Testing to breaking point

Page 93

Page 94

Page 95

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

by R. D. Cater, AMInstBE

Do makers really do enough to ensure that their new models will prove reliable? They certainly should, because guarantee claims cost a lot of money and often promote bad feeling. New models failing through breakdown to complete one day's work after another, individual vehicles whose records show strings of complaints and numerous modifications—these things provoke laments from operators up and down the country, often concealing deep-seated resentment and a feeling that manufacturers do not do sufficient 'homework''.

Increasing complexity in vehicle design and the need to keep selling prices as low as possible combine to make the production of trouble-free vehicles constantly more difficult. Adequate testing and proving become more important as the products of the motor manufacturers become more complicated, and sophisticated techniques are continually being introduced in order to combat the seemingly ever-present teething troubles.

I have had my share of new vehicle problems and on occasion been ready just to blame the manufacturer. So I decided to see for myself just how one of the country's biggest lorry and bus builders, Leyland Motors, set about planning, designing and proving a new model.

. A long discussion with British Leyland truck and bus division design and development engineer (vehicles), Mr. Roy Aston, demonstrated that little is left to chance. Gone are the days of rule-of-thumb engineering and the quick drive around the block with the latest brainchild, to see if it works.

Nowadays planning starts after a require

ment is received from the market research department giving a rough guide to designers as to next-model requirements. Incidentally at any one time three new models at different stages are on the stocks at Leyland. The reason for this is that design testing and proving exercises are by their nature expensive, requiring quite extensive facilities. Obviously these facilities cost money, and they represent an addition to the cost of every vehicle sold. Therefore only one set of facilities is utilized and the programme staggered so that no two new models require the same test facilities at the same time.

Currently an increase of 100 per cent, from four to eight vehicles, in the number of units from one model range for each test programme is being introduced, so it will be seen that if three new models are being developed, some 24 vehicles in all will probably make up the test fleet. In addition a number of current Leyland vehicles as well as others built by competitors are used for comparative testing.

Once the market requirement has been made known, the design and development department produces a complete specification including calculated figures both for operating and economic performance. Mr Aston made it clear that without this yardstick to work against, even the most sophisticated development programme could not hope to succeed.

Computerized calculation of stress-loadings and the necessary design calculations to cope with them have vastly reduced actual design time. For instance, a designer can now run off a whole batch of suggested dimensions of a unit to be used for a specific job in far less time than it used to take him to calculate the stresses for which he must cater. Once again this results in design overheads being kept down, but, and far more important, it also enables the correct materials and dimensions to be specified very early in the design stage with the knowledge that components so constructed will be as near right as' man has yet been able to make them.

"If this is the case", one might ask, "why the need for testing and proving?" The answer is that many problems which arise in the best conceived projects can only be highlighted through physical testing—witness the Concorde and the American moon flights—and more information must be compiled on how components will perform in service so that all servicing instructions are ready when the vehicle enters operational service.

Any component part that does not break at some time during the test programme is viewed with suspicion and placed on a list to undergo cost and weight reduction evaluation.

Crack testing of parts severely stressed during the pave mileage is carried out. If such items as springs and shock absorbers for instance—being stressed far in excess of what can be expected in actual service—are 'found to be cracked during the inspection, this does not mean that modification may necessarily be required. Replacement might well be expected to be the case by the time the vehicle had completed what would be an equivalent mileage on the road: some pave test tracks are said to accelerate conditions to such a degree that 1,000 miles would represent 100,000 road miles and very much more than that in the case of suspension components.

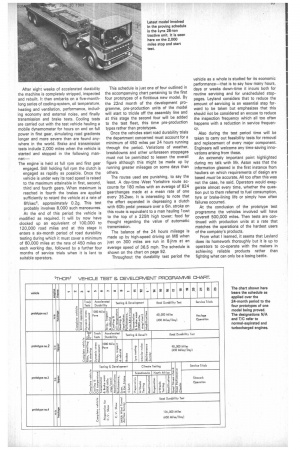

Approximately three months after the prototypes have been laid down they become available to their designers for what is known as an initial appraisal, rather like the road tests carried out by Commercial Motor. From this test the development team assesses the desirability of pressing on with the vehicle without alteration; in other words any really glaring mistakes will show up and be accounted for at this stage before accelerated and endurance testing begins. Two weeks are allowed in the 24-month schedule for the

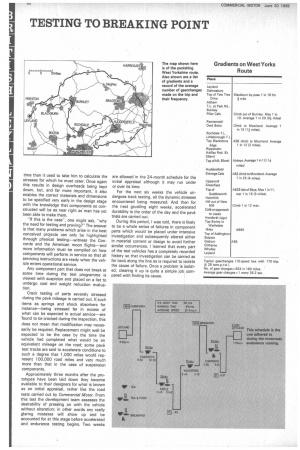

or over its time. U pperm ill initial appraisal although it may run under Greenfield For the next six weeks the vehicle unSaddleworth dergoes track testing, all the dynamic stresses Holmfirth

Hill out of New

encountered being measured. And then for Mill the next gruelling eight weeks, accelerated Cafe on approach durability is the order of the day and the pave to Leeds trials are carried out. Horsforth (sign)

Top Burley in

During this period, I was told, there is likely Wart edale to be a whole series of failures in component Ilkley parts which would be placed under intensive Top of Addinghan investigation and subsequently altered either Skipton

Gisburn

in material content or design to avoid further Clitheroe similar occurrences. I learned that every part Wha Hey of the test vehicles has a completely recorded Leyland

history so that investigation can be carried as far back along the line as is required to isolate the cause of failure. Once a problem is isolated, clearing it up is quite a simple job compared with finding its cause.

After eight weeks of accelerated durability the machine is completely stripped, inspected and rebuilt. It then embarks on a five-monthlong series of cooling-system, oil temperature. heating and ventilation, performance, including economy and external noise, and finally transmission and brake tests. Cooling tests are carried out with the test vehicle hauling a mobile dynamometer for hours on end on full power in first gear, simulating road gradients longer and more severe than are found anywhere in the world. Brake and transmission tests include 2,000 miles when the vehicle is started and stopped in the following manner:—

The engine is held at full rpm and first gear engaged. Still holding full rpm the clutch is engaged as rapidly as possible. Once the vehicle is under way its road speed is raised to the maximum attainable in first, second, third and fourth gears. When maximum is reached in fourth the brakes are applied sufficiently to retard the vehicle at a rate of

6ft/sec2, approximately 0.2g. This test

probably involves 8,000 such manoeuvres.

At the end of this period the vehicle is modified as required. It will by now have clocked up an equivalent of 100,000 to 120,000 road miles and at this stage it enters a six-month period of road durability testing during which it must cover a minimum of 60,000 miles at the rate of 450 miles on each working day, followed by a further four months of service trials when it is lent to suitable operators. This schedule is just one of four outlined in the accompanying chart pertaining to the first four prototypes of a fictitious new model. By the 22nd month of the development programme, pre-production units of the model will start to trickle off the assembly line and at this stage the second four will be added to the test fleet, this time pre-production types rather than prototypes.

Once the vehicles start road durability trials the department concerned must account for a minimum of 450 miles per 24 hours running through the period. Variations of weather, breakdowns and other unforeseen stoppages must not be permitted to lessen the overall figure although this might be made up by running greater mileages on some days than others.

The routes used are punishing, to say the least. A day-time West Yorkshire route accounts for 180 miles with an average of 824 gearchanges made at a mean rate of one every 35.2sec. It is interesting to note that the effort expended in depressing a clutch with 60Ib pedal pressure over a 6in. stroke on this route is equivalent to a man hauling lcwt to the top of a 225ft high tower: food for thought regarding the value of automatic transmission.

The balance of the 24 hours mileage is made up by high-speed driving on M6 when just on 300 miles are run in 8!.hrs at an average speed of 36.5 mph. The schedule is shown on the chart on page 92.

Throughout the durability test period the

vehicle as a whole is studied for its economic performance—that is to say how many hours, days or weeks down-time it incurs both for routine servicing and for unscheduled stoppages. Leyland considers that to reduce the amount of servicing is an essential step forward to be taken but emphasizes that this should not be considered an excuse to reduce the inspection frequency which all too often happens with a reduction in service frequency.

Also during the test period time will be taken to carry out feasibility tests for removal and replacement of every major component. Engineers will welcome any time-saving innovations arising from these.

An extremely important point highlighted during my talk with Mr. Aston was that the information gleaned in the first instance from hauliers on which requirements of design are based must be accurate. All too often this was not the case, he said. Operators would exaggerate almost every time, whether the question put to them referred to fuel consumption, tyre or brake-lining life or simply how often failures occurred.

At the conclusion of the prototype test programme the vehicles involved will have covered 500,000 miles. Then tests are continued with production units at a rate that matches the operations of the hardest users of the company's products.

From what I learned, it seems that Leyland does its homework thoroughly but it is up to operators to co-operate with the makers in achieving reliable products rather than fighting what can only be a losing battle.