HOW SIX CYL

Page 24

Page 25

Page 26

Page 27

Page 28

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

1ERS and LS make

SIX WI

for REF

;MENT.

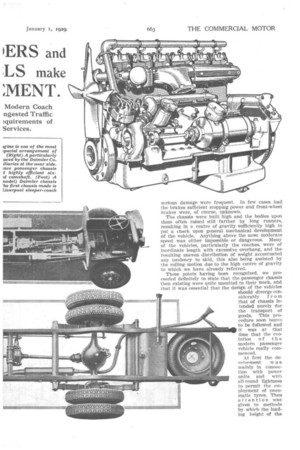

IT is not so very long ago that practically the only difference between a chassis designed for the transport of goods and one intended for equipping as a passenger vehicle—either bus or coach— lay in the suspension. Often the difference, so far as the passenger-carrying chassis went, was merely a question of a reduction in the number of leaves employed in the springs. Sometimes, however, the two kinds of chassis were merged into one—in other words they became identical. In a few instances chassis makers went a step beyond spring modification and provided different ratios for the final drive, but this was considered to be almost a luxury, The Commercial Motor was the first journal fully to appreciate the potentialities of passenger transport by road and to foresee the way in which it was likely to grow, and we were quite convinced that the types of chassis then existing, although bridging a gap, did not in any way aPproach the ideal. Their engines were unsuited to long periods of fast running, even when they were capable

of any considerable speed at all; not only were they

too clumsy but, in some instances, the methods of lubrication were totally inodequate. a a d • even at the most modest speeds then prevailing, 12a SeS of seizing up or other

serious damage were frequent. In few cases had the brakes sufficient stopping power and front-wheel brakes were, of course, unknown.

The chassis were built high and the bodies upon them often raised still farther by long runners, resulting in a centre of gravity sufficiently high to put a check upon general mechanical development of the vehicle. Anything above the most moderate speed was either impossible or dangerous. Many of the vehicles, particularly the coaches, were of inordinate length with excessive overhang, and the resulting uneven distribution of weight accentuated any tendency to skid, this also being assisted by the rolling motion due to the high centre of gravity to which we have already referred.

These points having been recognized, we proceeded definitely to state that the passenger chassis then existing were quite unsuited to their work, and that it was essential that the design of the vehicles should diverge considerably from that of chassis intended purely for the transport of goods. This procedure soon begon to be followed and it was at that time that the evolution of the modern passenger vehicle really commenced.

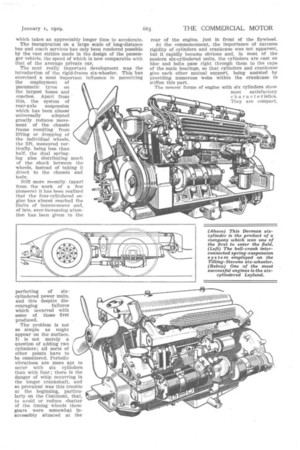

At first the develonment was mainly in connection with power units and with all-round lightness to permit the employment of pneumatic tyres. Then attention was given to methods by which the loading height of the

body and the centre of gravity of the complete vehicle could be reduced, and, for this purpose, chassis with low frames arched over the rear axles practically swept the board. At first, there were certain disadvantages, mainly in respect of accessibility, for it was not immediately realized that, without a pit, it was practically impossible for a mechanic to get under the vehicle ; later, however, designs were so modified as to permit access from above through trapdoors in the floor, so that the major units could be either lifted out or dropped without employing a pit.

Traffic conditions which have pertained during the past few years have exercised a considerable influence upon bus and coach design. It has been realized, even by the authorities, that the slow vehicle is one of the factors in traffic congestion. It impedes the normal flow and, by forcing faster vehicles continually to pass it adds to the existing dangers, and from what we know ourselves about driving and from what others have told us, we believe that the average user of the road would rather be passed by an occasional coach than to be forced continually to pass them. worst Again, in traffic, rapid acceleration is a factor of the utmost importance. It is the vehicle which can get away quickly, where long runs are not possible, that reaches its destination first, although its maximum speed may not be so great as that of another type which takes an appreciably longer time to accelerate.

The inauguration on a large scale of long-distance bus and coach services has only been rendered possible by the vast strides made in the design of the passenger vehicle, the speed of which is now comparable with that of the average private car.

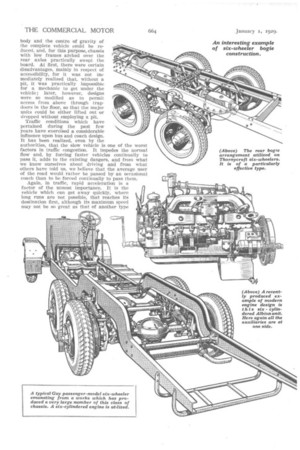

The next really important development was the introduction of the rigid-frame six-wheeler. This has exercised a most important influence in permitting the employment of pneumatic tyres on the largest buses and coaches. Apart from this, the system of rear-axle suspension which has been almost universally adopted greatly reduces movement of the chassis frame resulting from lifting or dropping of the individual wheels, the lift, measured vertically. being less than half, the dual springing also distributing much of the shock between the wheels, instead of taking it direct to the chassis and hefty.

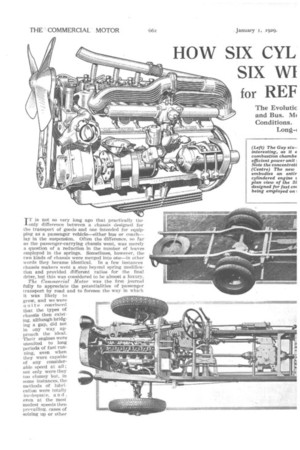

Still more recently (apart from the work of a few pioneers) it has been realized that the fonr-eylindered engine has almost reached the limits of improvement and, of late, ever-increasing attention has been given to the perfecting of sixcylindered power units, and this despite dis couraging failures which occurred with some of those first produced.

The problem is not so simple as might appear on the surface. It is not merely a question of adding two cylinders; all sorts of other points have to be considered. Periodic vibrations are more apt to occur with six cylinders than with four ; there is the danger of whip occurring in the longer crankshaft, and so prevalent was this trouble at the beginning, particularly on the Continent, that, to avoid or reduce chatter of the timing wheels these gears were somewhat inaccessibly situated at the rear of the engine, just in front of the flywheel.

At the commencement, the Importance of extreme rigidity of cylinders and crankcase was not apparent, but it rapidly became obvious and, in most of the modern six-cylindered units, the cylinders are cast en bloc and bolts pass right through them to the caps of the main bearings, so that cylinders and crankcase give each other mutual support, being assisted by providing numerous webs within the crankcase to stiffen this part.

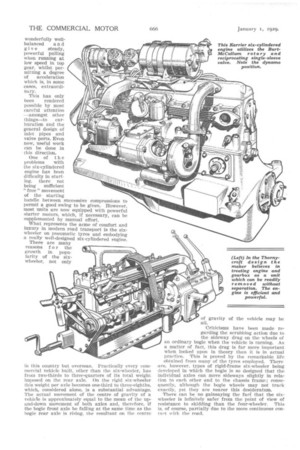

The newest forms of engine with six cylinders show most satisfactory characteristics. They are compact, wonderfully well balanced and give steady, powerful pulling when running at low speed in top gear, whilst permitting a degree of acceleration which is, in some cases, extraordinary.

This has only been rendered possible by most careful attention —amongst other things—to carburation and the general design of inlet pipes and valve ports. Even now, useful work can be done in

• this direction. One of the problems with the six-cylindered engine has been difficulty in starting, there not being sufficient "free" movement of the starting handle between successive compressions to permit a good swing to be given. However, most units are now equipped with powerful starter motors, which, if necessary, can be supplemented by manual effort.

What represents the acme of comfort and luxury in modern road transport is the sixwheeler on pneumatic tyres and embodying a really well-designed six-cylindered engine. There are many reasons f o r the growth in popularity of the sixwheeler, not only in this country but overseas. Practically every commercial vehicle built, other than the six-wheeler, has from two-thirds to three-quarters of its total weight imposed on the rear axle. On the rigid six-wheeler this weight per axle becomes one-third to three-eighths, which, considered alone, is a substantial advantage. The actual movement of the centre of gravity of a vehicle is approximately equal to the mean of the upand-down movement of both axles and, therefore, if the bogie front axle be falling at the same time as the bogie rear axle is rising, the resultant on the centre of gravity of the vehicle may be nil.

criticisms have been made regarding the scrubbing action due to the sideway drag on the wheels of an ordinary bogie when the vehicle is turning. As a matter of fact, this drag is far more important when looked upon in theory than it is in actual practice. This is proved by the remarkable life obtained from many of the tyres employed. There are, however, types of rigid-frame six-wheeler being developed in which the bogie is so designed that the individual axles can move sideways slightly in relation to each other and to the chassis frame; consequently, although the bogie wheels may not track exactly, yet they are nearer this desideratum.

There can be no gainsaying the fact that the sixwheeler is infinitely safer from the point of view of resistance to skidding than the four-wheeler. This is, of course, partially due to the more continuous contact with the road.