By John F. Moon, A.M.I.R.T.E.

Page 44

Page 45

Page 46

Page 47

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

A Resounding Victory

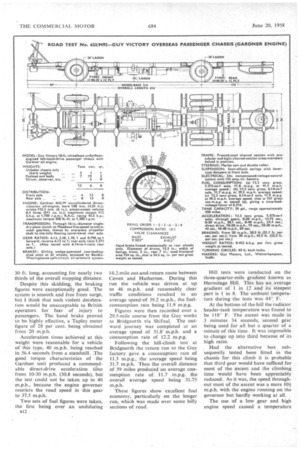

THREE series of tests were conducted with the Guy Victory Gardner-engined overseas passenger chassis, running at different gross vehicle weights and with different gearbox and rear-axle ratios. The conclusions to be drawn are that the addition of a ton payload has little effect on the remarkable fuel economy shown by the engine, whilst the higher axle ratio gives the vehicle a maximum speed of nearly 55 m.p.h., with the possibility of higher average speeds without losing anything in fuel economy.

Running at 13 tons' 6 cwt. gross, over an undulating course of more than 16 miles, 11.8 m.p.g. was returned at an average speed of 41.5 m.p.h., giving a time-load-mileage factor of 6,516—a most commendable figure. This throws a new light on the renowned economy of Gardner engines, as it shows that, despite a maximum governed engine speed of 1,700 r.p.m., a high-speed passenger' chassis can be built round the .unit, whilst the relatively low governed speed, which. gives fuel economy, n retained.

Admittedly, the use of a high axle. ratio and an overdrive-top gearbox causes some reduction in acceleration performance, but this is not of great ' importance in a chassis such as the Victory, which is primarily intended for long-distance coaching. For stagecarriage work, for which good acceleration is essential and high maximum speed of minor importanez, an extra-low-ratio axle is available..

The Victory was first introduced to the public at last year's Amsterdam 1410

Motor Show and exclusively described in The Commercial Motor on February 15, 1957. At that time it was offered as standard with the Meadows 6HDC 500 six-cylindered oil engine, which has a net output of 150 b.h.p. Because of the continued demand for Gardner engines; however, particularly in Belgium, the option of the Gardner 6HLW 112-b.h.p. unit was recently made and the chassis tested was the first one to be produced.

It is almost , identical to the Meadows-engined version, except that packing pieces have had to be interposedbetween the springs and the axles to raise the frame height slightly and thus ensure adequate ground clearance beneath the Gardner's surrip. Difference in frame height is only 1 in., giving 10+ in. sump clearance.

The Gardner engine is unit-mounted with a Meadows 350 CS5 five-speed gearbox which has Porsche synchromesh units. The standard gearbox as

used with the Meadows engine has forward ratios of 6.13, 3.38, 1.45 to 1 and 0.789 to 1, but the large gap between second and third gears, although suitable for the high-speed Meadows engine (governed at 2,400 r.p.m.), was found to be unsuited to the slower Gardner engine as originally. tested.

It was arranged, therefore, that I should have an opportunity of testing the chassis with a gearbox with an alternative third-gear ratio of 1.78 to 1. This made an appreciable difference to the performance, particularly from the driver's aspect. Other alternative gearboxes include fourand five-speed semiand fully automatic transmissions.

The Gardner-Meadows engine

gearbox unit has a three-point mounting, using spherical rubber bushes. There is a single bush on the front of the crankcase, whilst at the rear a special bell housing, designed by Guy Motors, is employed. This contains a bush at each side, through which passes a frame-mounted crosstube. This arrangement successfully cuts out any transference of engine vibration to the frame and dispenses with the need for additional damping and torque reaction linkages.

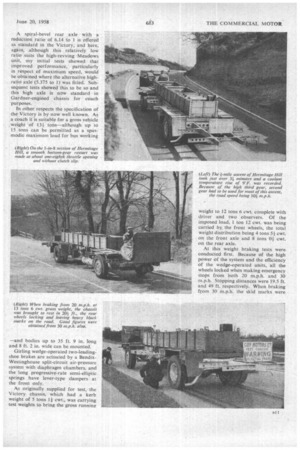

A spiral-bevel rear axle with a reduction ratio of 6.14 to 1 is offered as standard in the Victory, and here, again, although this relatively low ratio suits the high-revving Meadows unit, my initial tests showed that improved performance, particularly in respect of maximum speed, would be obtained where the alternative highratio axle (5.375 to 1) was fitted. Subsequent tests showed this to be so and this high axle is now standard in Gardner-engined chassis for coach purposes.

In other, respects the specification of the Victory is by now well known. As a coach it is suitable for a gross vehicle • weight of 134tons—although up to 15 tons can be permitted as a spasmodic rnaximumload for bus working —and bodies up to 35 ft. 9 in. long and 8 ft. 2 in. wide can be mounted.

Girling wedge-operated two-leadingshoe brakes are actuated by a Bendix Westinghouse split-circuit air-pressure system with diaphragm chambers, and the long progressive-rate semi-elliptic springs have lever-type dampers at the front only.

As originally supplied for test, the Victory chassis, which had a kerb weight of 5 tons 11 cwt., was carrying test weights to bring the gross running weight to 12 tons 6 cwt. complete with driver and two observers. Of the imposed load, 1 ton 12 cwt. was being carried by, the front wheels, the total weight distribution being 4 tons 5f cwt. . on the front axle and 8 tons 01 cwt. on the rear axle.

At this weight braking tests were conducted first. Because of the high power of the system and the efficiency of the wedge-operated units, all the wheels locked when making emergency stops from both 20 m.p.h. and 30 m.p.h. Stopping distances were 19.5 ft. and 49 ft. respectively. When braking from 30 m.p.h, the skid marks were 30 ft. long, accounting for nearly two thirds of the overall stopping distance.

• Despite this skidding, the braking figures were exceptionally good. The system is smooth and free from surge, but I think that such violent deceleration would be unacceptable to British operators for fear of injury to passengers. The hand brake proved to be highly effective, a Tapley meter figure of 28 per cent. being obtained from 20 m.p.h.

Acceleration times achieved at this weight were reasonable for a vehicle of this type, 40 m.p.h. being reached in 56.4 seconds from a standstill. The good torque characteristics of the Gardner unit produced a commendable direct-drive acceleration time from 10-30 m.p.h. (30.8 seconds), but the test could not be taken up to 40 m.ph., because the engine governor restricts the road speed in this gear to 37.5 m.p.h.

Two sets of fuel figures were taken, the first being over an undulating 812 16.2-mile out-and-return route between Coven and Hatherton. During this run the vehicle was driven at up to 46 m.p.h. and reasonably clear traffic conditions resulted in an average speed-of 39.2 m.p.h., the fuelconsumption rate being 11.9 m.p.g.

Figures were then recorded over a 29.5-mile course from the Guy works to Bridgnorth via Shifnal. The outward journey was completed at an average speed of 31.8 m.p.h. and a consumption rate of 12.2 m.p.g.

Following the hill-climb test at Bridgnorth the return run to the Guy factory gave a consumption rate of 11.3 m.p.g., the average speed being 31.7 m.p.h. Thus the overall distance of 59 miles produced an average consumption rate of 11.7 m.p.g. the overall average speed being 31.75 m.p.h.

These figures show excellent fuel economy, particularly on the longer run, which was made over some hilly sections of road.

Hill tests were conducted on the three-quarter-mile gradient known as Hermitage Hill. This has an average gradient of 1 in 1.2 and its steepest part is 1 in 8. The ambient temperature during the tests was 44'. F.

At the bottom of the hill the radiator header-tank temperature was found to be 118' F. The ascent was made in 3 minutes 34 seconds, second gear being used for all but a quarter of a minute of this time. It was impossible to change up into third because of its high ratio.

Had the alternative box subsequently tested been fitted in the chassis for this climb it is probable that third gear would have sufficed for most of the ascent and the climbing time would have been appreciably reduced. As it was, the speed throughout most of the ascent was a mere 101 m.p.h. with the engine running on the governor but hardly working at all.

The use of a low gear and high engine speed caused a temperature rise of . only 9° F. The Gardner is never a hot-running engine, so it is obvious that the cooling system is adequate for climbs which can be made at lower engine speeds and full torque output.

Two fade tests were made, the chassis being driven down the hill in neutral with the foot brake lightly applied to keep the road speed down to 20 m.p.h. Each descent lasted approximately 11 minutes and a " crash " stop from 20 m.p.h. at the bottom of the hill produced Tapley meter readings of 71 per cent. on the first occasion and 66 per cent, on the second occasion.

Good Anti-fade Brakes

These figures compare favourably with the 78 per cent. maximum retardation recorded earlier with cold drums and show the Victory, which has moulded brake facings, to have good anti-fade properties.

Returning to the 1 in 8 section of Hermitage Hill, the chassis . was stopped and the hand brake fully applied, although, because the drums were still warm, an excessive amount of pressure had to be exerted on the lever to preVent the vehicle from rolling backwards.

A smooth bottom-gear restart was then made with about one-eighth throttle opening and without clutch slip. Had the gearbox design made it possible to engage second gear when stationary I am sure that this restart could have been made in that gear without any trouble.

On returning to the Guy works the test load was increased by a ten to bring the gross weight figure nearer to the maximum recommendations of the manufacturers.

Higher Load—Better Braking

The . first test to be made at this weight was for braking efficiency and, as I had expected, appreciably better figures were obtained from 30 m.p.h., because the additional weight on the rear axle reduced the tendency towards locking. Under these conditions the stopping distance was 43.5 ft., the maximum Tapley meter reading being 74.25 per cent. From 20 m.p.h. the stopping distance was found to be 20.5 ft.—slightly greater than was obtained at the lower weight.

The difference of less than 8 per cent. between the maximum deceleration rate and the average deceleration rate showed there to be only a slight lag in the braking system, which is praiseworthy with an air-pressure layout. Hand-brake efficiency as tested from 20 m.p.h. produced a deceleration meter reading of 24 per cent.

The 1 6.2m iie fuel-consumption

route on the Coven-Hatherton-Coven road was employed again and the overall average speed was about the same as that obtained when running at 12.3 tons gross, the extra load reducing the fuel economy by a mere 0.2 m.p.g.

Similarly, there was little appreciable difference in the .acceleration times obtained with the higher loading.

Shortly after this series of tests the Victory was fitted with the higher axle ratio and the more evenly spaced gearbox ratios, the chassis weight remaining at 13.3 tons.

A difference in performance was immediately apparent in terms of ease of driving, smoother acceleration and higher maximum speed. The chassis was now capable of nearly 55 m.p.h., compared with the 47 m.p.h. obtainable with the 6.14-to-1 axle.

The usual fuel-consumption route was followed and despite much heavier traffic than was encountered during the earlier runs, the overall average speed was 41.5 m.p.h. and the fuelconsumption rate worked out at 11.8 m.p.g., showing a noticeable improvement in respect of high-speed fuel economy.

Acceleration tests revealed, as might be expected, a slightly worse performance, 0-40 m.p.h. taking 67 seconds. Had it been possible to engage second gear when stationary with the engine idling, this figure would have been improved, as was later to be confirmed. The direct-drive figures, which could be recorded up to 40 M.p.h. because of the higher-ratio axle, were adequate for the type of service envisaged for the chassis.

So far as handling is concerned, the Victory chassis attains a high standard and I was particularly pleased with the light but positive feel of the steering. Even at low speeds the chassis is easy to manceuvre and over indifferent road surfaces there is no harsh kicking at the wheel. Sufficient castor action is present.

Braking also is good, and the use of a conventional brake pedal, rather than a super-sensitive treadle, gives

fully controllable braking—an essential feature with a powerful sYstern such as this.

So far as can be judged, the suspension is good: on one of the fuel-test runs I rode in one of the weight boxes approximately midway down the chassis and could detect no uncomfortable suspension characteristics at this point. Even at the front of the vehicle the ride was reasonably smooth, although a certain amount of pitching, not unnaturally, can be felt over rough surfaces.

Although the chassis as initially tested caused me to complain about the gearbox, because of the heaviness of ale change caused by the overefficient synchromesh mechanism, the excessive gear-knob travel, the poor reverse-stop spring and the inability to engage second gear when stationary with the engine idling, I was later able to drive the Victory with a modified gearbox. This had less strong synchromesh cones, a closer gate at the base of the gear lever, a stronger reverse-stop spring, and a selector-fork modification making it possible to engage second gear for starting.

Improved Gearbox

These modifications lightened the work of gear changing without making it easy to " beat " the synchromesh when changing gear quickly. The gate successfully cut out the vagueness of the change and it might even be possible subsequently to reduce the knob travel because of the smaller leverage required by the lighter synchromesh spring cones.

Appreciably better acceleration times were recorded with the modified gearbox when the chassis was tested at 13 tons 6 cwt. gross weight. The time up to 40 m.p.h. was reduced by 12.6 seconds from a standing start when compared with the figures obtained at the same weight and with the same axle, but with the unmodified gearbox. This was partly because of the ability to start off in second gear and partly because of the quicker. changes possible with the lighter synchromesh mechanism. .

The modified gearbox had the highthird gear as originally tested, but, because of the higher axle ratio, this did not present such a disadvantage with the Gardner engine as it did when used with the 6.14-to-1 axle. Thus, it would appear that in flat countries, such as Holland, the high-third box would be satisfactory, whereas in hilly areas the low-third gearbox would be a better proposition, as the close second and third ratios would give improved h t-cl i mbing.