more. The heady speed of 48kiii/li (30mph) is soon reached. The cab vibrates, the truck plunges on even minor imperfections in the road, and steering the beast is getting to be a bit of a problem. An additional complication is the view out of the cab — one cannot see the front wheels or the front wings. Placing the vehicle on the road is work of considerable perplexity. It's no good, we'll have to slow down.

There are three braking systems on the Lynx: a foot brake which serves all four wheels, in a cursory fashion; a handbrake to serve the rear wheels through a mechanical linkage . . . and hope. In fact, a combination of the first two is adequate to slow progress, but not without a bead or two of sweat trickling down the brow. The handbrake is a push-on variety, which allows a mechanical advantage by dint of the driver bracing his back against the seat. It also means that when a driver is thrown forward by the massive deceleration, he will still he pushing the brake on. Sonic hope. Stopped at last there is chance to look round the inside of the cab. At 508mm (20in) in diameter, the steering wheel is almost as wide as the gearlever is long. The handbrake is placed to the right of the driver's seat, in such a position that it is impossible to get out of the cab without it engaged.

Three massive pedals lurk in the footwell, and their slots in the floor mean that bicycle clips are vital in wet weather. Instrumentation is rudimentary, but Smiths Instruments has provided a clock, speedometer, odometer, and oil pressure gauge. There are also massive switches for the ignition, starter, choke and lamps.

Most of the rest of the cream-coloured cab looks like the inside of a ship. The wooden spars have been screwed together with angle plates for strength. The floor is simple flat plywood, and above the opening windscreen is a single CAV windscreen wiper motor. There is a small opening hatch in the roof for ventilation, and quarter-light windows for a rear view.

The question on our lips was, of course, where does a driver keep his Vera Lynn tapes and packets of Wood

bines? The door pockets provide the answer, being copious and deep. We even discovered a packet of 20 Woodbines in one pocket. and thought it might have been a period accessory until Lock pulled out another packet of the things and offered them round.

The cab leaks air worse than a sieve, and impression of being a Jumbly is confirmed by a driving position suitable only for those of extremely limited stature. There is also a considerable amount of noise in the cab, and the wing mirrors are more suitable for lipstick application than viewing the rear of the truck.

Do we work as hard as those hauliers of the "good old days"? The Lynx needs its rockers checking once a week, and the engine has to be overhauled, with white This is how our predecessors portrayed the Leyland Lynx road test in The Commercial Motor, of I April 1938.

metal bearing that are hand-wiped. There are hundreds of grease nipples round the truck, and the tyres don't last too long either. Keeping the Lynx on the road demands a lot of work, but what about the driving?

Apart from a considerable resistance to the cold, a driver would have had to put up with the awful driving position, the heavy clutch, the crash gearbox, and the ride. Deliveries of fuel might have to be done with a churn; Lock still has the original in the back. It was a hard life, and no mistake.

At risk of being anthropomorphic, the old Lynx has seen some incredible things in its 52 years. Driving it today harks back to a simpler, guilleless existance, filled with the brooding foreboding of approaching war.

We can only thank Allan Lock for giving us a chance to stop and stare, and wish him and all our readers a merry Christmas and a happy New Year.

1=1 by Andrew English