Leyland Buffalo tractive unit at 32 tons gm

Page 59

Page 60

Page 61

Page 64

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

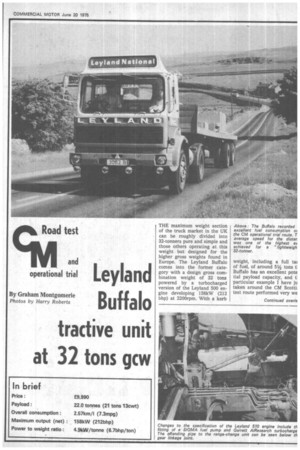

THE maximum weight section of the truck market in the UK can be roughly divided into 32-tonners pure and simple and those others operating at this weight but designed for the higher gross weights found in Europe. The Leyland Buffalo comes into the former category with a design gross combination weight of 32 tons powered by a turbocharged version of the Leyland 500 engine developing 158kW (212 bhp) at 2200rpm. With a kerb

Above : The Buffalo recorded excellent fuel consumption ot the CM operational trial route. T average speed for the distar was one of the highest ev achieved for a lightweigh 32-tonner.

weight, including a full tai of fuel, of around 51/2 tons t. Buffalo has an excellent pote tial payload capacity, and t: particular example I have ju taken around the CM Scott: test route performed very we

Continued overle

7ntinued from page 57

.turning an overall fuel conamption of 2.58km/1 (7.3 tpg).

The turbocharged version of le 500 series — designated le 510 — has been subject ) a few modifications since its nnouncement. The main hange was to the fuel-injec;on equipment with a Sigma ump and a Garrett AlReearch turbocharger now being tandard equipment. The gear ox was from the Fuller Roadanger series, in this case the ine-speed RTO 609, coupled -ii-ough a Lipe Rollway twin late clutch.

Performance

With a power-to-weight ratio f 4.9kW/tonne (6.7bhp/ton) he Buffalo had an adequate erfortnance capacity for the /eight without being startling. Vhen compared with trucks f a similar specification, the luffalo just had the edge in erms of acceleration. The atios in the Fuller box were • ery well matched to the haracteristics of the 510 enme. This meant that, for ince, the right ratio for the onditions was nearly always Taking the Carter Bar hill .s an example the Buffalo went tearly the whole way up in Sth gear at 1900rpm with ine brief drop into fourth near he summit. Usually on this Liii a truck will accelerate until he engine comes onto the ;overnor, but when the next ;ear is selected this proves too iigh with the final result that he climb is tackled with the :ngine on the governor in the ower gear. This did not hap)en with the Buffalo, which ait up one of the fastest times n its category on this partiular section of the CM operaional trial.

With the torque characterisics of the Leyland engine I ound it best to change up at 'round 2200rpm and down at tround 1500rpm. On the notorway sections the Buffalo vould cruise happily near the ;0 mark although the in-cab wise level at this speed was Tery intrusive. The engine was tery flexible and if necessary would pull strongly from tround 1100rpm to save an :xtra gearchange.

On the test hills at MIRA he Buffalo restarted from rest )n the 1 in 6 gradient without )roblems, with the parking )rake coping with the fully aden outfit facing up or down his slope. One minor difficulty mcountered on this part of the .est was the need to be fairly vapid when releasing the park brake. As the vehicle has a combined park/secondary control, releasing the park brake necessitated going through the secondary system position, which had the usual delay in releasing. This meant that care was needed in a restart to ensure that the brakes were fully off before full power was fed through the transmission.

Flexible

Although I described the 510 engine as a very flexible unit, even it had to admit defeat on one steep gradient shortly before the Rochester fuel stop when the Fuller gearbox stuck in high range owing to an air leak in the pipe to the control switch. This had happened because a securing clip had come adrift allowing the plastic pipe to touch the exhaust manifold. However good a truck the Buffalo is, there was no way it could restart on a 1 in 10 in fifth gear.

When it came to adding up the fuel used it quickly became obvious that the Buffalo was going to become one of the best trucks CM has ever tested in this respect. Joining the elite "over seven mpg" club, the Leyland returned an overall figure of no less than 2.57km/1 (7.3mpg) for the round trip.

The individual stage consumptions were consistent as a glance at the full results panel will show. The figures fall into the usual pattern with the best result occurring on the " 40mph " section of Al and the severe A68 stage with the Ridsdale and Riding Mill gradients knocking the fuel consumption down to 2.08km/1 (5.87mpg).

Any truck which can average over 7mpg along the CM route can be regarded as a frugal vehicle, and to exceed this figure as comfortably as the Buffalo did was very creditable. This was achieved in conjunction with an average speed of just over 40mph so the Buffalo was not exactly hanging about to reach this fuel consumption.

In the cab

The cab is the same as that fitted to the six-wheeler Bison tested by CM earlier this year so obviously most of the merits and demerits apply to both vehicles. One of my complaints concerning the Bison referred to the lack of a rev-counter, an omission which was rectified in the Buffalo.

The all-round visibility was good and the low cab line meant that the forward visibility was to within 2.24m (7ft 4in) of the bumper bar.

One severe criticism I had of the Buffalo concerned the seat material. If a truck has a list price of around £10,000 it surely cannot increase the cost by very much to fit cloth covered seats. In a long-distance type of truck non-breathing plastic material is just not on. This factor was brought home very sharply during the extremely hot weather encountered on the Leyland test.

Leyland used to have one of the most effective quickrelease window-winding mech,anisms ever used in a commercial vehicle, but regrettably these have been deleted. The sliding type now fitted was difficult to operate one-handed when driving, as it jammed if it was not pulled up square on to the frame not all that easy when on the move.

In general I liked the basic driving position of the Buffalo as far as the control layout went, but it is a pity that the engine cowl takes up so much space. Leyland claims that one of the major advantages of the low Egromatic cab is the easy entry and exit-but the Buffalo is not a local delivery vehicle so how many times does the driver get in and out on a long haul?

Braking

The stopping performance for the fully laden combination was about average with no untoward problems save a slight tendency to pull to the left under really heavy braking. From 64km/h (40mph) the stopping distance was 34.4m (112ft 10in) for an average deceleration of 0.47g.

On the road section of the test I had complete confidence in the brakes, which performed consistently and well. Even after the long descent of Carfrae Bank in Scotland the brakes showed little sign of fade although the smell of hot linings was noticeable. No exhaust brake was fitted to the Buffalo, which I felt was a serious omission. Although most exhaust brakes will not slow a vehicle down by very much they at least can hold the speed steadily when going downhill. Such a device was severely missed on the Buffalo.

The ride and handling of the Buffalo were rather disappointing especially when compared with the good performances put up in the other categories. Surprisingly the ride of the Buffalo was similar to that of of the wise men of the East (of Scotland), believing them to be jealous of the fact that (as the paper says) Glasgow and its hinterland have had more capital invested in public transport than the rest of Scotland put together.

On the other hand, Glaswegians and expatriates from south of the border will no doubt applaud The Scotsman for asking when Landon weighting allowances ' are likely to apply in Glasgow, and the suggestion that civil servants should resist transfer until the weighting is applicable there.

"