MECHANICAL TENDENCIES FOR 1929.

Page 40

Page 41

Page 42

Page 43

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

An Article Dealing with Recent Technical Advances and What They Augur for the Future.

WTHAT a wonderful year the one just drawn to a close has been ! If one books through only a few numbers of The Commercial Motor issued duriag, the year 1925, the difference in general appearance between the vehicles illustrated then and those of thecurrent. series is at first the most striking feature; but closer inspection of the details of eon struetion for both bodywork and chassis shows even greater divergence. However, this is only what the practical, eiagineer calls "paper talk." Actual proof of the pudding is even more convincing. Take a ride in a three-year-old bus -or coach, and note the difference in comfort, speed mid so on between that and a 1929 model. Then drive the equiva, lent goods vehicles, and compare the ease of control, the general speed proclivities and general manceuvrability with those same qualities as possessed by the modern lorry or van. Astounding is a word hardly 'strong enough adequately to describe the comparison.

We all thought that the 1925 editions of the "mechanical horse" were as near perfection as possible, but now, after three short years—or so it seems—everybody is still on the gut eive for further developments. The curious part of it all is that these, looked-for developments are actually taking place all around. us. .0ne manufacturer brings out what is at that time considered to be the last word in construction and mechanical capability.; shertlyafterwards another maker comes, into line, and then this achievement is surpassed by the effect of other fertile brains, and so we go on, approaching Perfeetion in steady strides but never achieving it. Anyone who does not keep up to date is lost in the present whirl of business life.

Where is all this leading, and who benefits from the Improvements incorporated in-the construction of the various types of commercial vehicle? The answer is everybody, even including the manufacturer. The operator gets better value for his money through obtaining much more reliable vehicles which are capable of a splendid all-round performance, furthermore they -require very little attention. The passenger benefits from the points of view of riding comfort and general refinement of chassis components (silence and smoothness of running, for example), whilst the manufacturer is troubled less with service Work and free rephteement of broken or worn parts because the machines he turns out are so much more reliable and roadworthy than were earlier models.

What -may we expect for the future? Looking a long way ahead, one may suppose -that vehicles will grow in length and width if roads he made of suitable width and straight

Mess to carry them. For the immediate future, however, it does not appear to be practicable seriously to increase the size of the largest goods and passenger machines, largely on account of the restrictions offered by our road system. Detail modification, therefore, is the most probable outlet for improvement, although, with the supercharged engine gradually forcing its way—slowly, admittedly, but nevertheless relentlessly—into the private-ear world, there is always the possibility of some brave maker installing what is, in racing parlance, known as a " hot-stuff " power unit into a chassis intended for fast-touring purposes, and with a comparatively small engine create a new era for commercialyehicle enterprise.

A few words anent the supercharger may not be out of place at this juncture, because it is being realized in the private-car world that such a fitment has its advantages, especially with a six-cyliudered engine. Now many racing cars are designed so that the blower creates a very high pressure, which, in turn, means that an extraordinarily high power output per litre of engine capacity is attained. That is all very well for racing, but if applied to, say, a goods chassis, would produce characteristics in performance which are very undesirable. There is another method, however, whereby the 'cylinders are only slightly supercharged, but which results in an increase of power very ranch greater than might be expected without thorough inVestigation. • The six-cylindered engine is unquestionably coming into almost universal use, at any rate for fast passenger serVices,

but distribution difficulties are almost insurmountable without great complication, consequently the torque figure at low ratee of revolution is comparatively small. With the slightly supercharged engine, however, distribution troubles vanish altogether, and the maximum output—and, indeed, the power developed throughout the whole range—can be increased by something approaching 50 per cent. over the no supercharged engine of the einne capacity and type. The supercharger, too, is nowadays quite silent in operation, so that we may expect to see a big jump forward in performance at a future date, although, a course, it must be quite underetood that we are looking some little distance ahead.

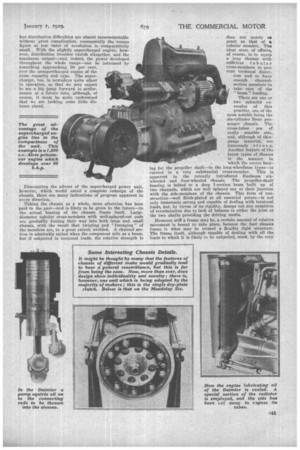

Discounting the advent of the supercharged power unit, however, which would entail a complete redesign of the chassis, there are many indications of progress apparent in every direction.

Taking the chassis as a whole, more attention has been paid in the past—and is likely to be given in the future—to the actual bracing of the chassis frame itself. Largediameter tubular cross-members with well-splayed-out ends are gradually forcing their way into both large and small chassis, with the result that twisting and " lozenging " of the members are, to a great extent, avoided. A channel section is admirably suited when the component acts as a beam, but if subjected to torsional loads, the relative strength is

then not nearly so great as that of •a tubular member. The ideal state of affairs, of course, is to equip a long chassis with sufficient tubular cross-members to prevent torsional distortion and to have enough channelsection members to take care of the " beam " loading.

There are one or two splehilid PAamples of this practice, one of the most notable being the six-cylinder 'Bean paesenger chassis. The cross-tubes are of really sensible size, end, although of thingauge material, are immensely etr on g. Another feature of the latest types of chassis is the manner in which the centre bearing for the propeller shaft—in the long-wheelbase types—is carried in a very substantial cross-member. This is apparent in the recently introduced Sunbeam sixwheeled and four-wheeled chassis. The propeller-shaft bearing is bolted to a deep 1-section beam built up of two channels, which are well splayed out at their junction with the side-members of the chassis. This form of construction—well ilitch-plated at all essential points—is not only immensely strong and capable of dealing with torsional loads, but, by virtue of its rigidity, damps out any suspicion of reverberation due to lack of balance in either the joint or .the two shafts providing the driving media.

However stiff a frame may be, a certain amount of relative movement is bound to take place, because the best chassis

frame is what may be termed a flexibly rigid structure. The frame itself, although capable of dealing with all the loads to which it is likely to be subjected, must, by the very laws of mechanics, flex to a certain extent, for therein lies its strength.

This brings us to the point where we can deal with the mountings of the power -unit and so on. The tendency in all the main units used in the construction of a chassis is to make certain of attaining great rigidity in each component, but to mount them in a flexible manner in the chassis. Take the engine, for instance. Supposing a very rigid crankcase were to be bolted directly to the frame-members, the engine would either act as a restraining influence towards relative movement of the chassis-members, or else it would be insufficiently strong to resist twisting and bending which usually takes place when a vehicle is travelling at high speed over a bumpy road surface. To allow one component to flex and the other to remain rigid, some sort of universal joint has to be used. Preference seems to be given to rubber insulation, especially since the Silentbloc tyne of fitting has become so increasingly popular. The Silentbloe bracket can deal almost equally satisfactorily with movement in any direction—an ideal state of affairs. Eurthermare, it requires no attention and is quite silent in operation —characteristics which gladden the heart

of any big user. The gearbox, too, is often similarly mounted, one advantage of this form of construction being that noise from the gears is, to a certain extent, damped by the rubber packints For spring ' shackles the Silentbloc fitting does not seem to have made the rapid strides which might have been expected. On the other hand, this type of bearing. may well form the subject for serious consideration for the future by virtue of the fact that it requires no attention over long periods of use.

This brings us to another point—the question of central chassis lubrication. In the old days we used to go around the chassis with a tin of grease and an old table knife or broken hacksaw blade and laboriously fill from 20 to 50 brass grease cups. Admittedly, this operation was carried out very infrequently, and even then under protest ; but to do the job properly several hours bad to be set aside before it could be said that all points of the chassis were properly lubricated. The grease-gun altered all that ; the hours spent on lubrication when using the old methods were reduced to minutes with the new method. But the stress of modern times, the longer distances covered in a day, and the general high-pressure service which everybody expects of the modern vehicle made some of us grumble until we got the one-shot chassis-lubrication system.

Most of these systems work quite satisfactorily, but the chassis is complicated somewhat by a whole host of pipes leading to innumerable bearings. Probably the next step will be towards the unification of the details requiring oil at more or less frequent intervals. The brake gear, for instance, will probably be self oiling by making its cross-shafts hollow and of moderately larg,e capacity, so that they can be filled with oil, lubrieation being provided by leak boles to all the necessary points.. Again, there does not seem to he any reason why universal joints on the transmission line could not be oiled from either the ,gearbox or the rear axle. There are ways and means of leading the lubricant up to the right quarter and so keeping the bearing surfaces of the joints themselves adequately supplied. The lubrication of the engine and clutch is, of course, an entirely separate matter and will be dealt with later.

The chief difficulty, of course, in chassis lubrication arises when one attempts to unify the front-axle oiling system. Even there, however, the one-shot system has been applied, so that it is safe to assume that we shall see some simple arrangement whereby all the numerous hearings can be supplied with oilwith a minimum of trouble.

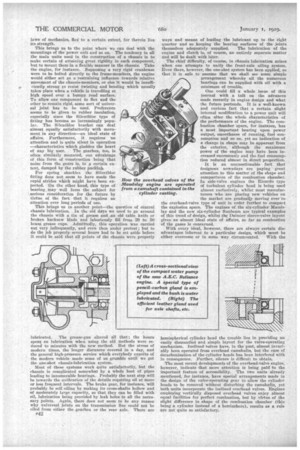

One could till a whole issue of this journal with a talk on the advances made recently in engine design and what the future portends. It is a well-known and curious fact that a certain slight internal modifieation to a power unit will often alter the whole characteristics of the performance of the engine. The combustion chamber space, for instance, has a most .important bearing upon power output, smoothness of running, fuel congumption and so on, yet no indication of a change in shape may be apparent from the exterior, although the maximum power of the engine may have been increased enormtrasly and the fuel consumption reduced almost in direct proportion.

It is an unquestionable fact that designees nowadays are paying great attention to this matter of the shape and compactness of the combustion chamber. In side-valve engines the Ricardo type of turbulent cylinder head is being used almost exclusively, whilst most manufacturers who are placing new vehicles on the market are gradually moving over to the overhead-valve type of unit in order further to compact the explosion space. The engines of the six-cylinder Maudslay and the new six-cylinder Sunbeam are typical examples of this trend of design, whilst the Daimler sleeve-valve layout gives an almost ideal state of affairs, so far as combustion of the gases is concerned.

With every ideal, however, there are always certain disadvantages inherent to a particular design, which must be either overcome or in some way circumvented. With the hemispherical cylinder head the trouble lies in providing an easily dismantled and simple layout for the valve-operating mechanism. Inclined valves have, in the past, almost invariably been operated from overhead camshafts, bat the ease of decarbonization of the cylinder heads has been interfered with in consequence. Further, silence is difficult to obtain.

The most recent developments of the overhead-valve engine, however, indicate that more attention is being pals] to the important feature of accessibility. The two units already mentioned, for instance, have special arrangements made in the design of the valve-operating gear to allow the cylinder beads to be removed without disturbing the camshafts, yet both units incorporate the inclined overhead valves. Engines employing vertically disposed overhead valves enjoy almost equal facilities for perfect combustion, but by virtue of the slight difference in shape of the combustion chamber (this being a cylinder instead of a hemisphere), results as a rule are not quite so satisfactory. More and more attention has been given to lubrication and, In the opinion of the writer, the lasting qualities of the various components subjected to friction has been increased enormously. At long last it has been realized that foreign matter—dust, etc.—in the oil is a wonderful abrasive, and its exclusion by fitting air filters to the carburetter, several large, fine filters in the oil line and possibly one of the proprietary brands of oil cleaner, has marked a very great step in the right direction. Operators nowadays are keen to notice provision for keeping the oil pure, and manufacturers who have not given proper attention to this point will have to come into line during 1929. •

The Importance of Cooling the Oil.

There is another aspect of the lubrication problem—that of oil temperature. Now it is a well-known fact that as the viscosity of oil decreases, so (other things being equal) does the lubricating quality also became less. Further, as viscosity and temperature are connected, it is obviously sound policy to keep the oil as cool as possible.

Oil coolers must come and at least one really successful effort has already been made. We refer, of course, to the new Daimler 35-100 h.p. coach chassis in which the oil is circulated through a section of the radiator. Claims are made that the working temperature of the oil has been decreased from 190° Fahr. to 120° Fahr., which, in turn, means that the cooler oil possesses five times the lubricating qualities of the hotter. Now this is a very big achievement and indicates that under existing conditions g thinner oil can be used satisfactorily.

At first sight this statement appears to be a little wide of the mark, but reflection will show that ills not quite so absurd as it sounds. When the engine is stone cold and is started up, the normal thick oil is delivered under pressure to the main bearings of the crankshaft and the big-end bearings of the connecting rods. The extremely thick nature of the oil, however, does not for a time permit an adequate flow of lubricant through the bearings, so that not only are these journals starved to a certain extent, but there is no oil being flung on to the cylinders and pistons; thus the engine must run several minutes before any adequate " splash " is attained. A thin oil, however, escapes very much more freely and all the internal parts of the engine benefit accordingly.

Stiffening to Reduce Engine Vibration.

Mechanical tendencies point all in one direction—greater and greater rigidity to permit higher and higher revolution speeds. Although the cylinders and crankcase are, in the • larger types of engine, formed in separate units, the internal ribbing for the crankcase and the general stiffness of the cylinder block are well worthy of comment, whilst the crankshaft of larger diameter and with thicker webs is now a very much sturdier component than in the past. Even so, there are still some engines which suffer from crankshaft torsional vibration at critical speeds (usually around the maximum torque). The vibration is most unpleasant and in the present state of development is a thing not to be tolerated.

The question of the pros and CODS, of the four, six or eight-cylindered engine is too big altogether for a comprehensive article such as this, and will be dealt with separately in an early issue of The Commercial Motor. Each type has its own claims to suitability for certain classes of work. It must he noted, however, that there is a growing tendency towards an increase in the number of "sixes," especially among the fast passenger types of chassis. It is doubtful whether the straight-eight engine will ever be developed to any great extent for use in a commercial vehicle on account of the length of the engine, although it is used in the Miesse six-wheeler, but there is no doubt that the " six " will continue to be used in increasing numbers. There is just the possibility that, on account of space, the horizontally oppoSed " eight " (with four cylinders astride a common crankshaft), may be developed because of its compactness, but it is thought that such a development is unlikely to take place during 1929.

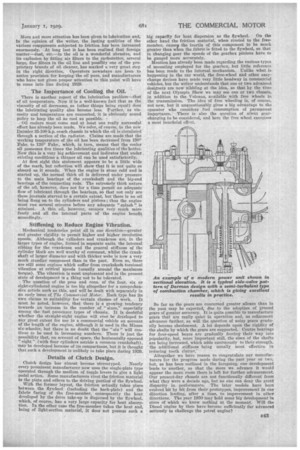

Details of Clutch Design.

Clutch design has almost become stereotyped. Nearly every prominent manufacturer now uses the single-plate type operated through the medium of toggle levers to give a light pedal action. Some manufacturers rivet the friction material to the plate and others to the driving portion of the flywheel. With the former layout, the friction actually takes place between the flywheel (including the hack-plate) and the fabric facing of the free-member, consequently the heat developed by the drive take-up is dispersed by the flywheel, which, of course, has a very large capacity for heat absorption. In the other case the free-member takes the heat and, being of light-section material, it does not possess such a

big capacity for heat dispersion as the flywheel. On the other hand the friction material, when riveted to the free. member, cause the inertia of this component to be much greater than when the fabric is fitted to the flywheel, so that in changing gear the speeds of the gearbox pinions have to be gauged more accurately.

Mention has already been made regarding the various types of mounting employed for the gearbox, but little reference has been made to the internal mechanism. Unlike what is happening in the car world, the free-wheel and other easychange devices have made very little headway in commercial vehicles, but the writer understands that one or two advanced designers are now nibbling at the idea, so that by the time of the next Olympia Show we may see one or two chassis, in addition to the Vuleans, available with free wheels in the transmission. The idea of free wheeling is, of course, not new, but it unquestionably gives a big advantage to the operator who considers fuel consumption of paramount importance." There is also the question of silent gearchanging to be considered, and here the free wheel exercises a most beneficial effect.

So far as the gears are concerned greater silence than in the past may be expected, due to the adoption of ground gears of greater accuracy. It is quite possible to manufacture gears that are really quiet in operation and, as refinement advances farther, so will the question of noisy gears gradually become obsolescent. A lot depends upon the rigidity of the shafts by which the gears are supported. Centre bearings for four-speed boxes are gradually forcing their way into popularity, but, more important still, the sizes of the shafts are being increased, which adds enormously to their strength, ' the additional stiffness being usually most effective in reducing tooth clatter. Altogether we have reason to congratulate our manufacturers for the progress made during the past year or two, but, as has been outlined in the foregoing, one development leads to another, so that the more we advance it would appear the more room there is left for further advancement. Our present-day .chassis are not functionally different from what they were a decade ago, but no one can deny the great disparity in performance. The later models have been evolved bit by bit from their prototypes, improvement in one direction leading, after a time, to improvement in other directions. The year 1930 may hold some big development in store of which we know nothing at the moment. Will the Diesel engine by then have become sufficiently far advanced seriously to challenge the petrol engine?