WHEN EVERY . SECOND YUNT S

Page 58

Page 59

Page 60

Page 61

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Power, Speed and Good Traction Combine ti Thornycroft 6 x 6 Crash-tender Chassis with B81 Engine an Invaluable Asset for flirfie

By' John F. Moon,

WHATEVER may be said in favour of the oil engine on the grounds of economy, power and longevity, when it comes to getting over the ground quickly the petrol engine still reigns supreme. Fit a petrol engine to a pedigree cross-country chassis having six-wheel drive and the result can be a vehicle that will• Maintain a high speed irrespective of the terrain.

This formula has been adopted by Transport Equipnient (Thornyeroft), -Ltd., in their Nubian TA. B81 6, x 6,fire7crash tender, and during two days' thorough testing, on and off the road, it showed itself • to have an exceptionally high performance and fully to .jdstifY the—makers' claims for its popularity on airfields all over the world: indeed, on certain sections of the alpine course at Bagshot Heath the 'chassis succeeded .

-negotiating obstacles which the factory .representatives who were with me were convinced it would never be able to manage.

The Nubian 6 x 6 is a logical development of the 4 x 4 chassis, which was used in large numbers during the 193-45 war and•which is still in production in a slightly modified form. Both chassis embody the same basic design principles, but the introduction of a third axle has necessitated the adoption of a different type of suspension system. .This conSists of two semi-elliptic springs on each side of the chassis, one above the other, which are linked to the axles by X-shaped brackets, the springs being independently pivoted at their centres to large, heavily webbed brackets.

The X-shaped brackets are joined by trunnions to the axles and at their -extreme ends carry chromiumplated pins which have approximately .1 in. sideways lateral free play in the spring eyes. The result is a flexible form of bogie suspension which ensures maximum traction under all conditions, at the same time contributing towards reduced tyre wear.

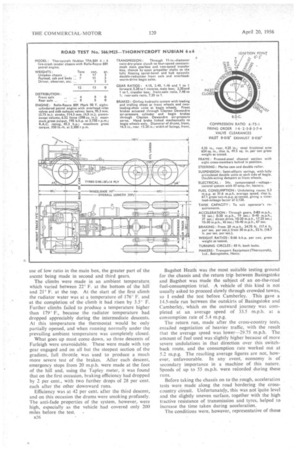

There are four types of Nubian 6 x 6 chassis at present being manufactured, and that selected for the test was powered by the Rolls-Royce B81 Mark• 50F eight-cylindered in-line petrol engine. This chassis is generally similar to the military version, which differs in having a B81 Mark 5Q engine and a heavier transfer box. Another military ,model of the chassis with a

n24

similar transfer case has th-e lower-powered B80 petrol.

engine. .

All these chassisare eminently suitable for highspeed work such as 'would be expected from fire-crash appliances, but, where economy is more important than

speed, oil-engined -version, using the Thornyoroff CRS6 90 b.h.p. six-cylindered engine; iS available.

This vehicle has a maximum speed of 45 m.p.h., compared with the 69 m.p.h. of the B81-engined version, but gives a reduction in fuel-consumption rate of about' 40 per cent. and has, therefore, many uses in construction work, especially in connection with oilfields.

The front axle is a spiral-bevel and hub epicyclic-gear double-reduction Unit, which is common to the 4 x 4 chassis and has a slightly lower ratio than the overheadworm-drive bogie axles. This difference in ratio has, been found advantageous in that it tends to give a greater concentration of tractive effort on the bogie axles.

When I sicked up the 6 x 6 from the Thornycroft works I could foresee two rather cold days ahead of me, as the average ambient temperature during that week was in the region of 21° F. and no cab or bodywork was fitted to the chassis. [This report has been delayed by the printing dispute]. Slight protection was afforded

by a canvas screen and small windscreen. The standard cab which can be supplied with the chassis is similar to the usual Thornycroft all-steel assembly, but is wider and has a small external radiator cowl.

The unladen weight of the chassis had previously been determined at 4 tons 17.1-, cwt. and 7 tons 11i cwt. had been added in the form of a test load to bring the total weight, less driver and passengers, to 12 tons 91, cwt. This is the normal recommended gross weight for the chassis and is equivalent to a completely equipped fire-crash tender with full tanks. The load had not been placed in a special position on The chassis frame, but, as the figures. in. the data table show, the weight distribution was almost ideal.

A quiet level stretch of foad between Basingstoke and Andover was found suitable for the brake tests, and, although it appeared to be dry, the skidding which resulted when making emergency stops suggested that there was a certain amount of frost still present on the surface.

During each stop there was commendably little time lag noticeable in the system and only light pedal pressures were required; further pressure had no beneficial effect. The stopping distances achieved would have been much improved had the bogie Wheels not locked, the length of the skid marks being approximately three-quarters of the total distance taken to come to a rest. From both 20 m.p.h. and 30 m.p.h. the Tapley meter registered 100 per cent., showing a high initial rate of deceleration before skidding occurred.

As is customary with Thornycroft road tests, Farleigh Hill was the scene of the hill climb and brakefade tests.The hill, which starts at Cliddesden, is 1.4 miles long and has an average gradient of 1 in 27 with a maximum of 1 in 8.4. Three climbs were made to discover the best time in which the hill could be scaled, and the works' driver and I took turns at driving.

The fastest time was 3 min. 6 sec., which gives an average speed for the climb of 27.1 m.p.h., which, I was given to understand, is one of the highest speeds ever recorded. High ratio in the auxiliary box was used for all these climbs and the steepest section required brief use of low ratio in the main box, the greater part of the ascent being made in second and third gears.

The climbs were made in an ambient temperature, which varied between 22° F. at the bottom of the hill and 21° F. at the top. At the start of the first climb the radiator water was at a temperature of-176' F. and at the completion of the climb it had risen by 3.5° F. Further climbs failed to produce a temperature higher than 179° F., because the radiator temperature had dropped appreciably during the intermediate descents. At this temperature the thermostat would be only partially opened, and when running normally under the prevailing ambient temperature was completely closed.

What goes up must come down, so three descents of Farleigh were unavoidable. These were made with top gear engaged and on all but the steepest section of the gradient, full throttle was used to produce a much more severe test of the brakes. After each descent, emergency stops from 20 m.p.h. were made at the foot of the hill and, using the Tapley meter, it was found that on the first occasion, braking efficiency had dropped by 2 per cent., with two further drops of 28 per cent. each after the other downward runs.

Efficiency was at 42 per cent. after the third descent, and on this occasion the drums were smoking profusely. The anti-fade properties of the system, however, were high, especially as the vehicle had covered only 200 miles before the test. 1326 Bagshot Heath was the most suitable testing ground for the chassis and the return trip between Basingstoke and Bagshot was made the subject of an on-the-road fuel-consumption trial. A vehicle of this kind is not usually asked to proceed slowly through crowded towns, so 1 ended the test before Camberley. This gave a 14.5-mile run between the outskirts of Basingstoke and Camberley, which on the outward journey was completed at an average speed of 33.5 m.p.h. at a consumption rate of 5.4 m.p.g.

The return run, made after the cross-country tests, entailed negotiation of heavier traffic, with the result that the average speed was lower-29.75 m.p.h. The amount of fuel used was slightly higher because of more severe undulations in that direction over this switchback route, and the consumption rate worked out at 5.2 m.p.g. The resulting average figures are not, however, unfavourable. In any event, economy is of secondary importance in a machine of this nature. Speeds of up to 55 m.p.h. were reCorded during these ru ITS.

Before taking the chassis on to the rough, acceleration tests were made along the road bordering the crosscountry circuit. Unfortunately, this was not 'quite level and the slightly uneven surface, together with the high tractive resistance of transmission and tyres, helped to increase the time taken during acceleration.

The conditions were, however, representative of those to be found on most aerodromes, so my figures can be taken as a fairly accurate guide to the flat-out performance of the chassis. I was particularly pleased to see that acceleration from 8 m.p.h. in top gear was smooth, this remark applying to the transmission as Well as to the engine, which, running on basic-grade fuel, emitted no sounds of pinking.

Several rounds of the bumpy overseas course were made on the heath before we took the chassis on to the alpine course. The ground was rock-hard and after one tentative circuit the tyre pressures were reduced from 55 p.s.i. to 30 p.si, resulting in a much more comfortable ride. The overseas course incorporates several washboard and witching-wave sections, which, at speed, frequently caused the front wheels to leave the ground. I give the suspension full marks for its performance on this circuit.

There was no water on the circuit, so the fording capabilities of the 6 x 6 could not be put to the test, but I am assured by the makers that in standard trim (as tested) it is capable of negotiating 2 ft. 6 in. of water, and that little modification is required to take it through 4 ft.

The alpine course held no terrors for the Nubian and it was taken over several sections which had not been used by the makers during their previous tests of this type of chassis. One particular gradient of I in 31 is rarely scaled by vehicles of this size, hut, partly because the ground was hard and tightly packed, several successful low-gear, low-ratio climbs were completed,

to the surprise of the works representatives. Lower down the same slope, where the gradient meter registered

in 4.25, a stop-start test was made, but the handbrake gave signs of requiring adjustment, as it only just managed to hold the chassis.

Full Traction

During all these tests pronounced wheel-spin never became apparent and it was obvious that full traction was always being obtained at all wheels. The good suspension contributed towards ease of gear-changing over the roughest of surfaces, but I cannot say that I was pleased with the steering, which gave some hefty kick-backs on rough ground and, despite the low gearing, required excessive effort, especially when sharp turns at speed became necessary.

Even with tyre pressures up to normal when on the open road, the steering was still not light and all the arguments pointed to some form of power assistance. This would not only reduce the effort required, but would also eliminate most of the kick-backs on rough ground.

Maintenance tests were principally confined to level checks, of which quite a few are required on a six-wheel drive machine with two gearboxes. To check the radiator-water level, but not allowing for any shrouding which would possibry be fitted by the bodybuilders, occupied 4 sec., but checking the engine oil level was not so easily accomplished. There was a badly fitting panel in the side of the bonnet which took a long time to replace, and the dipstick orifice in the side of the crankcase was almost impossible to see and reach.

The gearbox oil level was ascertained by means of the dipstick in 27 sec. Checking the oil level in the transfer box was done in 35 see., there being a combined filler and level plug in the near side of the box which is easily reached from underneath the chassis. The bogie axles also have combined filler and level plugs and these levels were checked in 53.5 sec. and 43 sec., respectively. Separate filler and level plugs are used at the front axle and each of these was removed and replaced in 50 sec.

Checking Brake Fluid

There are two brake fluid reservoirs because of the two separate master cylinders used in the system, and in their exposed position on the chassis, checking their levels occupied only 22/ sec., although by the time the bodybuilders were finished the reservoirs might not be so easy to reach.

Another level check, highly recommended by the manufacturers, is that of the oil in the air-compressor sump. The dipstick for this can be reached by removing the side-valance panel, which takes 15 sec. to detach and 15 sec. to replace. Checking the level by the screwtopped dipstick was a 37-sec. job.

I had intended to change the petrol-filter element, but the securing nut was sealed so I did not interfere with it. Similarly, I did not attempt any maintenance on the engine, because there is a rule at Basingstoke that only Rolls-Royce engineers should handle their engines while the chassis is still at the works. Adjusting the brakes is a 15-min. job, each brake back-plate having one hexagon adjuster.

As is usual with Thornycroft vehicles, an extremely comprehensive tool kit is issued, to which is added a separate kit of special tools for the Rolls-Royce engine. The high standard of the tool kit alone reflects the quality which is built into this chassis—a quality which is most essential in a fire appliance when seconds may cost lives.