HEAVY METAL

Page 164

Page 165

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

New legislation has forced operators to look more carefully at the cost of their special types trailers and has prompted a move towards dual-mode equipment, an area which is dogged by legal grey areas.

• For years moving a heavy and indivisible load was only a matter of buying a big enough trailer. The special types legislation was enforced haphazardly, and provided you made the correct notifications to the police (and signed the damage disclaimer forms) no one looked too closely at the trailer.

The latest law on special types (STGO) has changed things, and operators which have loads to transport that need vehicles which will be outside the normal construction and use (C&U) regulations are having to look much more closely at specifying the trailer.

A modern STGO trailer is not going to be cheap. For something that basically consists of a steel frame, a floor and some wheels, it would seem a simple matter to design a trailer to carry almost any given load. But it is all too easy to spend upwards of L20,000 on something that is useful or legal for only one type of load.

The authorities appear to regard STGO units and trailers as easy targets, and policemen with measuring tapes have been seen outside yard gates waiting for someone to come out. The most frequent point at issue has been using a trailer designed to carry a load outside C&U for moving smaller items, which could be moved within those regulations — on a shorter or lighter trailer.

At the lighter end of the STGO scale this has led to a demand for dual-plated trailers which can operate legally inside C&U for smaller loads and under STGO for the bigger stuff. Although the market

remains quiet there has been some increase in the number of semi low loader or step frame designs, which remove the cost and complication of hydraulic necks, yet they can be built low enough to allow easy loading of heavy plant.

The market for heavy trailer work, like all other haulage, is substantially down this year. A drop of 25% is widely quoted. This is unfortunate for the makers, but also for the operators which are under pressure not to spend money.

But this comes at a time when heavy trailer fleets need to be urgently updated to cope both with the new legislation and increased levels of policing. And few things are worth less than an obsolete heavy trailer.

In the days when no one looked too closely at axle spacing and weights and when length laws were largely ignored these trailers could be used for years with just a new wood floor every so often. But design has moved on, and the use of high-yield steels in order to maximise trailer payload is growing, particularly for multi-purpose vehicles.

But the move towards dual-mode operation brings its own problems. It means extra complexity, and cost, and as with any compromise is likely to do neither job as well as dedicated equipment. It could mean less payload in both classes of work, and give the police more reasons to stop and check the vehicle.

GREY AREAS

At present there are various grey areas in the legislation, such as the definition of "normally used". This comes in when a trailer is used on a return journey carrying something which could be carried within C&U, but if the trailer is "normally used" for STGO then it can be so used. If however you use a special types trailer regularly to carry smaller items then you will be outside the definition.

That is of course reasonable, but how can "normally" be defined? There is no official answer to that but those in the industry believe that as long as records show something like a 70% use in STGO, that ought to be definable in court. However, as King Trailers stresses in its recently updated guide to STGO rules, this has not yet been legally established, so don't bank on it.

The legislation is still fluid, as the ministry, pressed by the industry, tries to iron out the anomalies without having to go to the complication of bringing in more laws. The result is that at present it is getting more difficult to know precisely what to buy. Operators think they known, but sometimes get caught out. Len Fuller at Andover Trailers quotes a case of one operator which rang up to say it was very pleased with its new trailer but "we couldn't use it, as the police were waiting at the gate". In this case the operator had only one trailer, but the police wouldn't allow its use on loads that did not strictly need an STGO trailer.

In STGO operation, C&U length limits do not apply, provided the trailer is of the low-loader type. But there is confusion at present about how the proposal to limit the lengths of STGO trailers when used under C&U will work. This rule will (from April 1991) put an 18-metre limit on the overall length of an STGO trailer being used for the time being under C&U, and sensibly, will not require it to comply with the latest turning circle rules applicable to normal trailers.

This means that many trailers now in use will not be able to be used under C&U at all, which will mean buying one that can, or completely avoiding any C&U work. These limits could, according to trailer type, restrict deck length to about 5.8m, whereas 6.1-7.3m is common on this class of vehicle at present. It could even lead to operators bringing trailers in to have 600mm (two feet) or so chopped out of the length, rather than buy new.

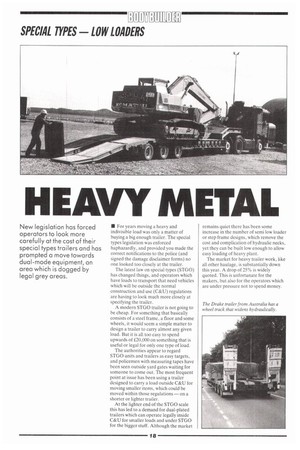

One operator which believes it has the ideal compromise is Desmond I lollingworth of Cumberworth near Iluddersfield which imports the typeapproved Drake trailer from Australia. Its 13.1m tri-axle semi has a wheel track that widens hydraulically from a standard 2.49m for normal C&U road use, to 2.74, 3.05 or 3.35m wide for Cat 1 or 2 loads.

Each side extends, taking the bed ramps, running gear, side marker and tail lights with them. A series of pneumatic locks hold the triple wheel/stub axle sets in position. One area which has received more attention recently is the humble ramp. Design of a ramp may seem simplicity itself, but specifying the right ramp is not easy. For loading over a step frame. for example, it is essential to keep the loading angle small enough for plant not to ground on the way up, and that means something like a 9° slope.

WIDE CHOICE

This can mean several sections to the ramp, adding cost and weight, but the risk of a loading accident tends to increase with steeper ramp angles. With ramps you have a wide choice of one piece or double of varying width, and hydraulic or spring assisted operation. You get what you pay for, and it may cost £2,000 or so for a good one. But the right design is critical for both ease of loading and safety, so it should not be left as an afterthought in the specification process. One dropped load can lose you a lot of business, however good the insurance cover may be.

Users are now specifying air suspension almost entirely, according to major suppliers. The better ride and handling of the rig is one reason, but being able to dump the suspension for easier loading is another and is well worth the money.

Self-steering rear bogies, to combat tyre scrub, are now more common but these are tricky when reversing, a bit like the average supermarket trolley. The only real answer here is for fully powersteered axles, but these add a lot to the cost. Many countries in Europe specify fully steering axles for this kind of work.

The days of blatant overloading of axles and scant regard to the law on special types are over. So be sure you go through weight distribution calculations carefully with your supplier.

E. by John Parsons