UNITY IS STRENGTH

Page 46

Page 47

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

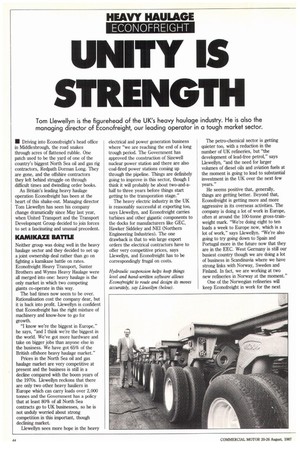

Tom Llewellyn is the figurehead of the UK's heavy haulage industry. He is also the managing director of Econofreight, our leading operator in a tough market sector.

• Driving into Econofreight's head office in Middlesbrough, the road snakes through acres of flattened rubble. One patch used to be the yard of one of the country's biggest North Sea oil and gas rig contractors, Redpath Dorman Long. They are gone, and the offshire contractors they left behind struggle on through difficult times and dwindling order books.

As Britain's leading heavy haulage operation Econofreight has been at the heart of this shake-out. Managing director Tom Llewellyn has seen his company change dramatically since May last year, when United Transport and the Transport Development Group decided to join forces to set a fascinating and unusual precedent.

KAMIKAZE BATTLE

Neither group was doing well in the heavy haulage sector and they decided to set up a joint ownership deal rather than go on fighting a kamikaze battle on rates. Econofreight Heavy Transport, Sunter Brothers and Wynns Heavy Haulage were all merged into one: heavy haulage is the only market in which two competing giants co-operate in this way.

The bad times now seem to be over. Rationalisation cost the company dear, but it is back into profit. Llewellyn is confident that Econofreight has the right mixture of machinery and know-how to go for growth.

"I know we're the biggest in Europe," he says, "and I think we're the biggest in the world. We've got more hardware and take on bigger jobs than anyone else in the business. We have got 65% of the British offshore heavy haulage market."

Prices in the North Sea oil and gas haulage market are very competitive at present and the business is still in a decline compared with the boom years of the 1970s. Llewellyn reckons that there are only two other heavy hauliers in Europe which can carry loads over 2,000 tonnes and the Government has a policy that at least 80% of all North Sea contracts go to UK businesses, so he is not unduly worried about strong competition in this important, though declining market Llewellyn sees more hope in the heavy electrical and power generation business where "we are reaching the end of a long trough period. The Government has approved the construction of Sizewell nuclear power station and there are also coal-fired power stations coming up through the pipeline. Things are definitely going to improve in this sector, though I think it will probably be about two-and-ahalf to three years before things start getting to the transporation stage."

The heavy electric industry in the UK is reasonably successful at exporting too, says Llewellyn, and Econofreight carries turbines and other gigantic components to the docks for manufacturers like GEC, Hawker Siddeley and NE! (Northern Engineering Industries). The one drawback is that to win large export orders the electrical contractors have to offer very competitive prices, says Llewellyn, and Econofreight has to be correspondingly frugal on costs. The petro-chemical sector is getting quieter too, with a reduction in the number of UK refineries, but "the development of lead-free petrol," says Llewellyn, "and the need for larger volumes of diesel oils and aviation fuels at the moment is going to lead to substantial investment in the UK over the next few years."

He seems positive that, generally, things are getting better. Beyond that, Econofreight is getting more and more aggressive in its overseas activities. The company is doing a lot of work in Europe, often at around the 100-tonne gross-trainweight mark. "We're doing eight to ten loads a week to Europe now, which is a lot of work," says Llewellyn. "We're also going to try going down to Spain and Portugal more in the future now that they are in the EEC. West Germany is still our busiest country though we are doing a lot of business in Scandinavia where we have strong links with Norway, Sweden and Finland. In fact, we are working at two new refineries in Norway at the moment."

One of the Norwegian refineries will keep Econofreight in work for the next two years at least. Llewellyn sees France as the biggest thorn in his side, internationally: 'The French are still tricky to deal with on abnormal load permits," he says.

How does Econofreight sell its wares on the Continent? "We have a lot of highly professional salesmen," says Llewellyn. "They are all engineers and they have all been trained on the ground. They know exactly what they are talking about. We also do our own market research, and we usually do a desk study project on a target area, like a new refinery, and try and work out who is likely to win the job." A lot of this work is highly speculative, and Econofreight uses all of its contacts and experience to try and target the winning companies when the tendering race is on.

FLY THE FLAG

Llewellyn likes to be patriotic too. "Overseas," he says, "we fly the flag." He frequently does work for major and successful international British management contractors like Foster Wheeler, "perhaps for free". This is done at the planning stage in the hope that when the contractor has won the job using Econofreight's transportation figures, Econofreight gets the transport subcontract. He freely admits, however, that "construction companies can be the worst people to work for". He is not really interested unless the load is well over 100 tonnes, otherwise the competition brings margins down too far. The Channel Tunnel project does not thrill him either: "Most of the stuff is going to be too small for us to bother with," he says. Econofreight has a fleet of 83 vehicles and the capacity to carry up to a single, indivisible load of 7,000 tonnes. Next year a major offshore contract will use that full 7,000-tonne capacity in one great move. "We can also carry 70 100-tonne loads simultaneously," says Llewellyn. His fleet goes from 38-tonne 'normal' tractor units to 500-tonne drawbar tractors "most of which", he says, "are Scan-miens." Laden at 100 tonnes gross, they return a consumption of 94 to 71 lit/100km.

There are also Dais, Mercedes-Benz, Volvos and Scanias in the fleet.

Llewellyn is unhappy about the question mark hanging over Scammell. "We would prefer to be loyal to Scammell," he says, and he likes the 524 and S26 Contractor units that he runs, but "I cannot, and I will not let my company become a hostage to Scanunell's fortunes." A number of the Scammells now need replacing and Llewellyn faces a dilemma — he can either replace or refurbish them. On the trailer front Llewellyn says that he wants to standardise his hydraulicallysteered multi-axle fleet on Nicolas of France. The Nicolas units come in fouror six-axle chunks which can be bolted together. For multi-axle step-frames and low loaders, Llewellyn has a soft spot for King trailers.

Hydraulic trailer suspensions keep scrub damage low and Econofreight gets all of its cold-cap retreads from a local company called Summit run by Peter Palmer, an ex-Michelin manager. Llewellyn likes the personal service he gets from Summit.

As chairman of the Road Haulage Association's heavy haulage group, he also takes an overview. He thinks "we are substantially under-investing in our roads, ferry ports and motorways." The Transport Secretary is a "Cinderella post" and 40 tonnes should be brought in as soon as possible.

He has his doubts about the weak bridges argument. The strength of lashing points on trailers concerns him, as do the new, comprehensive Special Types regulations. He is opposed to higher road speeds for heavy loads, for instance: "Our men will be told not to use them," he says. Also, Our 43-tonne Scarnmells come under the special types regs when they run empty — it's ridiculous." 0 by Geoff Hadwick