Seddon Gives 8.7 m.p.g. at 3U Tons Gross

Page 50

Page 51

Page 52

Page 55

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Seddon-Dyson Articulated Outfit Returns Good Fuel Figure Over Difficult Course : Cummins Oil Engine Gives Rapid Acceleration and Fast Hill Climbing

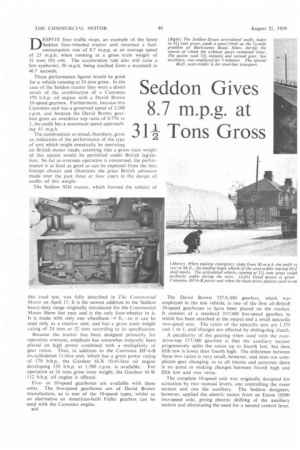

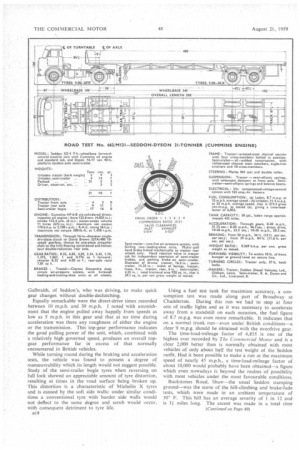

By John F. Moon, A.M.I.R.T.E. DESPITE four traffic stops, an example of the latest Seddon four-wheeled tractor unit returned a fuelconsumption rate of 8.7 m.p.g. at an average speed of 25 m.p.h. when running at a gross train weight of 31 .tons 101 cwt. The acceleration rate also will raise a few eyebrows, 30 m.p.h. being reached from a standstill in 46.7 seconds.

These performance figures would be good for a vehicle running at 24 tons gross. In the case of the Seddon tractor they were a direct result of the combination of a Cummins 170 b.h.p. oil engine with a David Brown 10-speed gearbox. Furthermore, because this Cummins unit has a governed speed of 2,100 r.p.m. and because the David Brown gearbox gives an overdrive top ratio of 0.776 to 1, the outfit has a maximum speed approaching 45 m.p.h.

The combination as tested, therefore, gives an indication of the performance of the type of unit which might eventually be operating on British motor roads, assuming that a gross train weight of this nature would be permitted under British legislation. So far as overseas operation is concerned, the performance is at least as good as can be expected from the best foreign chassis and illustrates the great British advances made over the past three or four years in the design of outfits of this weight.

The Seddon SD4 tractor, which formed the subject of

this road test, was fully described in The Commercial Motor on April 17. It is the newest addition to the Seddon heavy-duty range originally introduced for the Commercial Motor Show last year and is the only four-wheeler in it. It is made with only one wheelbase-9 ft.—so it can be used only as a tractive unit, and has a gross train weight rating of 24 tons or 32 tons according to its specification.

Because the tractor has been designed primarily for operation overseas, emphasis has somewhat naturally been placed on high power combined with a multiplicity of gear ratios. Thus, in addition to the Cummins HF-6-B six-cylindered 11-litre unit, which has a gross power rating of 178 b.h.p., the Ga-rdner 6LX 10.45-litre oil engine developing 150 b.h.p. at 1,700 r.p.m. is available. For operation at 24 tons gross train weight, the Gardner 61.W 112 b.h.p. oil engine is offered.

Fiveor 10-speed gearboxes are available with these units. The five-speed gearboxes are of David Brown manufacture, as is one of the 10-speed types, whilst as an alternative an American-built Fuller gearbox can be used with the Cummins engine.

B16

The David Brown 557A/480 gearbox. which was employed in the test vehicle, is one of the first all-British 10-speed gearboxes to have been placed on the market. It consists of a standard 557/480 five-speed gearbox to which has been attached at the output end a small epicyclic two-speed unit. The ratios of the epicyclic unit are 1.375 and 1 to 1, and changes are effected by sliding-dog clutch.

A peculiarity of the gearing when used with the overdrive-top 557/480 gearbox is that the auxiliary section progressively splits the ratios up to fourth low, but then fifth low is lower than fourth high. The difference between these two ratios is very small, however, and does not complicate gear changing, as to all intents and purposes there is no point in making changes between fourth high and fifth low and vice versa.

The complete 10-speed unit was originally designed for actuation by two manual levers, one controlling the main section and one the auxiliary. The Seddon designers. however, applied the electric motor from an Eaton 18500 two-speed axle, giving electric shifting of the auxiliary section and eliminating the need for a second control lever. • export purposes at 32 tons gross a heavy-duty e-reduction axle with spiral-bevel primary gearing louble-helical secondary gearing is available. This load rating of 13 tons, but for less arduous duty tons, or. in special circumstances, even at 32 tons train weight, a 9-ton double-reduction axle can be ed.

s axle was fitted to the test vehicle, which was why ictor frame had parallel side members and 3-in.-wide .prings. When the heavy-duty unit is fitted, 5-in.springs are supplied, in which case the frame lembers are swept inwards forward of the rear-spring front hanger brackets, reducing the frame width at this point from 3 ft. 1 in. to 2 ft. 41,in.

The Dyson semi-trailer provided for my road test was considerably oversize by normal British standards. It was a I6-17-ton 40-ft. platform unit built specially to carry steel bars. The main frame members are 7-in.-deep rolled-steel channels and bracing is provided by angle-iron strainers, the complete assembly being welded together. The semi-trailer has a four-spring-and-balance-beam bogie and two-line air-pressure braking, with Girling wedgeoperated two-leading-shoe wheel units.

Because of the overload capacity of the Michelin 9.0020-in. X tyres fitted to the tractor and semi-trailer, Seddon's decided to load the outfit close to the export rating of 32 tons gross, giving a payload of 21 tons 2+ cwt. The load was evenly distributed down the platform and the tractor driving axle and the semi-trailer axles were almost equally laden.

For its initial tests, the outfit was taken to a reasonably quiet level stretch of road, where braking figures were obtained. In view of the comparatively small facing area for a vehicle of this weight, the braking performance was satisfactory, but there seemed to be some fault with the braking circuit which made it difficult to achieve full pressure before making each stop. Nevertheless, the available pressure was sufficient to cause the leading bogie wheels to lock when stopping from 30 m.p.h., the wheels leaving skid marks 43 ft. long—half thc total stopping distance.

Using the semi-trailer-brake hand valve, emergency stops were made with the hand brake from 20 m.p.h. These produced an average Tapley meter reading of 17.5 per cent., which is a fair figure for this weight of articulated outfit.

For the acceleration tests, the low auxiliary section of the gearbox was used and during the standing start runs up to 30 m.p.h., second, third, fourth and top ratios in the main box were employed. Exceptionally good times were recorded, helped by the ability of Mr. Frank Galbraith, of Seddon's, who was driving, to make quick gear changes without double-declutching. Equally remarkable were the direct-drive times recorded between 10 m.p.h. and 30 m.p.h. I noted with astonishment that the engine pulled away happily from speeds as low as 5 m.p.h. in this gear and that at no time during acceleration was there. any roughness of either the engine or the transmission. This top-gear performance indicates the good pulling power of the unit, which, combined with a relatively high governed speed, produces an overall topgear performance far in excess of that normally encountered in British vehicles. While turning round during the braking and acceleration tests, the vehicle was found to possess a degree of manceuvrability which its length would not suggest possible. Study .of the semi-trailer bogie tyres when reversing on full lock showed an appreciable amount of tyre distortion, resulting at times in the road surface being broken up. This distortion is a characteristic of Michelin X tyres and is caused by the soft side walls: under similar conditions a conventional tyre with harder side walls would not deflect to the same degree and scrub would occur, with consequent detriment to tyre life. B18 Using a fuel test tank for maximum accuracy, a consumption test was made along part of Broadway at Chadderton. During this run we had to stop at four sets of traffic lights and as it was necessary to accelerate away from a standstill on each occasion, the fuel figure of 8.7 m.p.g. was even more remarkable. It indicates that on a normal trunk run—even under British conditions—a clear '9 m.p.g. should be obtained with the overdrive gear. The time-load-mileage factor of 6,855 is one of the highest ever recorded by The Commercial Motor and is a clear 2,000 better than is normally obtained with most vehicles of only about half the test weight of the Seddon outfit. Had it been possible to make a run at the maximum speed of nearly 45 m.p.h., a time-load-mileage factor of about 10,000 would probably have been obtained—a figure which even nowadays is beyond the realms of possibility with most vehicles under the most favourable conditions. Buckstones Road, Shaw—the usual Seddon stamping ground—was the scene of the hill-climbing and brake-fade tests, which were made in an ambient temperature of 50° F. This hill has an average severity of 1 in 12 and is 11 miles long. The ascent was made in a total time

minutes. the radiator coolant temperature rising ' F. from its normal value of 145° F. No exhaust was observed at any time.

is driving and kept the auxiliary section of the gear.' the low range, the lowest main ratio employed second, which was engaged for approximately utes. A subsequent climb made during the stopstart test indicated that I would have saved time id had the confidence to change into second high as :.rmediate step in changing up to third low on some less steep sections of the hill.

amiliarity with the technique required with the gearlade it difficult for me to ensure positive split ng. The technique is somewhat different from that ved with a two-speed axle and demands precise and engine-speed control.

Drums Smoke on Fade Test :.heck for fade resistance I then coasted the outfit he hill in neutral, relying on the foot brake to keep :ed down to about 20 m.p.h. This test lasted some 'Lutes and at the bottom a foot-brake stop from 1.h. gave a Tapley meter figure of 25 per cent. All Ims smoked abundantly, as the facings were in no edded-in, the vehicle having covered only 150 miles my test. Maximum braking efficiency was reduced nit half compared with the figures obtained earlier )Id drums. This may seem a severe loss of efficiency e circumstances were abnormal and there was still . safety margin.

ng the descent the engine was kept idling, as is On such occasions, and after making the stop at ttom of the hill the pressure in the front and semibrake circuit dropped to 62 p.s.i., whilst that in the axle circuit was 78 p.s.i., both pressures having from 120 p.s.i. This relatively quick drop in ores' the front and semi-trailer brake circuit was noticed 'eral occasions, which prompts me to think that y the compressor unloader valve was sticking, ; slow pressure build-up.

outfit was shunted without much difficulty to turn it at the bottom of the hill and it was returned to the t section, where the meter registered I in 61. Here ;topped and the tractor multi-pull hand brake would Id the outfit, although despite the hot drums, it )e held by using the semi-trailer hand control. A

restart was then accomplished in bottom gear with :h auxiliary ratio engaged. It was impossible to on this slope in second low.

On the second day of the test an unladen fuel-consumption run was made over the course used the previous day. Traffic conditions were little better, with the result that the average speed was the same, whilst the consumption rate was 11.4 m.p.g.--not a vast improvement on the laden figure. With clearer traffic I would have expected at least 13 m.p.g., particularly in view of the overdrive ratio.

Other than when experiencing difficulty in making split gearbox changes I was well pleased with the handling of the Seddon outfit, and so long as the usual care was taken on sharp corners, it was not difficult to maintain a high speed, even in heavy traffic.

On reasonably level roads it was possible to pull away from a standstill in second high, which suggests that maximum benefit will be derived from the 10-speed gearbox if it is left in high auxiliary ratio for the most part, particularly with a high-torque engine such as the Cummins. Indeed, in reasonably level country, the 557,1480 five-speed overdrive-top gearbox should be sufficient. As regards starting off, both I and the Seddon driver on several occasions inadvertently engaged reverse instead of second —a dangerous mistake which could be avoided by providing a more positive reverse stop in the gearbox.

No Tugging"

The suspension was satisfactory, whether laden or unladen, and there was none of the " tugging " often experienced with articulated vehicles. Although the steering was a little heavy at low speeds, possibly because of the Michelin X tyres. it was perfectly satisfactory once on the move and power steering should not be necessary.

No maintenance was conducted on the outfit, as the tractor follows conventional Seddon practice for forward control heavy-duty chassis, the normal procedures with which have been dealt with in The Commercial Motor. The principal difference in the case of this test outfit concerns the engine, which is made fully accessible by the use of a three-piece, quickly removable plastics engine cowl. As for the engine itself, having had no experience of its maintenance and its unique fuel-induction system. I preferred to let well alone.

The Dyson fifth-wheel coupling proved easy to operate when disconnecting the tractor for the weighbridge check. The outfit was " split " single-handed in 2 minutes 10 seconds, this time including applying the semi-trailer parking brake, lowering the landing gear, disconnecting the two brake hoses, releasing the coupling lock, and driving the tractor away.