A Vehicle Built for HARD WORK with economy

Page 14

Page 15

Page 16

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By L. J. COTTON, M.1.R.T.E.

THERE is no great need for frequent gear changing on the

Bedford Scammell outfit, because with the high torque of the engine in the medium-speed range. the power unit will continue pulling hard at low road speeds.

At first I drove the Bedford prime mover as a machine with a low power-to-weight ratio should be driven, changing down as soon as the engine revolutions began to fall. Subsequently, I "hung on" in the higher ratios for longer periods and found that the engine had a great reserve of power, which could be used to give an economical consumption without prejudice to a good average road speed.

The present Bedford 28 h.p. petrol engine has not been altered to any great extent from the model used by the Forces in all parts of the world. Although the basis of the design is unchanged, and its capacity remains as before, the output has been raised to 70 b.h.p. with all accessories connected. • The gearbox is built as a unit with the clutch and engine, and the complete assembly is mounted in the frame at three points, all on rubber insulation. The standard four-speed gearbox has a... cast-iron casing, detachable top and a power take-off face at the side. A single-piece pro. s8 peller shaft, with mechanical universal joints, transmits the drive to the spiral-bevel assembly of the axle.

A built-up assembly, the Tear-axle casing comprises large-diameter tubes pressed into a malleable-castiron differential carrier. Brake anchor plates and spring pads are welded on the outer ends of the tubes. Axle driving torque is absorbed in the susPension.

As a result of extensive research in frame construction, the cross-members are cold-squeeze riveted to the beams. In the Vauxhall experiments, hot riveting and bolting have both shown weaknesses, whereas with the cold-riveting method, the frame has fractured before movement has been shown in the riveting.

A simple braking system is employed in the tractor. The shoes at all four wheels are connected hydraulically to the pedal and 'a separate vacuum system operates the trailer brakes, The vacuum arrangement, a Clayton-Dewandre self-contained unit, operates through a mechanical linkage in the Scammell coupling to cables which take effect on the Girling two-leading-shoe Units on the trailer. axle.

A separate vacuum pipe line is fitted to the tractor forconnection to the trailer, should the trailed unit be equipped with a servo braking system. The tractor brake shoes are linked to give a servo action, the

loading being automatically equalized by hydraulic pressure.

I collected the tractor from the Luton factory and connected it up to the loaded semi-trailer in another section of the works. The prime mover and trailed unit were coupled in a few seconds, and the Combined unit was then driven to the weighbridge. Here it was found that the alleged 8-ton payload erred on the generous side—a good point, as far as testing was concerned.

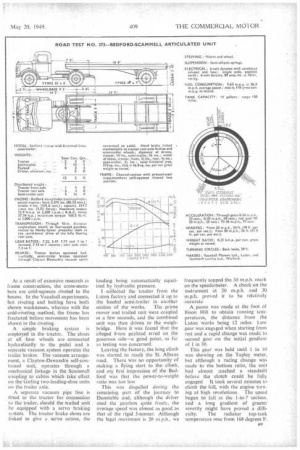

Leaving the factory, the long climb was started to reach the St. Albans road. There was no opportunity of making a flying start to the climb, and my first impression of the Bedford was that the power-to-weight ratio was too low This was dispelled during the remaining part of the journey to Dunstable and, although the driver used the gearbox quite freely, the average speed was almost as good as that of the rigid 5-tonner. Although the legal maximum is 20 m p.h., we frequently topped the 30 m.p.h. mark on the speedometer. A check on the instrument at 20 m.p.h. and 30 m.p.h. proved it to be relatively accurate.

A. pause was made at the foot of Bison Hill to obtain running temperatures, the distance from the Luton works being 12 miles. Low gear was engaged when starting from rest and a rapid change was made to second gear on the initial gradient of I in 30.

This gear was held until I in l0 was showing on the Tapley meter, but although a racing change was made to the bottom ratio, the unit had almoSt reached a standstill before the clutch could be fully engaged It took several minutes to climb the hill, with the engine turning at high revolutions. The speed began to fall at the l-in-7 section, and a long gradient of greater severity might have proved a difficulty. The radiator top-tank temperature rose from 1[68 degrees F.

to 179 degrees F. during the climb Ambient was 53 degrees F.

The journey was continued past Whipsnade Zoo to a road fork where the turning circle could be checked. A complete forward turn was made, with the semi-trailer 'attached, in a circle Of 39-ft. diameter. Of course, a closer turn c'an be made by shunting, .and, as a point of interest, and with a fair amount of exertion on the steering wheel, I did turn the complete unit in a road 35 ft. wide.

Initial acceleration tests, made on a stretch between Dunstable and St. Albans, showed exceptionally lively acceleration in one direction, but on the return run the time taken was totally out of proportion I then drove to Silsoe, on the A.6 road, and found a reasonably level stretch, where acceleration time in either direction did not vary by more than 5 secs.

Smooth Acceleration There was nothing outstanding in the results, but the top-gear performance showed that the engine power was reasonabfy proportioned to the load From 0-20 m.p.h., through the gears, took. 23 sees., and 25 secs. were required in accelerating from' 10-20 m.p.h .' in direct drive. . Tomgear performance at low speeds was notably smooth, and there was no hesitation from the engine when the throttle was snapped open at 8 m.p.h.

Braking trials were made immediately afterwards, and as the results show, the efficiency ' was high, especially for an `articulated outfit. When making these tests, there was some protest from the tractor-trailer • coupling, the shocks transmitted to the cab being sufficient to ,deter any driver from using the brakes fiercely as a standard procedure.

. Shock Tactics There was a continuous snatch and push between the prime mover and semi-trailer as the vehicle was brought rapidly to rest. The stopping distanee from 20 m.p.h. was 24 ft., and from 30 m.p.h., 55 ft.

It was during the top-gear timed tests that I discovered the good " slogging " power of the Bedford engine at low speeds. This was used to advantage during the consumption trials, and although the course from Offley, through Letchworth, and branching off to Hexton, was neither level nor straight, most of the distance was covered in top gear. Instead of changing from direct drive to a lower ratio at 20 m.p.h., I delayed changing down until between 12 and 15 m.p.h., according to the severity of the gradient.

The total distance covered on this test was •15 miles, and the maximum pi 0

speed on level and downhill stretches was restricted to 33 m.p.h. The highly economical result of 9.3 m.p.g., at an average speed of 26.5 m.p.h., is sufficient to show. why there are still so many petrol-engined .articulated vehicles engaged on long-distance haulage.

On a check run •in the opposite direction, almost precisely the same time and consumption rate were obtained, proving that this was no

freak performance. I have since found that many operators are obtaining the same, Of a better, performance from Bedford vehicles operating with a similar load

Returning to the works, a detour was made so that the brakes could be tested on the long decline leading into Luton. For this test, the brakes were applied to restrict the speed to 25 m.p.h., a serious test.

Brake-pedal movement increased with the distance, and by the time the foot of the hilt was reached, there was a trace of fade in efficiency Heavy-vehicle drivers would normally engage a low gear when descending a hill of this length or severity. It did not take long for the drums to contract and for the brakes to be restored to their original high efficiency.