ON THE OLYMPIC RUN

Page 72

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Now the dust has settled on the Luton-built Bedford Midi Turbo van's Herculean the UK to Olympia in Greece, we assess how the vehicle has coped • The joint Bedford/Commercial Motor expedition to Greece earlier this year presented us with the opportunity for some sustained foreign testing of the new Japanese-designed, Luton-built, Turbodiesel Midi.

Our vehicle, a short-wheelbased model, is equipped with the blown diesel engine launched in the Midi in April this year. It is available in all the Midi derivatives except the long-wheelbased panel van, which is not made by Isuzu in Japan. Bedford could not justify a special design for that vehicle without looking at the likely sales volumes first. We expect that an LWB panel van turbo-diesel should be launched some time next year.

The two-litre engine delivers 51kW (68hp) DIN at 4,000rpm, and 167Nm (1,2311bft) DIN at 2,300rpm, with a 21.3:1 compression ratio. There is a fivespeed all-synchromesh gearbox, with a floor-mounted gear lever. Isuzu builds the engines and gearboxes for the vehicle, and IBC fits them into the in-house-built bodies.

The unit's performance is surprisingly good between 48-112krn/h: the compressor really bites in fourth gear, and the partly-laden van punches forward rapidly once the 2,900rpm point is reached. Although the power delivery is progressive, it falls off rapidly below 2,900rpm. There is also a sizeable lag to the throttle response during which the driver can entertain himself with a few bars of music, or can roll a cigarette.

The engine is a raucous performer, shouting its head off at engine speeds above 3,500rpm. Vibration is low from the unit, although it makes its presence felt with the heat, which enters the cab through the floor and engine cover.

The gearbox ratios allow 1291cm/h (80mph) cruising, although there is quite a gap between third and fourth, which means holding on to third gear like a UK parcels van driver, just to make normal progress. Third gear is also hard to find when the gearlever spring-loading is doing its best to create a box full of neutrals. The van's impressive acceleration through first and second gears just about makes up for the time spent finding third when in a hurry, by which time the following traffic has caught up.

On the run down to Olympia, the van achieved an impressive fuel consumption of 8.42 litres/100km (33.56mph) at an average speed of 82.8km/h (51.5mph). This was over some of the worst roads in Europe, with high-speed German autobahn driving, and a hair-raising passage over the single-carriageway A roads in Yugoslavia, where overtaking is not so much a way of life, but a sneak preview of eternal damnation.

Forward-control vans always seem to give the impression of massive understeer, although in the Midi's case, with virtually no load in the rear, and two large adults in the front, the front wheels have a lot to do. Understeer, however, is not such a good idea on fast corners, where crumbling road edges and diesel-soaked road surfaces conspire to try to hurl the Midi into the picturesque village some 500m below.

OPTIMUM SUSPENSION

The suspension was near its optimum condition in our experience. Most Japanese-designed vans are at their worst in the fully-laden or unladen condition. Even Yugoslavia's best could not bottom the front suspension, although fast cornering could leave the passenger clawing for the door handle if the surface deteriorated through the corner.

Driven correctly, on fair surfaces, the part-laden Midi corners with a fair degree of predictability. Bad surfaces, overgenerous velocities, or possibly a full load, upset the equation, and the resulting sum can be uncomfortable.

The interior of the Midi is typical of Japanese design, except the Midi's doors don't flap open at speed. Grey plastic abounds, and the fascia informs the driver on the speed (engine and road), water temperature, and fuel load.

There is also a stupendously annoying green light that appears when the turbocharger is producing useable boost. The gearlever is a little too far away to keep shoulder muscles relaxed, but the shift pattern is logical, except for the previously mentioned confusing spring loading.

Apart from the gearlever stretch, the rest of the driving position is very comfortable, with light, if a little vague steering and — the biggest surprise of all — very comfortable seats.

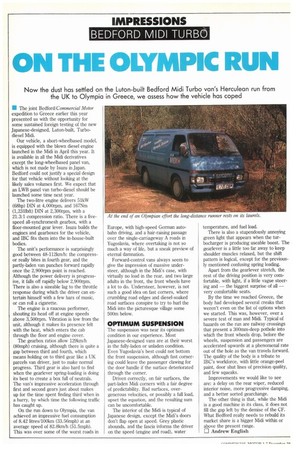

By the time we reached Greece, the body had developed several creaks that weren't even on the list of options when we started. This was, however, over a severe test of man and Midi. Typical of hazards on the run are railway crossings that present a 300mm-deep pothole into which the front wheels drop, before the wheels, suspension and passengers are accelerated upwards at a phenomenal rate out of the hole as the van travels forward. The quality of the body is a tribute to IBC's workforce, with tittle orange-peel paint, door shut lines of precision quality, and few squeaks.

Improvements we would like to see are: a delay on the rear wiper, reduced interior noise, more progressive damping, and a better sorted gearchange.

The other thing is that, while the Midi is a good machine in its class, it does not fill the gap left by the demise of the CF. What Bedford really needs to rebuild its market share is a bigger Midi within or above the present range.

LI Andrew English