AEC Mercury 16 ton-gross four-wheeler

Page 210

Page 211

Page 212

Page 215

Page 216

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

COMPETITION among manufacturers in the maximum-gross four-wheeler field has increased in recent years particularly as a result of the introduction of plating and also because of the probable difficulties in operating over-16-ton vehicles with implementation of the Transport Act. Now every UK maker offers a model in this category. Nine come from five companies in the British Leyland Motor Corporation, the AEC contender being the well-established Mercury which has just been put through a full CM road test and operational trial.

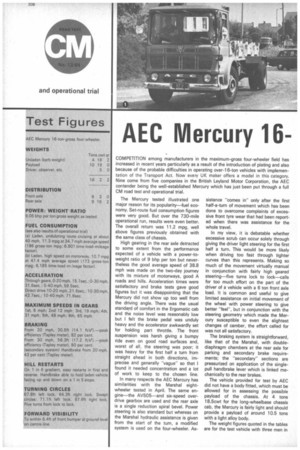

The Mercury tested illustrated one major reason for its popularity—fuel economy. Set-route fuel consumption figures were very good. But over the 730-mile operational run, results were even better. The overall return was 11.2 mpg, well above figures previously obtained with the same class of chassis.

High gearing in the rear axle detracted to some extent from the performance expected of a vehicle with a power-toweight ratio of 9 bhp per ton but nevertheless the good average speed of 38.8 mph was made on the two-day journey with its mixture of motorways, good A roads and hills. Acceleration times were satisfactory and brake tests gave good figures but it was disappointing that the Mercury did not show up too well from the driving angle. There was the usual standard of comfort in the Ergomatic cab and the noise level was reasonably low but I felt the brake pedal was unduly heavy and the accelerator awkwardly set for holding part throttle. The front suspension was harsh giving a bumpy ride even on good road surfaces and, worst of all, the steering was poor; it was heavy for the first half a turn from straight ahead in both directions, imprecise and generally "vague" so that I found it needed concentration and a lot of work to keep to the chosen line.

In many respects the AEC Mercury has similarities with the Marshal eightwheeler tested in April. The same engine—the AV505—and six-speed overdrive gearbox are used and the rear axle is a single reduction spiral bevel. Power steering is also standard but whereas on the Marshal hydraulic assistance is given from the start of the turn, a modified system is used on the four-wheeler. As

sistance "comes in" only after the first half-a-turn of movement which has been done to overcome complaints of excessive front tyre wear that had been reported when there was assistance for the whole travel.

In my view, it is debatable whether excessive scrub can occur solely through giving the driver light steering for the first half a turn. This would be more likely when driving too fast through tighter curves than this represents. Making so much of the movement virtually manual in conjunction with fairly high geared steering—five turns lock to lock—calls for too much effort on the part of the driver of a vehicle with a 6 ton front axle load. It is common and useful to give limited assistance on initial movement of the wheel with power steering to give better "feel", but in conjunction with the steering geometry which made the Mercury susceptible to even the slightest changes of camber, the effort called for was not all satisfactory.

The braking system is straightforward, like that of the Marshal, with doublediaphragm chambers at the rear axle for parking and secondary brake requirements; the "secondary" sections are pressurized on application of the singlepull handbrake lever which is linked mechanically to the rear brakes.

The vehicle provided for test by AEC did not have a body fitted, which must be allowed for in assessing the possible payload of the chassis. At 4 tons 18.5cwt for the long-wheelbase chassis cab, the Mercury is fairly light and should provide a payload of around 10.5 tons with a light alloy body.

The weight figures quoted in the tables are for the test vehicle with three men in the cab, in which condition braking, acceleration, set-route fuel consumptions and part of the operational trial were completed. For 600 miles of the long run, the weight was 1.5cwt less but this is unlikely to have had any significant effect on the figures.

Set-route consumptions were carried out on A6 and M1 south of Luton but a break was made in the operational trial for brake and acceleration tests at MIRA. In spite of high peak efficiencies of over 80 per cent there was very little wheel locking on the brake tests. Only the rears locked for about 3ft 'on 30 mph tests. On the handbrake checks, which gave 43 per cent, there was more wheel locking particularly from the offside with heavy marks for over 15ft. The difference in overall deceleration rate as calculated from stopping distances from 20 and 30 mph indicates that there was some delay in build-up to the maximum efficiency but there was no feeling of delay in the system and, on general driving, there was good response from the pedal although application needed a rather heavy pressure.

While at MIRA hill checks were carried out and it was almost possible to get the Mercury restarted on the 1 in 5 gradient. The handbrake held the vehicle when facing up and facing down the slope with the lever release and therefore without air assistance. Easy restarts were made in reverse and first up the 1 in 6 gradient at MIRA.

In general, the mechanical specification and rear axle ratio of the Mercury tested were perfectly satisfactory for the tests carried out on the vehicle but with an axle ratio of 5.87 to 1 spacings between the maximum speeds in the gears were wider than was the case with the Marshal tested. This would be no detriment if the AV505 engine had not been rather slow to die down. When making upward gear changes, patience was essential to ensure "clean— engagement—an unusually long wait was necessary for the revs to drop from the maximum (in the lower gears) to a suitable level for the higher ratio.

There was no problem on the flat or when running downhill but there was when climbing and coming to an easier part of the gradient. Frequently, on the operational trial and when on hills such as Shap, easing of the slope made a higher ratio possible but not after waiting to allow the revs to die. "Snatch" changes were tried—and completed—but only with a lot of complaint from the gearbox; so much so that there was worry about possible damage. Consequently, the practice adopted for most of the hills on the test was to stay in the lower gear until a proper change could be made.

Similar points about slow engine diedown and difficulty of making "snatch" changes were made in the Marshal report but as this had a lower axle ratio (7.14 to 1) maximum gear speeds were closer and the situation was improved. I feel that there would have been a considerable improvement if the AEC 10-speed splitter gearbox had been fitted to the test chassis and a much better hill-climbing performance would result with this specification.

While on the subject of transmission, there was a good deal of racking in the drive line, probably due to its length and the existence of two centre bearings. This was most noticeable as the engine went through a vibration period which corresponded to 2 mph in fifth gear but also occurred at times when power was applied with the road speed too low for the particular gear.

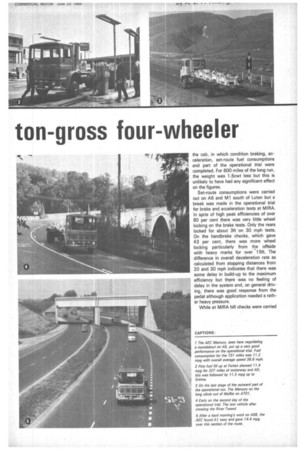

The 731-mile operational trial was completed without a hitch and as already stated very good fuel consumptions were obtained. On the motorways, the Mercury did better than expectedover 11 mpg as compared with 10.7 mpg for the set-route test. High gearing was the primary reason for these good figures--and the 14.4 mpg on Al-but the vehicle still had a more-than-adequate gradient performance with the ability to restart on 1 in 6 and have plenty in hand on even the steepest parts of A68. But with overdrive not often able to be used on the more difficult parts of the route such as A701 and A68, there was a logical drop in consumption there, particularly on A68. The reason for the low average speed between Nevilles Cross and the start of the Darlington by-pass was a big traffic hold-up with 6min needed to cover less than a mile.

The usual hill-climb checks were made on the long run. The 4.25 mile climb of Shap from the Jungle Cafe took 10min 6sec. Second gear was needed for the 1 in 9 section where the speed dropped to 10 mph. On the easier-1 in 11 /12-gradient which follows, third gear would have been possible much earlier than it was actually engaged for reasons already stated. When finally selected, road speed hovered between 15 and 17 mph for the rest of the climb.

There were not the same gear-change difficulties on Carter Bar and once down to third this was held all the way with the general speed for the 1.82 mile climb, 18 mph. The short, 1 in 9 steepest section near the top did not call for a further downward change although road speed dropped to 12 mph. Speed at the bottom had been 40 mph and after the 1 in 9, 15 mph was quickly reached at the top.

Total time for the climb was 5min 52.4sec.

With a sharp turn at the bottom, it is not possible to take a run at Riding Mill. Speed at the right-angle turn was 10 mph in second which increased to 12 mph up to the steepest, 1 in 5 gradient. Engagement of first was made with the Mercury almost stationary but the maximum in the gear-6 mph—was quickly reached and held for most of the rest of the way. Near the end of the 0.6 mile climb, a change to second was corn

pleted and the speed at the summit was 10 mph after a total climbing time of 3min 45sec.

If anything, Castleside Hill, which is just before the turn-off A68 to Consett, is more severe than Riding Mill. The hill is longer-0.8 miles—and although a run at the hill is possible, within 150yd the gradient steepens to about 1 in 5.5. Speed at the start was 38 mph and after a quick trip down through the gearbox, first was engaged with the vehicle again almost stationary. Soon after, second was engaged and the speed held at around 12 mph to within 100yd of the top where a change into third was made and 15 mph reached at the highest point. Total time for the climb was 4min 58sec.

At the end of the first day's run my shoulders ached through effort used in steering but I must have become more accustomed to driving the Mercury on the second leg. I did not have any aches at the finish and was not particularly tired. Apart from the points mentioned, I found the Mercury a good vehicle with excellent visibility and very good (standard) convex mirrors. Although specification of this type of mirror was perfectly satisfactory I had fitted a second mirror on the offside. This was a Zanetti and I wanted to assess the advantages of the unit which has two convex glasses on different planes. From the point of seeing vehicles at the rear there was no particular advantage over the convex types fitted by AEC, but there was an advantage particularly on motorways in

that the secondary glass showed up small vehicles when they were alongside and which were not visible in the normalviewing section. But I would have preferred the latter part to have been bigger instead of both parts being the same size.

Another item of special equipment that I had fitted for the test was a tachograph supplied by Smiths. The discs for the two days' operational trial are reproduced with this report and they confirm that a considerable amount of information can be obtained of a vehicle's operation with this type of instrument. The discs were not located perfectly inside the tachograph with regard to time so that that for the first day the record ran 9min late and for the second 3min early. But by taking this into account and comparing the traces with the results tabulated it is possible to pinpoint the location of the vehicle at specific times. And by studying' the speed trace the severity of particular sections of the route can be determined and where long climbs and traffic delays occurred. The zigzag trace shows mileage covered in 1-mile divisions so that total distance and average speed between points or in particular time periods can be assessed. The instrument was a two-driver type with the thick band showing the time spent at the wheel by Arthur Hollands of AEC and the thin line that by me.

List price of the Mercury chassis/cab as tested was £3,220; there were no optional fittings.