CURITIEIA OR BUST

Page 36

Page 37

Page 38

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

"Suddenly Jo5o cut our truck's lights, pulled to the offside and accelerated.

'With our lights off we'll see the glow of anything coming down the mountain, he said"

by Brian Cottee I HOPE Curitiba appreciates its ice cream. It would if it knew the effort and risk involved in getting the stuff there. Like almost all the things this Brazilian town eats or uses, the ice cream travels by road, mainly over the mountain and valley highway from the city of Sao Paulo.

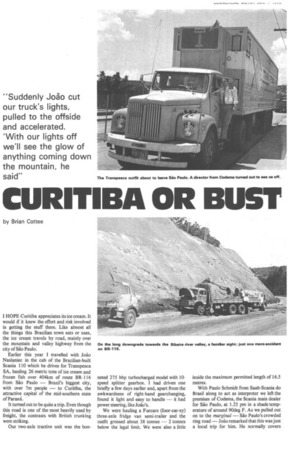

Earlier this year I travelled with Joao Naslaniec in the cab of the Brazilian-built Scania 110 which he drives for Transpesca SA, hauling 26 metric tons of ice cream and frozen fish over 404km of route BR-116 from sao Paulo — Brazil's biggest city, with over 7m people — to Curitiba, the attractive capital of the mid-southern state of Parana.

It turned out to be quite a trip. Even though this road is one of the most heavily used by freight, the contrasts with British trunking were striking.

Our two-axle tractive unit was the bon

neted 275 bhp turbocharged model with 10 speed splitter gearbox. I had driven one briefly a few days earlier and, apart from the awkwardness of right-hand gearchanging, found it light and easy to handle — it had power steering, like Joao's.

We were hauling a Furcare (foor-car-ey) three-axle fridge van semi-trailer and the outfit grossed about 38 tonnes — 2 tonnes below the legal limit. We were also a little inside the maximum permitted length of 16.5 metres.

With Paulo Schmidt from Saab-Scania do Brasil along to act as interpreter we left the premises of Codema, the Scania main dealer for sao Paulo, at 1.25 pm in a shade temperature of around 90deg F. As we pulled out on to the marginal — Sao Paulo's crowded ring road — Joao remarked that this was just a local trip for him. He normally covers

much greater distances on Brazil's main north-south trunk routes, from the Uruguayan border to the ports of Salvador or Recife 2000 miles away on the northeast coast. His most regular run is between Sao Paulo and Rio Grande do Sul, which is a week's round trip.

He confided that he sometimes used to cover as many as 750 miles in a single working stint, with rest and meal breaks — and the Brazilian owner-driver typically works a 14-hour day, since there are no legal limits.

Now Joao goes where the freight takes him. His employer, Transpesca, is a wellrun company with 90 insulated and refrigerated trucks. When Joao arrives with a load, there is a message waiting with details of his next job. Sometimes he is away from his home near Curitiba for a month at a time.

Was he married, I asked? No, but he has a girl in every port. Joao is 33, bronzed and good-looking; he has been driving trucks for 11 years, having been taught by his truck-driving brother.

Out of town

Off the marginal now, passing our first wreck (a burnt-out fuel delivery tanker on a flyover) we bounce at 20 kph through the southern suburbs of this sprawling, dusty city. We are in a grinding mass of trucks and cars trying to dodge the worst potholes. "Some potholes," says Joao; "they're hiding places!"

On our right now is Sao Paulo's vast new fruit and vegetable distribution centre, a growing feature of the Brazilian transport system. Then suddenly we are going smack through the centre of a top-class residential area — like slapping the old Al through the middle of Dulwich.

The sun is blinding on the dusty white tarmacadam. Joao sits relaxed at the highset wheel in tee-shirt, thin slacks and moccasins — no socks, no sunglasses. It is quiet enough in this bonneted model to converse normally even during the occasional bursts of full throttle.

Many Brazilian trucks have sleepercabs but this one does not. Joao sometimes sleeps across the seats but he carries a hammock for the really hot nights and, like many drivers, slings it under the trailer. If his night stop is in a big town he may take a hotel room but he never stays at drivers' pull-ups. "Too many thieves about."

As we clear the city limits of Sao Paulo at 2.05 pm — it has taken us 30 minutes to cover about 11 miles — we pass a roadside stall selling hammocks for drivers.

Clear of the city we travel on an indifferent road — Brazil's only north-south freight trunk route — through rolling green country. Traffic is thinning and Joao can talk more freely. He tells me he works a six-day week, but loading and unloading time — which counts as working time even if he's not actually helping with the loading — often occupies three of the six days. For a 30-day month a Brazilian long-distance driver gets a basic rate of 1500 cruzeiros, about £115. Living costs probably average out around the same as in Britain: local foods are cheap, housing is dear — and so are clothes, but who needs clothes in that climate? For the first of several occasions on di trip I think longingly of the tons of ice creal swinging along behind us, kept from meltin in this fierce heat by a refrigeration motc taking its power from the engine-drive generator.

Two approaching express bus drivers flic their lights at us and wave. It is driver sig language for an obstruction ahead, usefi warning on a winding road barely tw vehicles wide. We have dipped down free Sao Paulo's 250011 altitude but now ax climbing into the Paranapiacaba Mountainu which rise to only about 3000ft, and w are catching up more traffic now. Jai keeps the rev counter at around 2000 rpn well into the 1400/2200 rpm green sectoi He has to snatch at any gap in the or coming traffic to make progress, the roa, being poorly maintained as well as narrol and crowded; but work has already starteA on improving this route.

Now 20km from the start we are at aroun 2500ft again and almost immediately after "check your brakes" sign we are on th downgrade and there are two four-wheeler smashed into the bank on the opposite sid of the road. There are crates and onion everywhere. I am reminded of the fact that th previous day's Sao Paulo paper carried gruesomely illustrated article on the acciden and injury rate on BR-116, which I had foum a bit sobering.

The road opens out now to two lanes it each direction, well surfaced, and we are soot up to 75 kph — only to be baulked by battered old FNM, the locally built Alf Romeo, crawling downhill with a load 01 :rap metal.

"Hey," says Joao. "If he has to go that owly down here, what is he going to do on ie steep bits!"

As we whip out and past he makes a tying noise. "You can always tell the FNM rivers by their burnt legs." (The FNM 'Tine cowling protrudes into the forward)ntro' cab.) It is reassuring to know that we have dualrcuit service brakes, an exhaust brake and trailer brake — whose lever carries an (tension added by our driver, and dominatig the dashboard.

Eighty-five kilometres out of Sao Paulo e are cruising in 5th high gear between lush -een wooded hills and at each clump of roadde trees trucks are standing with bonnets pen to cool while their drivers loll in the lade or sleep.

On a long straight we pass another crashed tick — its bonnet stove in from a collision. We pass several big fridge vans carrying ie message "Argentina-Brazil international eight' as we descend to the valley of the ibeira River, which is banana, tea and offee country settled mainly by Japanese irmers. The road is almost empty now, to le benefit of average speed and fuel connnption, the latter averaging 25 litres/ DOkin (11.3 mpg) on this route with the cania.

In the Juquiii district, 165km from Sao aulo, Joi6 points out an attractive farm wned by the famous Pele.

We also pass one of the permanent roadde posts of the federal traffic police, which re sited at about 100km intervals. The olice put cones out in the road to slow rivers in case they want to check them r licence, documents and vehicle condion; but we are not stopped.

Now nearly half way to Curitiba, we wing into the yard of the Restaurant de uenos Aires where there are tall sun ielters for trucks and cars to stand in the lade.

Joao takes a hammer and walks round ie truck thumping all the tyres. Apparently itisfled, he leads us into the big, spotless ashroom complete with soap and towels lritish roadside cafes please note) for cooling wash.

In the cafe plastic table tops just like ngland — he exchanges greetings and road ews with other drivers, we each down vo tall glasses of iced Ribeira tea at 12p glass, then we are off No sitting down, no ossiping. Ten minutes is all he takes in 00km.

From here to the point where we enter le state of Parana is the worst part of the iurney for both driver and truck, a potoled macadam road with an abrupt 4in. rop to soft earth verges; conditions which elp to explain why power steering is now o popular in Brazil. By 6.10 pm we have covered a total of 250km and there is a tricky dusk light as we climb out of the river valley into the hills. Banana sellers in thatched shelters at the roadside are doing a brisk trade with truck drivers; their tiny houses and plantations are on the slopes far below.

It is a long, slow haul, constantly calling for changes between 2nd high/3rd low and 3rd high/4th low. There is little chance to overtake, and this is where Joao exploits his knowledge of the road, and the turbocharger, to slip cheekily past slower trucks on a steep stretch crowded with freight.

The heavily laden lorry ahead (one seldom sees empty ones, the rates being so low that high utilization is essential) is hardly moving. Hoot, flash, swing out and we are clawing past at 8 kph. As we start to pull back, a VW driver comes from behind, cuts in, missing death by inches as Joao brakes sharply for him, and dashes on up the road.

"Amateur drivers!" says Joao —literally correct as well as exasperated, since car drivers are classed as amateur motoristas, and to drive anything over 1 ton a driver has to pass a separate test for what is termed a professional licence.

Although the sun has nearly gone, the air still shimmers with heat. At the roadside two nearly naked truck drivers are taking a shower under a waterfall.

Now the afternoon storm — later today than usual — arrives with a fficker of lightning and a patter of big drops. Within minutes the dry heat has gone, the temperature falls 20deg F and the rain crashes down. The road becomes a mist of spray. We are 285km out of Sao Paulo and it is just about dark.

Apart from the tiny rear lights of the trucks crawling round the mountain curves ahead the road is now deserted; we have pulled away from the slow bunch. Most truck drivers are licensed to carry a gun, and most carry one, especially if they haul easily disposable loads of consumer goods. Our van is secure against casual pilferage but another driver told me that on some slow mountain roads the thieves jump down from the banks on to the loads in open trucks and throw movable items over the back, to be picked up by their own following truck., The guns — once standard equipment for drivers' mates — also explain the roadside signs reading "Don't damage the road signs"; the mates used to while away the journeys taking potshots.

The drop The contrast with M1 suddenly becomes acute. It is pitch black, except when the lightning turns the mountains an eerie blue; the rain is torrential, the road winding and steep and the edge unmarked.

"It's a sheer drop of 150 metres on your side, if you could see it", says Job. "A coach with 30 passengers went straight over last winter."

Am I looking depressed? He adds encouragingly: "Only three were killed."

I can't see the edge — I don't particularly want to. But I hope he can. "Useful rock", he says, as if interpreting my thoughts. He points to a large boulder just visible in the headlamps. "The road swings sharp left just here, and there's a big drop". It seems the rock is a legendary landmark which has saved many drivers from going over the edge.

Fragmentary From here on my notes get rather fragmentary:— "Flares. Road subsidence. Down to 5 kph, very steep. Mist rising from hot surface now rain has stopped, cannot see road ahead. Cross state border at 7.35 pm, only 100km to Curitiba. More flares, people waving frantically. Artic tanker has jack-knifed but has hit bank and not gone over the edge. Mist has become fog; how does he see where he's going. Some night vision!"

Suddenly Joao cuts our truck's lights, pulls across to the offside and accelerates. It is pitch black. What on earth is he up to?

He explains. He intends to overtake the two vehicles whose rear lights we can see up ahead, but with his own lights on he can't see the glow from any traffic coming down the mountain road. So he drives in the dark for a bit.

Logical — but what if the descending driver is doing the same?

Fortunately we don't discover the answer to that one, and safely overtake.

Shortly after, we stop at a "fiscal post" where all loaded trucks must pull in to have their documents checked and stamped, and a carbon copy removed. Consignment notes resemble detailed invoices, with items priced because there is a direct tax, at source, of 3 per cent on freight revenue, plus taxes on goods in circulation and industrial materials in transit. We are soon cleared.

Coming down the long slopes out of the hills on good roads we chase the mottoes on the tails of the gaily painted vegetable trucks. "Jesus and truck drivers, keep your distance"; "Love without jealousy is like food without salt".

The truck drivers help each other along, flashing "come on" or "stay back"— it's like AS in the Fifties.

A sudden flicker of white in the headlamps. Two teenage girls run out from the roadside and lift their skirts provocatively. Joao drives straight on and they leap back into the roadside blackness.

With increasing traffic and a growing glow in the sky we enter the outskirts of Curitiba — neon garage signs and cafes — and then we are pulling in to the premises of Cortrasa, the Curitiba Scania dealer which, among other things, we learn maintains 700 trucks a month.

Joao pulls back on to BR-116 en route to his night stop. Paulo and I prepare to head for a hotel, wondering if there'll be ice cream on the dinner menu.

It is 9.30 pm. We have covered 404km in 7hr 55min running time, just about 50 kph (31 mph), which I find remarkable in the conditions. But then, a lot of things about road transport in Brazil are remarkable, as I've recorded before.