• The trend towards more power is no longer confined

Page 36

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

to tractors. A flurry of high-powered eight, six and now fourwheeler chassis have entered the market and on today's congested roads that can be no bad thing, enabling late trucks to make up time. But do these wagons really make economic operating sense?

For tractors, the power leaps have been roughly between 216kW (290hp) and 268kW (360hp) for fleet trucks, and anything between 246kW (330hp) and 313kW (420hp) to first 347kW (465hp) and now anything up to 373kW (500hp). Current 354kW (475hp) flagships have a power-toweight ratio of around 9.32kW/tonne (12.5hp/tonne), and similar power-toweight ratios for fourwheelers are now • being achieved by MercedesBenz with its 1721, lveco Ford with its Cargo 1721, Renault with its G200.17D — and now by ERF with its E8.21.

Both the British-built trucks have emerged as a product of Cummins development. The charge-cooled, uprated B-Series and the downrated, turbochargedonly C-Series gave birth to models designated .18 and .21 from each manufacherer The creation of this new power sector is not a British preserve, however. Steyr and now Mercedes have their An circa-1 5 7kW (210hp) engines, and others are actively engaged in designing similar wagons.

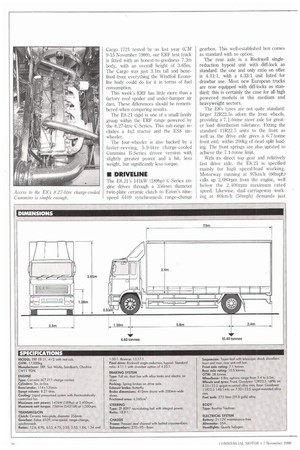

Unlike the ultra-aerodynamically bodied Cargo 1721 tested by us last year (CM 9-15 November 1989), our ERF test truck is fitted with an honest-to-goodness 7.3m body, with an overall height of 3.65m. The Cargo was just 3.1m tall and benefited from everything the Windfoil Econolite body could do for it in terms of fuel consumption.

This week's ERE has little more than a factory roof spoiler and under-bumper air dam. These differences should be remembered when comparing results.

The E8.21 rigid is one of a small family group within the ERF range powered by the 8.27-litre C-Series. This sub-range includes a 4x2 tractor and the ES8 sixwheeler.

The four-wheeler is also backed by a faster-revving, 5.9-litre charge-cooled Cummins 13-Series driven version with slightly greater power and a bit, less weight, but significantly less torque.

The E8.21's 141kW (189hp) C-Series engine drives through a 356mm diameter twin-plate ceramic clutch to Eaton's ninespeed 6109 synchromesh range-change gearbox. 'This well-established box comes as standard with no option.

The rear axle is a Rockwell singlereduction hypoid unit with diff-lock as standard: the one and only ratio on offer is 4.11:1, with a 4.33:1 unit listed for drawbar use. Most new European trucks are now equipped with diff-locks as standard; this is certainly the case for all high powered models in the medium and heavyweight sectors.

The E8's tyres are not quite standard: larger 12R22.5s adorn the front wheels, providing a 7.1-tonne steer axle for greater load distribution tolerance. Fitting the standard 11R22.5 units to the front as well as the drive axle gives a 6.7-tonne front end; within 200kg of dead split loading. The front springs are also uprated to achieve the 7.1-tonne limit.

With its direct top gear and relatively fast drive axle, the E8.21 is specified mainly for high speed/load working. Motorway running at 97km/h (60niph) calls up 2,080rpm from the engine, well below the 2,400rpm maximum rated speed. Likewise, dual carriageway working at 80km h (50mph) demands just 1,730rpm right in the middle of the green band. Slower speed running is not a problem thanks to the nine-speed box.

ERF has wisely chosen to drop the six speeder from the options list in case someone specifies it while trying to save a ha'p'orth of tar and spoils the ship in the process.

Endowed with this much power, the E8.21 will romp along at any pace the driver chooses and traffic or the law allow.

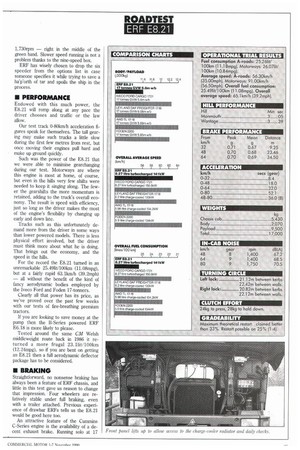

Our test track 0-80km/h acceleration figures speak for themselves. The tall gearing may make such trucks a little slow during the first few metres from rest, but once moving their engines pull hard and make up ground quickly.

Such was the power of the E8.21 that we were able to minimise gearchanging during our test. Motorways are where this engine is most at home, of course, but even in the hills very few shifts were needed to keep it singing along. The fewer the gearshifts the more momentum is retained, adding to the truck's overall economy. The result is speed with efficiency, just so long as the driver makes the most of the engine's flexibility by changing up early and down late.

Trucks such as this unfortunately demand more from the driver in some ways than lower powered models. There is less physical effort involved, but the driver must think more about what he is doing. That brings out the economy, and the speed in the hills.

For the record the E8.21 turned in an unremarkable 25.491ff/100km (11.08mpg), but at a fairly rapid 63.11mA (39.2mph) all without the benefit of the kind of fancy aerodynamic bodies employed by the Iveco Ford and Foden 17-tonners.

Clearly all that power has its price, as we've proved over the past few weeks with our tests of fire-breathing premium tractors.

If you are looking to save money at the pump then the B-Series powered ERF E6.18 is more likely to please.

Tested around the same CM Welsh middleweight route back in 1986 it returned a more frugal 23.1lit/100km (12.24mpg), so if you are bent on getting an E8.21 then a full aerodynamic deflector package has to be considered.

Straightforward, no nonsense braking has always been a feature of ERE chassis, and little in this test gave us reason to change that impression. Four wheelers are relatively stable under full braking, even with a trailer attached. Previous experience of drawbar ERFs tells us the E8.21 would be good here too.

An attractive feature of the Cummins C-Series engine is the availability of a decent exhaust brake. Running solo at 17 tonnes it has the effectiveness of the average retarder. Even on fast motorway descents it was able to check our speed, keeping within 97km/h (60mph) without resorting to the brakes.

Again our experience of a similarly engined drawbar chassis tells us the exhaust brake effectiveness is just as useful at higher weights.

The specific tests at MIRA again revealed nothing unusual. There was minimal delay between pedal application and the start of retardation. It is noticeable from the MotoMeter charts how the rate of build-up increases as the asbestos-free linings warmed up during the three tests.

The E8.21 comes with the rest bunk cab as standard and the usual sleeper cab available as an option. The day cab is generally not available, but in these days of manufacturing over-capacity and increased competition most things are possible at a push.

The cab has the standard layout, though the revised dashboard design which first appeared at the NEC Show was not fitted to our test truck. Evidently it is being fitted in the tractors first.

When it's time to get some shuteye in the rest cab the driver simply moves both seats forward to their maximum travel then folds down the bunk, which is split along its length and is normally stowed away against the rear cab wall.

Having slept in an ERF rest cab we can confirm that the bunk is comfortable enough, although you'd probably not want to spend too many nights away from home in one. Again it's a case of the employed driver probably wanting a full sleeper, while a cost-conscious owner-operator might prefer to save the cash.

The E8's interior is robust, rather than plush, in keeping with its fleet audience. But the beige and brown interior is by no means unattractive and should be easy to keep clean. The use of slightly tinted glass in the windscreen is a nice touch.

Plenty of room within the rest cab means distribution and long-haul drivers alike have room enough to store their gear. The raised bunk leaves storage space below, and there are plenty of other places for odds and ends.

Driving the E8.21 is simplicity itself. All that power makes it more car-like than any of the regular ERF 17 tonners that have gone before.

The cab interior is quiet, thanks to the company's 'green' exhaust system. Tucked away under the chassis it reduces drive-by and in-cab noise appreciably.

The decision to buy an E8.21 is likely to be based on a need either to cover a lot of motorway miles quickly, or to get round a tortuous hill route fast (or a combination.of both) rather than its economy.

A quick look at our comparison chart shows the E8.21 to be rather unspectacular on payload, although in mitigation our test rigid did have a longer-than-average wheelbase.

It should also be said that the extra 2.37 litres of C-Series engine must be a contributing factor to this, although the engine is not that much heavier than the smaller B-Series alternative after the charge-cooler and its associated trunking have been dispensed with.

Even if you are certain this is the drive train for you, there is an alternative in the form of the Cargo 1721. That currently has a list price of 233,040, which is £365 higher than the ERF.

That, of course is only the point where the haggling really begins.

Equipment levels between these two trucks vary little and are unlikely to enter much into the purchasing decision. As all such trucks become more similar, on price as well as specification, the decision is likely to boil down much more to who has the best dealer.

Efficient service and competent technicians can save more money in a year than the differences between the fuel consumption of any two vehicles.

0 by Danny Coughlan