Road Test of C ler Maxiload

Page 58

Page 59

Page 60

Page 61

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

0 F the new models at the last Commercial Motor Show, one of the more interesting was the Commer Maxiload, as its introduction there marked the entry of Rootes into the maximum-gross-weight four-wheeler field. This was all the more significant because the increase in permitted maximum gross weight to 16 tons had only just been announced.

I recently tested a 16-ion-gross model and could not see any point on which the model can be really criticized. Handling and the standard of cab comfort were excellent, as were the fuel-consumption figures obtained. The general standard of performance was very high and the braking very good, although build-up delay in the airpressure system made the stopping distances obtained only of an average standard.

In appearance, the Maxiload is a soundly and robustly constructed vehicle and looks well able to do the job it is designed for. There is little variation in specification between the 14and 16-ton-g.v.w. versions. The frame and mechanical units are the same, but the tyre equipment and the ratio of the standard single-speed rear axle differ. An identical two-speed rear axle is an option. There is also a change in the suspension design. .

Both version of the Maxiload are available in three wheelbases-12 ft. 11 in., 14 ft. 8 in. and 17 ft. 11 in.—and these are suitable for bodies of 14 ft. (tippers), 16 ft. 6 in. and 21 ft. respectively. It was the long-wheelbase model ' that was supplied for the road test and this had a Campion 21ft.-long, triple-drop-side light-alloy body.

A higher-power version of the Rootes three-Cylinder, two-stroke, opposed-piston diesel engine, the 3D.215, was developed for the Maxiload and this gives a maximum net output of 132 b.h.p. at 2.400 r.p.m. and a maximum net torque of 335 lb. ft. at 1.250 r.p.m. The output compares with 102 b.h.p. and 114 b.h.p. produced by two other versions of the Rootes engine used in Commer vehicles and results from an increase in bore size from 3.25 in. on the earlier units to 3-375 in. This increases capacity from 199 cu. in. to 215 cu. in.

With the increase in bore size and output there were also modifications made to the fuel pump to get an increased delivery, a larger oil cooler was fitted and the diameter for the shafts carrying the rockers which transfer the piston and connecting rod movements to the crankshaft was increased.

The Maxiload was fully described in The Commercial

or at the time of its introduction on September 11, The general design of the Todd followed that of ighter-weight Commer chassis produced, although an Dyed cab is fitted as standard, this being called the ry-Plus. Whilst there are some small modifications nally, such as repositioning the twin headlamps, most e improvements are inside, where the degree of trim been increased and there are no metal parts in nee. Framing round the windscreen and doors is .ed by plastics material and the soft, perforated head has a felt backing. The top and bottom of the facia I are well padded with foam and a plastics covering, he rubber floor-covering is foam-backed.

two-passenger seat is standard and the driver's seat mproved, it being now fully adjustable for rake of the squab as well as having fore-and-aft and seat-height trnent. The driver's seat has adjustable torsion-loaded !nsion and standard equipment in the cab includes screen washers, padded sun vizors and large ashtrays ath doors, amongst other things. Worthwhile standard iment for the UK market is a 4.65 kW heater.

cation of the engine in a similar position to that ted on other Commer chassis in which the Rootes is used brings it below the rear half of the cab and r the seat support pressing, leaving a flat floor across richt' of the cab. The drive from the engine is taken igh an hydraulically-operated clutch to a Commer peed synchromesh gearbox as standard. with an addi1 sixth overdrive ratio as in the test vehicle available I option. This is the same basic box with identical ird and reverse ratios; the overdrive is.provided by an section at the rear of the casing which gives the ional 0-787 to I ratio. The front and rear axles have 6and 10-ton-capacity units respectively for the n-gross machine and the same components appear in pecification of the 14-tonner. But the Eaton 1800 lard single-speed rear axle is available with a ratio 5 to 1 only on the 16-ton model and 5.57 to l'on'the 14-ton version. When the optional Eaton 18802 two-speed rear axle option is specified—as on the test vehicle—the ratios are 5-57 and 7-60 in both cases, Hydraulic powerassisted steering is standard on the Maxiload, the steering box being a Cam Gears cam-and-peg unit with a ratio of 24.5 to I.

Basically, the main members of the frame on the Maxiload are the same section as the Commer 8-tonner-9.75 in. deep with a 2.625 in. top flange and a 3.06 in. bottom flange. But external flanged flitches are fitted to both members and these provide an extra bcittom flange 3-28 in. wide and extend the full depth Of the side-members to make an effective overall depth in-the area of the flitches of 12-5 in. The flitch plates extend from the front-spring rear-hanger brackets to the centre line of the rear axle.

The front and rear brakes of the full air-pressure system are on separate circuits and Westinghouse components are used, including a dual-concentric foot valve and twochamber reservoir. At the rear brakes actuation is by Westinghouse dual-diaphragm chambers, and there has been a change here since the Maxiload was first introduced, 30/30 units now being used instead of 24130. The secondary side of these provides the emergency-brake requirements of the new C. and U. regulations being pressurized on application of the handbrake by a control valve at the lever fulcrum.

There has also been a recent change in tyre equipment 10.00-20. 16-ply or radial-steel-cord tyres can be fitted. having been up-rated, to carry 6 tons when on the front' axle of a plated vehicle.

For the tests' the Commer carried a load of gravel and a few concrete weights totalling in all 10 tons 9 cwt. With the kerb weight of 5 tons 8-5 cwt. this brought the gross_ weight to just under the 16-ton limit with the driver only in the cab. But with two passengers on board, the limit was exceeded by 2 cwt. All the tests were carried out at this weight except for the unladen fuel consumption runs. and the Maxiload put up a roost creditable performance. As 16-ton-gross four-wheelers are a fairly new breed. there is no 'standard with which to compare the figures obtained for consumPtion and acceleration performance with the Maxiload. But the consumption figure of 12-8 m.p.g. for a run when cruising at around 40 m.p.h. will stand comparison with most 14-ton-gross vehicles tested previously by Tlie Commercial Mawr and is considerably better than figures obtained with vehicles running at a similar gross weight which, of course, have been sixwheelers or artics. When running empty the fuel consumption figures were somewhat remarkable: 24-0 m.p.g. at 30 m.p.h. and 18-7 m.p.g. at up to 40 m.p.h.

It was interesting that on the motorway runs there was not so much difference between the figures when laden and unladen-10-8 m.p.g. and H-4 m.p.g. respectively. But the average speed attained showed a worthwhile increase when unladen----54-7 m.p.h. .against 48.8 m.p.h. The section of M I used for the high-speed runs was the usual one when testing in the Luton area, from the end of the spur to the A15. down to the A4I47 and back. The total distance is /5.2 miles and because the distance to and from the main o2'

stretch of MI at the Luton end and the section getting off the motorway and back on to it at the A4147 are fairly long it means that fuel consumption figures obtained are lower than one would get on extensive motorway running. This is shown up by the fact that although when on the main stretch the Maxiload was running at its maximum of about 70 m.p.h.. the best average unladen was 54-7 m.p.h.

The reason for the closeness of the consumption figures is obviously because of the major part of the fuel being used to overcome air resistance at the very high speed. At no time on the laden run was the vehicle out of overdrive and the speed did not drop below 40 m.p.h. on fairly severe stretches. When unladen the maximum speed was the same and did not go below 50 m.p.h.

Certainly the Maxiload will be hard to beat for fuel consumption and whilst the figures quoted are for all-laden running. when running full one way and empty the other such as on most C-licence operation-consumptions of between 15 and 18 m.p.g. should be attainable.

Much of the credit for the excellent fuel consumption must' be put down to-the use of an overdrive gearbox. but

vehicles tested with this feature have not given such results. It is becoming increasingly obvious from :sts that the use of an overdrive unit brings so many tages that the additional cost that this normally —£30 on the Maxiload—is well worth while.

ler at ion performance results were also very good .tre again the figures obtained were well up to the rd of earlier 14-ton-gross vehicles tested. On the drive runs the high rear-axle ratio was engaged and gh this was expecting a lot, a good pull-away from ■ .h. and lower was made without distress.

already stated, the stopping distances obtained on iximum-pressure brake tests, whilst good, would have mproved if there had been less delay in the system. was no indication of excessive lag in applying the ,-that is, as soon as the pedal was depressed there ;action from the brake units -but the indication was D me time was taken to build up to full pressure at mating chambers. In fact, the figures obtained do Justice to the excellent design of the brakes, as on all ips light and even marks were left on the road surface th the front and rear tyres. This indicated that the

was perfect between the front and rear.

was the best vehicle for actual braking performance have so far tested.

degree of delay before full-pressure build up was ited by the length of the lyre markings on the road, measured about half the total stopping distance 30 m.p.h. With an improvement in this respect ionally good figures should be obtained, and instead actual efficiencies, based on stopping distance, of

50 per cent. actual efficiencies close to the maxiJecelerations of 75 per cent from 20 m.p.h. and 77 per 'om 30 m.p.h. indicated by Tapley Meter could result. gure of 41 per cent quoted in the results panel for rake efficiency is also, of course. that for the ency brake system as this is brought in on application handbrake which allows air to the rear-brake dual.agm chambers. The figure is well up to standard.

ci Hill-Climbing Performance

ery good performance was put up by the Maxiload on ,mbing performance tests which were carried out on 75-mile-long Bison Hill. Here the average gradient ri IV and a maximum-power ascent was made in lad time of 4 min 21.8 see. The lowest gear used was eith high-axle ratio engaged, in which I min. 8.4 sec. )ent, and the minimum speed was 4 m.p.h. Because axiload engine-cooling system incorporates a header it was not possible to obtain accurate measurements e increase in coolant temperature, but with the nt temperature 22 C (72' F) there was no appremovement in the temperature gauge.

ke fade was assessed on a run down the hill with of the run being made in neutral with the brakes d to keep the speed at 20 m.p.h.; towards the bottom the hill levels out, engaging direct drive (high-axle and with full throttle applied, the brake kept on to he speed to the same figure. A maximum-pressure stop from 20 m.p.h. at the bottom of the hill produced tpley-meter reading of 67 per cent. Total time for the it had been 2 min, 26 sec., with 31 sec. spent driving

the brakes, and the small reduction in efficiency n 75 per cent with cold drums—proved that the oad should give no problems with fade.

)-and-restart tests were carried out on the steepest a of Bison where the gradient is 1 in 6-5. No trouble was experienced in starting off when facing up the id in reverse when facing down, with the high rearalio engaged in both cases, And in both conditions tndbrake held the vehicle easily.

h the combination of the six-speed overdrive gearbox wo-speed rear axle. 12 distinct forward ratios are although in some cases these are close together. s shown up by the maximum sneeds obtainable in trious gears which were obtained on the motorway. low-axle ratio engaged these were 3, 8. 15, 24. 39 and 50 m.p.h., whilst with the high-axle ratio the maximum speeds were 6, 13, 21, 34, 54 and 70 m.p.h. From this it will be seen that to get split changing in the higher ratios the change sequence from fourth-high is fifth-low, then sixth-low, fifth-high and sixth-high.

From a handling point of view, I found it impossible to fault the Maxiload. All the controls are well placed and require little effort to operate. The power-assisted steering is near-perfect, being light but not excessively so, so that it had a very positive feeling with none of the vagueness often met with on vehicles having this feature. There was, in fact, no impression that the steering was power-assisted and the feeling was more like driving a much lighter vehicle with normal steering. This was also the case when driving the test vehicle unladen, when there was still sufficient " feel There was also good braking response from the pedal, although without a load 1 found it difficult initially to produce the exact degree of braking for particular circumstances.

Lively Vehicle

The good figures obtained on the acceleration and hillclimbing tests were reflected in the general performance of the Maxiload, which was quite lively with adequate power provided by the engine. I expected this as the last test did of a Commer was the lit-ton-gross tractive unit, and although this was fitted with the Rootes 3D.199, 114 b.h.p. three-cylinder diesel and the power/weight ratio was only 6 b.h.p. per ton compared with 8.3 b.h.p. per ton of the Maxiload, it still gave a very good general performance. It is certainly true that the use of the Rootes diesel usually endows a vehicle with a good performance and, at the same time, very good fuel economy. And it is worth mentioning that, although introduced more than 10 years ago, this engine is still the most unconventional fitted to British commercial vehicles.

Besides being standard on the Maxiload, the Luxury-Plus cab is optional on Commer 8-ton and heavy-duty 7-ton models when fitted with the Rootes diesel; on these two chassis the extra cost incurred is £60. Although the first step height (forward of the front wheels), at 2 ft. 2.5 in from the ground when the vehicle is laden, makes entry into the cab a bit of a stretch, access is relatively easy and, of course, on a I6-ton-gross machine the driver is not gelling in and out of his seat very frequently; grab handles on the forward windscreen pillars on both sides are a useful addition. The standard of interior fittings and trim is very high and the unit is well insulated against engine noise, allowing normal conversation even when running at maximum speed. For normal running, the fitting of the optional overdrive shows its value. In addition to giving improved fuel consumption the engine noise is very inconspicuous al up to 40 m.p.h.

I found all-round visibility quite good but was not happy with the mountings for the rear-view mirrors. These are on U-shaped brackets bolted to the doors and the need for an additional stay was shown by the mirrors often vibrating.

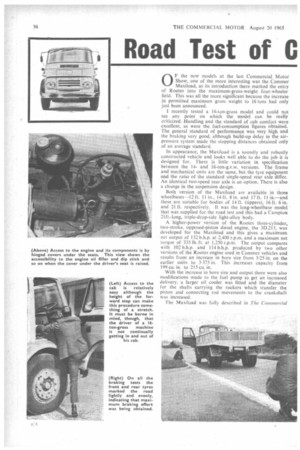

As the cab is a fixed unit, access to the engine and components is provided by hinged covers under the seats— the seats are actually mounted on these and are hinged themselves so that the cushion frame is raised with the covers also. Getting to the engine is not difficult, merely requiring the bringing forward of the seat cushions and undoing simple catches before the covers are raised. Routine jobs, such as checking engine oil and the levels of the reservoirs fm the power-assisted-steering hydraulic system and hydraulic-clutch system. require the raising of the cover below the driver's seat, whilst the larger one under the passenger seat only needs to be raised for relatively rnaior work on the engine.

The basic price of the Commer Maxiload tested is £2.455 for the chassis and cab, plus £30 for the overdrive and £95 for the two-speed axle option (both these units are well worth the money). The price of the Campion light-alloy body is £515, which includes fitting, bringing the total cost of the test vehicle to £3,095.