DRUMMING UP SALES

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Since 1981 Lucas Girling's export of truck brakes has rocketed from 3% to 35% of total production — and is predicted to top 60% within two years. CM has been to see the technology behind the success story

• If there is a single European town or city that may be considered as the heartland of truck foundation brake technology it is not, as might be supposed, Stuttgart, Lyons, Turin or Gothenburg, but Cwmbran in South Wales.

That is where Lucas Girling's Heavy Duty Brake System Division has its main manufacturing and research and development base.

Five years ago most brake engineers from truck manufacturers outside the UK almost certainly would not have heard of Cwmbran, and probably knew little or nothing about Lucas Girling. After all, only 3% of the company's annual production of truck brakes was exported. Today that figure stands at about 35% and Stan Ankrett, Lucas Girling's marketing manager for CV brakes, is confident that within another two years it will have grown to at least 60%.

While the majority (currently about 65%) of the Western European truck brake market is taken by the truck manufacturers themselves with in-house designed and built products, specialist brake manufacturers have recently begun to make significant inroads — and Lucas Girling is leading the way.

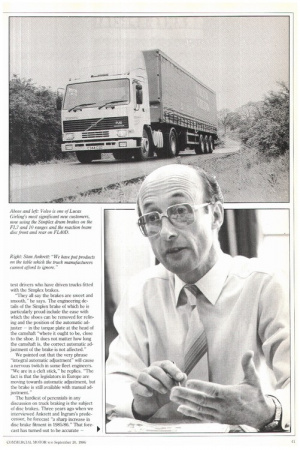

Among its relatively new, mainland European customers are Volvo, Daf, MAN and Daimler-Benz. Further afield, Lucas Girling truck brake customers include Ford in the USA and Brazil, and Hino, Mitsubishi and Nissan in Japan. Ankrett reckons that his company now takes about 13% of the European truck brake market, the total value of which he puts at "something like £120 million." Be says that yet-to-be-announced, but firm new contracts will take that share to 22% by 1988.

Why are truck manufacturers which have always designed and built their own foundation brakes turning increasingly to specialist manufacturers like Lucas Girling, or its major competitors Rockwell, Bendix and Perrot? Ankrett cites a prime reason as "the investment that has to be put into engineering and manufacturing a modern truck brake to be commercially and technically competitive. We put products on the table which they cannot afford to ignore."

One product which evidently made a strong impression on Volvo engineers during the FL7 and 10 development programme is Lucas Girling's latest cam brake developed from the familiar FCSS (fixed cam sliding shoe) brake which it calls the Simplex Cam. Volvo now uses this brake in place of its own S-cam on all FL7 and 10 trucks and calls it the Z-cam. Despite having tried long and hard to improve the performance of its own S-cam, Volvo finally reached the conclusion that it could not be brought up to the standard required.

Brian Ingram, Lucas Girling's chief engineer for truck brake systems, has some firm views on S-cam brakes in general: One of the key reasons for the very existence of our Simplex brake is the maintenance problems associated with Scams. Yes there are good S-cams and. not so good ones, but they all suffer in one way.

"Once you pivot the shoe you cannot maintain constant drum-to-lining contact, and when you change the camshaft you change the contact point. With sliding shoes, as the brake is applied the shoes are in a position to shuffle themselves to give the 'best fit', and there is some flexibility in the shoes to accommodate the deflections that occur." He concedes that one disadvantage of the sliding shoe design is that its lining wear pattern cannot be defined so precisely. "One good thing about a pivoted shoe (S-cam) is that you know what the wear pattern is going to be." Nevertheless, Ingram says that by "getting the geometry right" Lucas Girling has minimised this disadvantage on its Simplex brake and that anyway it is a small price to pay for its other inherent advantages. "By giving the shoes this freedom we significantly reduce drum damage, which we believe is a major issue on S-cam brakes in certain operating conditions. On low power-to-weight ratio vehicles perhaps you will not see it, but above a certain threshold the level of drum damage significantly increases."

Ingram is pleased, although not surprised, by the comments of independent

test drivers who have driven trucks fitted with the Simplex brakes.

"They all say the brakes are sweet and smooth," he says. The engineering details of the Simplex brake of which he is particularly proud include the ease with which the shoes can be removed for relining and the position of the automatic adjuster — in the torque plate at the head of the camshaft "where it ought to be, close to the shoe. It does not matter how long the camshaft is, the correct automatic adjustment of the brake is not affected."

We pointed out that the very phrase "integral automatic adjustment" will cause a nervous twitch in some fleet engineers. "We are in a cleft stick," he replies. "The fact is that the legislators in Europe are moving towards automatic adjustment, but the brake is still available with manual adjustment."

The hardiest of perennials in any discussion on truck braking is the subject of disc brakes. Three years ago when we interviewed Ankrett and Ingram's predecessor, he forecast "a sharp increase in disc brake fitment in 1985/86." That forecast has turned out to be accurate — discs, most notably Lucas Girling's reaction beam disc brake, have at last begun to make an impact in Europe on trucks of about 7.5 tonnes GVW. Is that impact likely to extend to heavier vehicles within the next three years?

Ingram thinks not. "We do not see heavy truck drum brakes being superseded in the forseeable future. We have developments that we cannot yet talk about which will ensure the drum brake will continue. We believe there is still a fair amount of scope in drum brake design. We see our disc brake as a means of extending our business base rather than changing it."

The reaction beam disc brake has already extended Lucas Girling's business significantly. It is, for example, used on Volvo FL4s, the Mercedes-Benz LN1 range, Hino's Ranger models and Ford F4000s in Brazil as well as Ford Cargos in Europe (the one case where it has displaced a Lucas Girling drum brake).

Why has this particular disc brake gained wide acceptance where earlier designs, from Lucas Girling and others, have failed?

Ankrett says it is important to differentiate between vehicles up to about 10 tonnes GVW and those above that weight, and to consider the type of drum brakes which have been used on the lighter trucks. "They were typically a twoleading-shoe front brake and duo-servo, or similarly complicated rear brake, which led to a variation in brake performance from front to rear. This contrasts with S cam braked heavier vehicles where at least the brake factor was the same on front and rear axles." Ingram adds that, in the four to 11-tonne GVW weight category, compared with existing drum brakes "almost without exception our disc offers better lining life, with improved stability and performance. In the past disc brake manufacturers, including ourselves. have gone for the most difficult (heavier) vehicles. Any driver who gets out of a drum braked 7.5-tanner into a disc braked one will almost immediately be aware of generally better braking performance. With the better S-cams the step to discs is not quite so obvious."

According to Ingram the main reason for truck disc brake activity having been held back until recently has been the problem of rapid pad wear. He says that Lucas Girling has solved that problem with its reaction beam design, primarily through using a relatively thin bridge section which allows an increase in disc diameter and thus an increase in swept frictional area.

"In the old designs of disc brake the structure imposed uneven pressure, and thus rapid wear on the disc." When Ford's Concept Cargo — one of the first trucks to be fitted with Lucas Girling reaction beam disc brakes — was unveiled in 1982, the brake manufacturer made predictions on pad life which few people believed — at least twice the life of the drum brake linings then being used on the Cargo. Lucas Girling says that this is no longer a matter of speculation, but one of fact.

Ingrain and Ankrett are ready to admit, however, that some of their comments of a few years ago are no longer valid. On wheel sizes, for example, three years ago Lucas Girling, like many European truck manufacturers, expected to see 22.5in wheels superseded by 24.5in components.

In fact the 24.5in wheel has not caught on, despite the opportunity it offers brake manufacturers to increase disc diameter, because it has not delivered the promised fuel economy improvement over 22.5in wheel and tyres and, as Ingram puts it, "there is a lot of vested interest in keeping the 22.5in wheel."

Certainly Lucas Girling's disc brake engineers have learned to live with this size. In 1983 the company said that the largest diameter disc it could squeeze into a 22.5in wheel was 380mm. Now Ingram says he can get a 444mm disc into that wheel size. The wheel and tyre development which is of most interest to the Lucas Girling engineers at the moment is one in the opposite direction, towards smaller diameter wheels on 16 tanners. "We are struggling right now to predict how many 16 tanners will soon be on 19.5in wheels," says Ankrett.

He believes that the tyre development necessary to take the maximum GVW for that size from the current 15.6 tonnes to the important 16.26 tonne threshold is "only just around the corner," and he says that Lucas Girling has brakes ready for it.

by Tim Btakemore