ROADTEST LEYLAND DAF FT 95.400

Page 44

Page 46

Page 47

Page 48

Page 50

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Leyland Daf's 95.400 may not be as powerful as other premium tractors on the market, but it can compete equally on performance and fuel economy.

• The halls of the NEC are echoing to the sound of a stampede of high horsepower tractors, with two runaways cracking the 500hp (368kW) barrier being hotly pursued by a large posse boasting more than 450hp (331kW) apiece.

Pity poor Leyland Daf, then, whose big news at Birmingham is a premium tractor with a 'mere' 295kW (401hp) at the driver's disposal. While this output is not to be sniffed at, such is the pace at which the competition is upping the power-play stakes that the Anglo-Dutch concern is in danger of being left behind.

The problem, of course, is that having rejected proprietary engines, the company has to rely on its 11.6-litre block for the bulk of its heavyweight models from 24 tonnes upwards. This is fine lower down the range, but in premium units where rivals can call upon anything from 19 to 17 litres, the Daf block is struggling to produce the power (and more importantly torque) to compete on equal terms.

Until its engineers can come up with a diesel with more cubes — and we understand a bigger six is being worked on — the company is left to claim that the new 400 has just the right amount of power "for a balanced and viable operation". As we found, however, this marketing hype could have some truth in it.

There is more to the new 95 than a bit more urge, however. As well as the old 310/350/380 line-up being replaced by an uprated trio (badged 330/360/400), the re mainder of the truck has been given a series of detail changes intended to keep it up to date, and to reinforce its position relative to the rest of the Leyland Daf tractor range.

This last point has become more significant now that the company is not only• offering the new Roadtrain-based 80 Series, but has also taken the rather bizarre decision to import the updated 2800 tractor, now called the 3200.

As the 95 moves upmarket, then, it is perhaps fitting that for our first experience of the new vehicles, we were able to take the top-of-the-range flagship, the 95.400 in Space Cab form, around our Scottish test route.

Even ignoring the high-horsepower models heading up the ranges of rival manufacturers, the new 400 has no shortage of more direct competition. To succeed it must cope not only with Scandinavians, like the Volvo F12-400 and the Scailia R143-400, but also with a host of British trucks with Cat, Cummins and now Perkins (Eagle Tx 400) propulsion. The similarly cabbed Pegaso Troner must also be worth a look for Continental operators.

• BODYWORK

Even three years on, the 95 Series cab looks as modern as anything else on the road, especially with the high-roof Space Cab. With many competitors adopting the more conservative Mercedes-like approach to styling, could it be that some buyers are still put off by the high-tech appearance? If so, perhaps the sight of the same Cabtec design on the front of a Seddon eight-legger will help ease the problem.

The Space Cab comes complete with an adjustable roof spoiler and side skirts, and the package looks impressively aerodynamic. Wheelbases of 3.25, 3.50 and 3.80m are offered with sleeper cabs, with the longest one being recommended for operation at the 16.5m limit (if a day cab or top sleeper is specified, the 3.5m chassis is also suitable); our truck came with the 3.25m option.

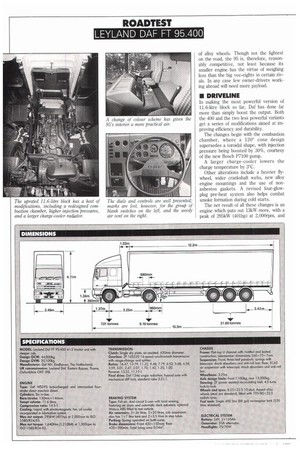

Fully fuelled, the test vehicle tipped the scales at a touch under seven tonnes, partly thanks to 100kg of help from a set of alloy wheels. Though not the lightest on the road, the 95 is, therefore, reasonably competitive, not least because its smaller engine has the virtue of weighing less than the big vee-eights in certain rivals. In any case few owner-drivers working abroad will need more payload.

• DRIVELINE

In making the most powerful version of 11.6-litre block so far, Daf has done far more than simply boost the output. Both the 400 and the two less powerful variants get a series of modifications aimed at improving efficiency and durability.

The changes begin with the combustion chamber, where a 120° cone design supersedes a toroidal shape, with injection pressure being boosted by 30%, courtesy of the new Bosch P7100 pump.

A larger charge-cooler lowers the charge temperature by 3°C.

Other alterations include a heavier flywheel, wider crankshaft webs, new alloy engine mountings and the use of nonasbestos gaskets. A revised four-glowplug pre-heat system also helps combat smoke formation during cold starts.

The net result of all these changes is an engine which puts out 13kW more, with a peak of 295kW (401hp) at 2,000rpm, and 114Nm extra torque, making 1,640Nm (1,2101bft) at 1,300rpm; more important, it holds over 1,600Nm (1.1801bft) between 1,000 and 1,600rpm.

To cope with the increased output, the driveline gets a lOmm larger clutch and a stronger propshaft, and is teamed up with the latest Ecosplit gearbox from ZF, with the 16S-220 variant taking over from the 16S-160.

The new 16-speed range-change and splitter synchro box not only has a much higher torque capacity (enough for the 190.48 TurboStar, incidentally), but also a lighter alloy casing.

• PERFORMANCE

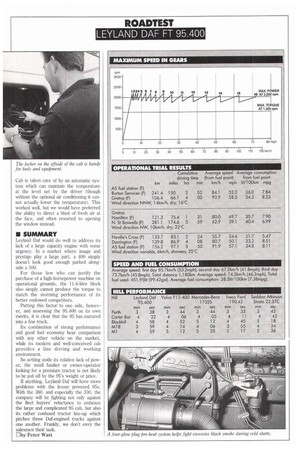

Though the 95,400 was no quicker than the old 380 against the stopwatch, according to our test track figures, its superior torque spread was reflected in a quicker overall speed around our test route and in reduced hill-climb times up the long drags of the M18 and Ml.

At the legal limit the engine is turning at a comfortable 1,650rpm, and most motorway and dual carriageway inclines can be tackled in top with the motor digging in nicely at around 1,300-1,400rpm where it feels hungriest for work.

The picture is only spoilt slightly by the increase in noise levels and driveline vibration as the revs drop through 1.30Orpm.

With 16 speeds to play with, swiftly taken splits in hilly country can keep the engine where its torque output is greatest, and where it is at its most efficient. The SEC curve is well below 200g/ kWh between 1,000 and 1,800rpm, which promises good results at the fuel pumps.

In most conditions the gearchange is a reasonable ally for the driver, with the speed of splits limited only by the speed of hand and foot. Full-lever movements, particularly changes across the gate or through the range change, need to be made more deliberately, but we never had a problem finding gear.

The combined splitter and range-change collar used on the 95 is reasonably driver friendly, and a world away from the infamous ZF double-H arrangement, though we did find the collar a bit difficult to get hold of in a hurry when changing between ranges.

The 95.400 also benefits from a change in the gearing of the latest Ecosplit box, which provides a lower bottom gear ratio of 16.47:1. We didn't have the nerve to verify the claimed 41% (1:2.4) gradeability, but a restart on a very steep section of the A68 was easier than it had any right to be on a greasy road surface.

• ECONOMY

.The improvement in the efficiency of the 95.40, compared with the 380, is illustrated vividly by their fuel figures.

While the 380 returned 40.0 lit/100km (7.06mpg) at an average 73.4km/h (45.6mph), the latest 95 managed an excellent 38.31it/100km (7.38mpg) at a rapid 74.3km/h (46.2mph). Given that the journey times were as quick as anything else we have tested, the performance/economy balance of the new truck is really formidable.

For comparison, Volvo's F12-400, which until now has set the standard for the more powerful tractors we have tested, recorded 39.21it/100km (7.21mpg) at 72.5km/h (45.1mph).

As an indication of the potential of the Leyland Oaf, it gave its best on dual carriageways and motorways and on the run down through Yorkshire on the Al it averaged 3:3.2 lit/100km (8.51mpg), which is enough to bring a warm glow to most transport managers' cheeks.

• HANDLING

The 95.400 comes with Leyland Dafs ECAS air suspension as standard on the drive axle, which, as well as making cou pling and uncoupling a simpler operation, it also blesses the unit with a smooth and level ride.

The driver has more than these air springs between him and the road, however, since he sits on an air seat, and the Space Cab is mounted on four-point air suspension. The result is a truly cossetting ride with a total lack of road shock, although someone stepping from an older generation of steel suspended tractor might find the absence of feedback and the jelly-on-a-plate motion slightly disconcerting at first.

Even having grown accustomed to the cab, its lack of initial roll stiffness and the way it gets buffeted by gusts of wind (often prompting unnecessary steering corrections) can be annoying.

The power steering generally offers good control via a sensibly sized steering wheel, though the slightly spongey feeling around the straight-ahead tends to make small corrections on the motorway difficult to perform accurately.

We have no cause to complain about the service brakes, which impressed us with their light and progressive pedal action on the road, as well as their powerful performance on the test track. An exhaust brake proved useful for restraining the vehicle on long descents, but as with many such devices, the amount of retardation on offer was pretty modest.

• INTERIOR

Part of the revised 95 Series package is an updated interior, with the most obvious change being a revised colour scheme for much of the cab trim.

The large fascia moulding is now an attractive dark grey, which serves as a practical compromise between the pitch black of some rivals and the boudoir grey of earlier 95s; pleasant stripey seat fabric completes the picture.

Taken as a whole, the presentation and quality of the driving environment is now beyond serious criticism. The multiadjustable seating position is sound; the controls and instrumentation are well located, and the visibility from the cab is good in all directions.

Heating and ventilation in the Space Cab is taken care of by an automatic system which can maintain the temperature at the level set by the driver (though without the optional air conditioning it cannot actually lower the temperature). This worked well, but we would have preferred the ability to direct a blast of fresh air at the face, and often resorted to opening the window instead.

III SUMMARY

Leyland Daf would do well to address its lack of a large capacity engine with some urgency. In a market where image and prestige play a large part, a 400 simply doesn't look good enough parked alongside a 500.

For those few who can justify the purchase of a high-horsepower machine on operational grounds, the 1L6-litre block also simply cannot produce the torque to match the storming performance of its better endowed competitors.

Putting this factor to one side, however, and assessing the 95.400 on its own merits, it is clear that the 95 has matured into a fine truck.

Its combination of strong performance and good fuel economy bear comparison with any other vehicle on the market, while its modern and well-conceived cab provides a fine driving and working environment.

So setting aside its relative lack of power, the small haulier or owner-operator looking for a premium tractor is not likely to be put off by the 95's weight or price.

If anything, Leyland Daf will have more problems with the lesser powered 95s. With the 360, and especially the 330, the company will be fighting not only against the fleet buyers' reluctance to embrace the large and complicated 95 cab, but also its rather confused tractor line-up which pitches three Daf-engined trucks against one another. Fratildy, we don't envy the salesmen their task.

Eby Peter Watt