Where Nationalization Makes Sense

Page 134

Page 139

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

INEQUITABLE licensing and fare systems, and a lack of co-ordination in services, are the main impressions one is left with after a study of public road passenger transport in Singapore today.

Early this year, a commission of inquiry recommended that the island's bus services be nationalized. Because of its political connotations in Britain, such a step might be considered an unpleasant and drastic remedy, but the commission's findings reveal that, in Singapore, the nationalization of public transport is plain common sense.

Strength is given to this view from a number of sources, one of them, unexpectedly, the fountain-head, so to speak, of the present public transport interests, Sir Thomas Strongman, chairman of the Singapore Traction Co., Ltd.

In giving evidence to the commission, Sir Thomas said that "from the public point of view it is unquestionable that one authority should run the whole passenger transport. ... "

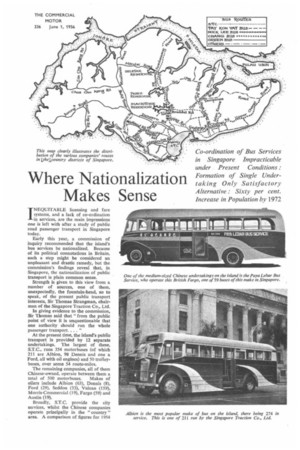

At the present time, the island's public transport is provided by 12 separate undertakings. The largest of these. S.T.C., runs 354 motorbuses (of which 211 are Albion, 98 Dennis and one a Ford, all with oil engines) and 50 trolleybuses, over some 54 route-miles.

The remaining companies, all of them Chinese-owned, operate between them a total of 500 motorbuses. Makes of oilers include Albion (63), Dennis (8), Ford (29), Seddon (33), Vulcan (159), Morris-Commercial (19), Fargo (59) and Austin (19).

Broadly, S.T.C. provide the city services, whilst the Chinese companies operate principally in the " country " area. A comparison of figures for 1954 shows that whilst S.T.C. carried 48 per cent. (85,8m. passengers) of the total traffic and owned 47 per cent. of the vehicles, they worked only 38 per cent. (14.7m. miles) of the mileage.

This inequitable position has been brought about by the two separate systems that exist for the approval and licensing of routes, one applicable to S.T.C. under Section 13 of the Singapore Traction Ordinance of 1925, and the other to all other operators under Section 326 of the Municipal Ordinance.

• Briefly, the Traction Ordinance gives S.T.C. the exclusive privilege of operating trolleybuses. Section 13 authorizes them to run motorbuses on any route, subject to the approval of the City Council and, in their respective areas, the Rural Board.

The Ordinance does not give the council or the board power to attach conditions to licences, nor does it give them control of the density of services. The approval of a service is continuous.

Apart from the general obligation to 'maintain "an efficient service for the public," there are no penalties for " non-compliance."

On the other hand, the Municipal Ordinance requires all other operators to obtain a licence from the City Coun cil or the Rural Board for each service they operate, and authorizes those bodies to attach to the licences any condition they think fit. They also have a say in the frequency of services to be provided.

Subject to Penalties

Under the Municipal (Hackney Carriage) By-Laws of 1950, the Chinese bus companies, but not S.T.C., are subject to penalties for not complying with their licences, or the conditions, and the licences can be suspended if adequate • and satisfactory services arc not maintained.

Their licences, too, are valid for only a year—a period which, in practice, is reduced to six 'months, at the end of which application must be made for renewal.

Section 326 also requires the licensing authority to have regard to the extent to which the needs of the proposed routes are already adequately met by S.T.C.'s services when consideration is being given to applications from other operators.

The result is that a large proportion of the Chinese companies' services run from the country only to points adjacent to the perimeter of the area served by S.T.C., where passengers for destinations in the city have to change to complete their journeys. Even those of the Chinese operators' services that do run into the city normally terminate at a point requiring passengers to change vehicles to reach their objectives.

On some services, passengers have to change three times, each change involving a separate fare, the total of which is often greater than it would be for a through journey over the same distance.

Different fares are charged by S.T.C. and the other operators, in some instances on common stretches of route. S.T.C. charge 10 cents for the first mile and 5 cents for each additional mile, with a maximum of 25 cents. The other companies generally charge a through fare of 5 cents a mile, giving a cheaper ride than S.T.C. for journeys up to four miles, and a more expensive one beyond five miles.

S.T.C.'s fare stages are at roughly half-mile intervals, those of the other companies being a mile apart. A passenger on the S.T.C.'s services thus pays 10 cents for any two successive halfmile stages; he can board a bus at any stage and pay 10 cents for a continuous journey of a mile.

According to the fare-table of the Chinese operators, if a passenger hoards one of their buses at any point between the mile-long stages and travels into the next stage he must pay 10 cents, even though he may travel less than a mile.

The breakdown of bus fleets _given earlier indicated the variety of makes in use on the island. This applies also to the capacity of the vehicles, all of which are single-deckers. The total of 854 buses comprises 58 v?ith 20 or fewer seats, 50 with 21-25 seats, 119 with 26-30 seats, 269 with 31-35 seats, 280 with 36-40 seats, 72 with 41-45 seats, and six with 46-50 seats.

Some degree of standardization, of both makes and types, is obviously desirable. Ideally, there should be one type of vehicle for use on narrow country routes with light loadings, a more comfortable design of bus for express services, and double-deckers for heavy services on main routes and in the city.

Army Carry 10,100 Workers

The island's position as a military base also raises transport problems for both the Services and the bus operators. The Army alone carry 10,100 civilian employees to and from their work every week-day in 510 lorries fitted with loose plank seats and canopies.

Most civilians employed by the Royal Navy travel in 51 privately chartered buses. whilst Royal Air .Force civilian staff generally use the public services, although troop-carrying vehicles are used on routes not served by buses.

Special buses, either privately owned or chartered, are also used for carrying the bulk of the island's school traffic. In 1954, 290 licences were issued for this purpose, although S.T.C. run a number of schoolchildren's " specials" on their regular routes. Obviously, the proper means for transport for this traffic is the scheduled bus.

But these forms of " competition " are not the only contenders for traffic. A more formixlable' enemy is the "pirate" taxi; of which there are some 5,000 (equivalent to one in eight of the private cars registered) in use. These illegal taxis not only pick up passengers along routes, they also take up potential bus passengers waiting at bus stops.

Incidentally, the popularity of the pirate taxi reflects unfavourably on the quality or the bus services. One would expect the bus operators to look for the reasons that made It possible' for an illegal business of these dimensions to be built up. Some, at least, of the causes must be attributable to deficiencies in the existing public services.

The number of licensed taxis in operation is approximately 1,600, and there are also about 4,000 authorized trishas 'on the roads. The trisha, a bicycle with a passenger-carrying sidecar, has succeeded the ricksha arid, as the number of trishas has fallen by 5,000 in the past eight years, it appears likely that these, too, will eventually disappear in favour of the bus and private transport.

It must net be thought that the commission's recommendation to nationalize the public 'services was the outcome of a defeatist attitude on the part of its members, the chairman of which, incidentally, was Mr. L. C. Hawkins, a member of the London Transport Executive.

It is too late to secure co-ordination through the machinery of licensing. because that would seriously disturb the balance and financial stability of remunerative' Mileage 'between the various operators. They could not all. benefit from a replanning of routes on the required scale.

Problem of Co-ordination

Although the willingness of the Chinese operators to'amalgamate into a smaller number of companies would reduce the difficulties of readjustment between themselves, there would still remain the problem of co-ordination between their services and those of the S.T.C. Nor would the present difficulties in securing the provision of unremunerative services be resolved.

In any event, co-ordination would not be practicable without first abolishing or modifying S.T.C.'s special position with regard to licensing matters.

A picture of the future helps to con'firm the wisdom of the recommendation. A recently completed development plan for the island is designed to meet the needs of a population which is expected to rise from approximately 11-m. today to about 2m. in 1972, an increase of 60 per cent. in 16 years.

The plan sets out to limit the amount of travel to and from the centre of the city by restricting the amount of building in the centre and by locating new housing estates and towns outside the city.

Commerce and industry will inevitably rise to satisfy the' demands.of the larger population, and this will 'mean More wrir'rkplaces. New roads are an important part of the scheme, and these will have an effect On MC -layout Of bus routes.

• To meet 'these needs, the public transport policy must be framed on the assumpticin that rapid expansion will be essential. And this would not be possible under present conditions. All these factors lend point to the need for a single flexible transport authority, capable of extending and adapting bus routes to changing conditions, unhampered by individual financial interests.