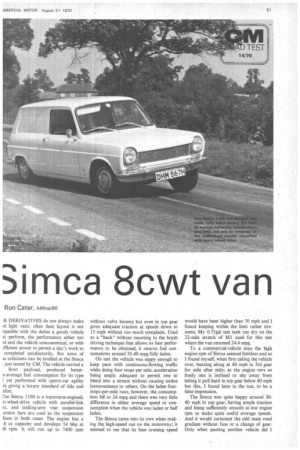

3imca 8cwt van

Page 53

Page 55

Page 56

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Ron Cater, AMInstBE R DERIVATIVES do not always make od light vans: often their layout is not npatible with the duties a goods vehicle st perform, the performance either too 'd and the vehicle uneconomical, or with ifficient power to permit a day's work to completed satisfactorily. But none of se criticisms can be levelled at the Simca just tested by CM. The vehicle carried a

8cwt payload, produced bettern-average fuel consumption for its type I yet performed with sports-car agility le giving a luxury standard of ride and rhe Simca 1100 is a transverse-engined, n-wheel-drive vehicle with parallel-link it, and trailing-arm rear suspension orsion bars are used as the suspension iium in both cases. The engine has a 8 cc capacity and develops 54 bhp at 10 rpm. It will run up to 7400 rpm

without valve bounce but even in top gear gives adequate traction at speeds down to 15 mph without too much complaint. Used as a "hack" without resorting to the brash driving technique that allows its best performance to be obtained, it returns fuel consumptions around 35-40 mpg fully laden.

On test the vehicle was nippy enough to keep pace with continuous-flowing traffic while doing four stops per mile, acceleration being amply adequate to permit one to blend into a stream without causing undue inconvenience to others. On the laden fourstops-per-mile runs, however, the consumption fell to 24 mpg and there was very little difference in either average speed or consumption when the vehicle was laden or half laden.

The Simca came into its own when making the high-speed run on the motorway; it seemed to me that its best cruising speed would have been higher than 70 mph and I found keeping within the limit rather tiresome. My 0.75ga1 test tank ran dry on the 22-mile stretch of MI used for this test where the van returned 24.4 mpg.

To a commercial-vehicle man the high engine rpm of Simca seemed limitless and so I found myself, when first taking the vehicle over, buzzing along at 40 mph in 3rd gear for mile after mile; as the engine revs so freely one is inclined to shy ' away from letting it pull hard in top gear below 40 mph but this, I found later in the test, to be a false impression.

The Simca was quite happy around 3040 mph in top gear, having ample traction and being sufficiently smooth at low engine rpm to make quite useful average speeds. And it would surmount the odd main road gradient without fuss or a change of gear. Only when passing another vehicle did I

need to drop a gear and let the busy 1100 cc engine have its head.

Steering

There was sufficient feel in the steering to permit complete control over the vehicle at all times. No special concentration on the steering was needed and neither did the Simca suffer from that common frontwheel-drive failing of needing extra power to prevent it wandering out of a turn. No matter what condition of load, there was no front-wheel-drive influence on corners.

Like other French-produced cars the Simca from which the 8cwt van is derived has been designed to take pave and other bad road surfaces in its stride. But unlike some other makes, the Simca suspension is neither complicated nor vulnerable, yet it remains more than adequate for the very worst road conditions. It suffered no excessive degree of deflection when fully laden, neither did it allow the vehicle to yaw and roll about when negotiating a twisting road.

One great advantage of the suspension is that it can be adjusted for normal conditions of load. That is to say if, for instance, the vehicle is to be heavily laden with goods for most of its working day the torsion bars can be wound up to stiffen the suspension. This is a job that requires either a lift or a pit and tools, and so it cannot be done as loads are changed. Frankly, I used the vehicle with the suspension in the standard torsiop-bar position and could not fault it at all, and I would consider that only overloading would warrant alteration of the setting.

During the maximum speeds-in-gears test the vehicle proved able to exceed the maximum motorway limit of 70 mph in third gear. On each occasion the maximum speeds were read at the commencement of valve bounce.

Acceleration results-as can be seen from the results panel-were excellent, but the high final-drive ratio rather limited the vehicle's hill-starting ability. On the 1 in 6.5 steepest section of Bison Hill the elutch needed punishing in order to make a reverse start and I only just managed a forward start without resorting to unorthodox methods. So lively is the power unit, however, that Bison was climbed in only lmin. I6.4sec. in second gear. The lowest speed recorded was 45 mph.

Throughout the test the vehicle proved thoroughly relaxing to drive, its seating being excellent if a little "sweaty". The steering was a little on the heavy side for manoeuvring and might prove a bit tiring ton woman driver using it in very congested conditions. But the layout of controls and the low pedal efforts required when using clutch and brakes more than compensated for this.

I found the cancelling device on the trafficators a little too "efficient"-the slightest movement of the wheel against the direction of turn cancelled the flasher.

Brakes

Brakes-discs on the front wheels and drums on the rears-proved more than adequate for the vehicle fully laden. There was evidence of more fade than usual after

coasting Bison against the brakes but recuperation was extremely rapid with complete restoration in only 0.75 miles at 30 mph being achieved. Full brake test results can be seen in the test panel.

Load space in the Simca amounts to 55 cu.ft. An expanded metal bulkhead is fitted between the driver and load space and this can be removed if required. The rear of the vehicle is closed by a lifting tailgate, counterbalanced to hold it in the raised position_ The catch for this door is of the pressbutton type and I would have preferred to see a positive twisting handle in its place for after 5,000 miles at the time of the test it had already become faulty.

Rounded wheel-arches protrude into the load space and poking through these are the tops of the rear dampers covered by neoprene rubber seals. These could, I think, prove vulnerable in service and I feel the rubbers should be replaced with metal caps.

The floor of the vehicle is a substantial pressing swaged to provide adequate stiffness for distributed loads. But it may not withstand very much concentrated loading and would benefit with a covering of thick plywood or a similar material.

With its moderate thirst for fuel and a 9gal fuel tank the Simca has a useful range of about 300 miles and it is comfortable enough for a driver to do that distance without undue fatigue.

From the workshop point of view the Sitrica is an accessible vehicle except for the oil filter which, although being of the bodiless type, calls for some contortions by the fitter trying to get at it. The vehicle does not employ a belt-driven fan; a thermostatically controlled electric fan serves the more than adequate semi-sealed cooling system—it ran only once during the test even though ambient temperature was 27°C (80°F).

Standard equipment on the vehicle includes seat belts, spare wheel, jack and tools, two-speed wipers, rubber mats, steering lock and heater/demister. Plated bumpers and several different colours of finished paintwork are also standard. Other units available as optional extras include a brake servo and radio.

As tested the Simca 1100 8cwt van costs £599.