FORD TRANSIT 30 CM. VAN

Page 68

Page 69

Page 70

Page 73

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

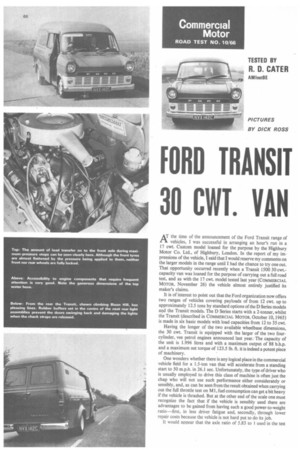

Athe time of the announcement of the Ford Transit range of vehicles, I was successful in arranging an hour's run in a 17 cwt. Custom model loaned for the purpose by the Highbury Motor Co. Ltd., of Highbury. London. In the report of my impressions of the vehicle, I said that I would reserve my comments on the larger models in the range until I had the chance to try one out. That opportunity occurred recently when a Transit 1500 30 cwt.capacity van was loaned for the purpose of carrying out a full road test, and as with the 17 cwt. model tested last year (COMMERCIAL MOTOR, November 26) the vehicle almost entirely justified its maker's claims.

It is of interest to point out that the Ford organization now offers two ranges of vehicles covering payloads of from 12 cwt. up to approximately 12.5 tons by standard options of the D Series models and the Transit models. The D Series starts with a 2-tonner, whilst the Transit (described in COMMERCIAL MOTOR, October 10, 1965) is made in six basic models with load capacities from 12 to 35 cwt.

Having the longer of the two available wheelbase dimensions, the 30 cwt. Transit is equipped with the larger of the two fourcylinder, vee petrol engines announced last year.. The capacity of the unit is 1.996 litres and with a rilaXiI1111n1 output of 88 b.h.p. and a maximum net torque of 123.5 lb. ft. it is indeed a potent piece of machinery.

One wonders whether there is any logical place in the commercial vehicle field for a 1.5-ton van that will accelerate from a standing start to 50 m.p.h. in 26.1 sec. Unfortunately, the type of driver who is usually employed to drive this class of machine is often just the chap who will not use such performance either considerately or sensibly, and, as can be seen from the result obtained when carrying out the full throttle test on Ml, fuel consumption can get a bit heavy if the vehicle is thrashed. But at the other end of the scale one must recognize the fact that if the vehicle is sensibly used there are advantages to be gained from having such a good power-to-weight ratio—first, in less driver fatigue and, secondly, through lower repair costs because the vehicle is not hard put to do its job.

It would appear that the axle ratio of 5.83 to I used in the test cle is better suited to the engine than the 4.444 to 1 ratio I in the 17 cwt. version tested last year. Admittedly the larger ne has a longer stroke by 0.5 in., which would tend to make it • e flexible, but I felt that it was distinctly happier at the lower i speeds than was the 17 cwt. model, despite almost a ton more ;s weight.

he acceleration test also showed that although the available p. per ton was less than on the 17 cwt. model, and despite fact that there are two extra tyres on the road, better figures e achieved both through the• gears and on the direct drive . Full results are shown in the panel on page 71. The maxim speed is probably more likely to show the true picture. The cwt. showed 81 m.p.h. on the clock and the 30 cwt. showed n.p.h.

['here is only the difference in the crankshaft throw and carburetthat distinguishes the 1,700 c.c. engine from its larger brother; package size of the unit remains the same. Because of this the intent made on the 17 cwt.—that the maximum space is left driver and cargo—is even more relevant to this vehicle. Of the of the machine the body is larger, having a load space of 261 ft. plus 21 cu. ft. beside the driver. From the front grille to the r of the first side-panel the two vehicles are, apart from the wheels, Mice. From this point rearwards the side panels are different in longand short-wheelbase versions.

('he underframing follows the same pattern in both cases, the only 'erence being in the length. The exception to this rule is where vehicle is supplied as a chassis/cab or chassis/scuttle, when the lerframing takes on a "cruciform", rather than the ladder-type istruction used in the vans. The construction is from steel pres;s throughout.

[he test area around Barton-in-the-Clay, Bedfordshire, where I :ed the 17 cwt. model, was again used for the 30 cwt. model. As with the smaller vehicle, I collected it from the makers at Toddington, Beds, from where the run to Barton entails traversing about five miles of extremely winding and narrow country lanes. Again I utilized this section to evaluate the general handling qualities of the vehicle before starting the actual test.

Like the previous Transit, I felt immediately at home with it. I held top gear for as long as I could and it was here that I first found the axle ratio to be more suitable. General handling was, as before, first-class, with the steering as near perfect as can be expected.

Although the excellent mirror equipment was specially designed for the Transit range, and when using the wing mirrors one finds them excellent, a slight slip up has been made with the length of the mounting arm on the interior mirror of this machine. The sterndown attitude which the vehicle adopts when laden causes the rear windows to cut off much of the view given by this mirror, and whilst this is acceptable when operating on ordinary roads I found it quite disconcerting when on the motorway through not being able to see far enough behind.

Through careful designing the Ford company has succeeded in obtaining extremely low weight differences at the front axle when laden and unladen. The difference on the test vehicle was only 402 lb. Because of this it is possible to obtain the best possible ride characteristics in both conditions Without having to resort to the use of costly and complicated independent suspensions. The Transit is equipped with leaf-springs and a beam axle, both of which enhance the prospects of long life, and they have a low first cost.

Fuel consumption proved to be very near to another vehicle of the same capacity and also fitted with a petrol engine tested by COMMERCIAL MOTOR. When it is considered that the Ford power unit turns out 44 per cent more power than the engine with which this comparison is made one sees that there has indeed been considerable development with regard to spark ignition petrol units.

The figures obtained showed little difference whether the vehicle was fully or half laden. Big variations in consumption rates became apparent only during the multi-stop tests and in the highspeed tests, especially the latter, as the result obtained at high speed of 11.8 m.p.g. was 56.5 per cent, or almost half of that obtained at 30 m.p.h.-20.8 m.p.g. I would expect to see an overall average consumption of about 16 m.p.g. for the general type of work on which this vehicle is likely to be used.

When testing the last Transit van I was unfortunate to have bad weather. The brake tests were spoiled because of the road

conditions, and the best average retardation readings that could be achieved were 24.4 ft/s2 and 20.8 fils2 from 20 and 30 m.p.h. respectively.

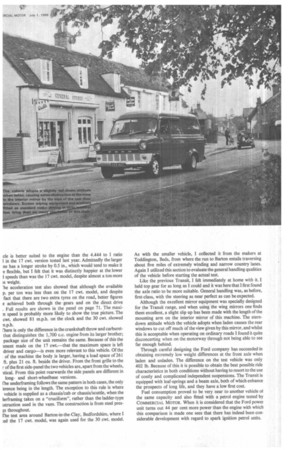

On the day of the current test, the sun shone and road conditions were ideal for brake testing. The first attempt at a recording was spoiled by the front of the van dipping so sharply that all the wires to the brake gun were trapped between the gun and the road and promptly severed.

Reloading the gun, brake tests were resumed and on the first maximum-pressure stop from 20 m.p.h. there was a startling measurement of 12.6 ft. and a reading of 95 per cent on the Tapley meter. As this figure is better than lg. I thought that there must have been a mistake. However, repeats of the test showed the same or better results and with some misgivings I recorded the figures and went on to the 30 m.p.h. tests.

It was not until photographer Dick Ross produced the prints of these tests later that I realized just how efficient the brakes on the 1500 Transit van really are. Again the results were better than lg with the measurements reading 28 ft. and 29 ft. 3 in. Tapley readings recorded were 90 and 98 per cent respectively. The photographic evidence of the stop from 30 m.p.h. which produced the best figure is shown on page 66.

aing all these tests there was no feeling that there would be excitement no matter how hard the vehicle was pushed. much this is because of the twin rear wheels and how much to the perfect balance of braking effort chosen by Ford I do :now. What I am sure of is that the machine can be stopped quickly and safely in almost any conditions.

ie handbrake also produced some good results, showing er cent on the Tapley from 20 m.p.h., and the rear wheels xl solid on each occasion. Receiving such good figures ipted me to check the actual distance that the vehicle :lied before the wheels locked when the footbrake was applied. proved to be 1 ft. 9 in. from 20 m.p.h. and 2 ft. 8 in. from ri.p.h. on the rear wheels and almost instantaneously on the : wheels, a comforting thought for the driver of a machine ble of nearly 80 m.p.h.

am well aware that locked wheels do not give the best braking es, but I doubt if anyone could better the ones recorded on occasion. I must make it clear at this stage that the road • for the brake tests has a very high coefficient of friction and :his particular test was in the very best condition that one d wish for.

he high-speed test was completed on MI between A505 and 7, which is a total distance of 22 miles. The leg north from stable was, as seems inevitable these days, baulked by road works for 2.8 miles and on this run an average speed of 52.8 m.p.h. was recorded. The run south was much better and I was not baulked at all. Letting the machine have its head and clocking for most of the way a steady 70 m.p.h. and slightly over in places an average speed of 66.75 m.p.h. was recorded.

It is in these conditions that the Transit really comes into its own and I can believe that the passenger-carrying versions will make a mark on the small bus and coach market. Fuel consumption gets a bit heavy in these conditions, but I felt that a comfortable 55-60 m.p.h. cruising speed could be made with reasonable economy. Noticeable points on the motorway were that there was no falling off in road speed when on gradual gradients, and that the fairly long rear overhang tended to be caught by the strong blasts of air caused by passing or passed vehicles.

Bison Hill was used for the hill-climb tests and the vehicle put up a really good performance. With an ambient temperature of 15°C (58°F) engine coolant registered a temperature of 81°C (176°F) when checked at the bottom of the hill. A fast run was made up Bison, taking a total time of 1 min. 51.5 sec. to reach the top. Of this time, second gear, which was the lowest used, was engaged for 29.7 sec. The lowest speed recorded was 25 m.p.h. and when the coolant temperature was checked at the end of the climb, a reading of 87°C (186°F) was recorded.

Turning the vehicle round, the usual COMMERCIAL MOTOR brake-fade test was carried out: coasting down Bison against the brakes at approximately 20 m.p.h. and, when the speed fell below 20, engaging top gear and driving the vehicle against the brakes. A total time of 2 min. 32 sec. was taken, of which 46.8 sec. was covered in top gear. When a full-pressure stop was made at the end of the run down, a Tapley meter reading of 83 per cent was recorded, which was 12 per cent lower than that recorded when the brakes were cold.

Returning to the steepest section of the hill, handbrake and stop-and-start tests were carried out. I thought that because the whole distance up had been covered without using bottom gear, I might make a second gear start. This was tried, but unsuccessfully. First-gear starts were easy and the handbrake stopped the vehicle dead when applied whilst rolling down backwards.

There is no doubt that the Lockheed Duo-Servo shoes are a decided advantage here because the effort that has to be applied to the lever is not by any means great. Facing down the hill the results regarding reverse starts and handbrake holding were the same, with both being accomplished easily.