Unlucky 13

Page 23

Page 24

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

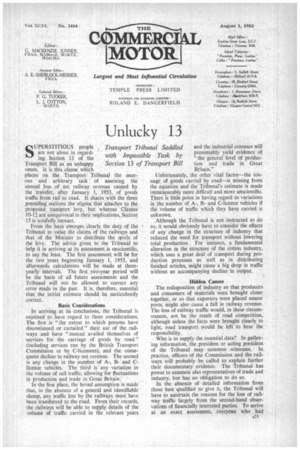

Transport Tribunal Saddled with Impossible Task by Section 13 of Transport Bill SUPERST1TIOUS people are not alone in regarding Section 13 of the Transport Bill as an unhappy omen. It is this clause' which places on the Transport, Tribunal the onerous and arbitrary task of assessing the annual loss of net railway revenue caused by the transfer, after January 1, 1953, of 'goods traffic from rail to road. It shares with the three preceding sections the stigma that attaches to the proposed transport levy, but whereas Clauses 10-12 are unequivocal in their implications, Section 13 is woefully inexact.

From the haze emerges clearly the duty of the Tribunal to value the claims of the railways and that of the Minister to distribute the spoils of the levy. The advice given to the Tribunal to help it in arriving at its assessment.is unscientific, to say the least. The first assessment, will be for the two years beginning January I, 1953, and afterwards calculations will be made at threeyearly intervals. The first two-year period will be the basis of all future assessments and the Tribunal will not be allowed to correct any error made in the past. It is, therefore, essential that the initial estimate should be meticulously correct.

Basic Considerations In arriving at its conclusions, the Tribunal is enjoined to have regard to three considerations. The first is "the extent to which persons have discontinued or curtailed" their use of the railways and have "instead availed themselves of services for the carriage of goods by road" (including services run by the British Transport Commission or by C-licensees), and the consequent decline in railway net revenue. The second is any change in the number of A-, Band Clicence vehicles. The third is any variation in the volume of rail traffic, allowing for fluctuations in production and trade in Great Britain.

In the first place, the broad assumption is made that, in the absence of a general and identifiable slump, any traffic lost by the railways must have been transferred to the road. From their records, the railways will be able to supply details of the volume of traffic carried in the relevant years and the industrial censuses will presumably yield evidence of "the general level of production and trade in Great Britain."

Unfortunately, the other vital factor—the tonnage of goods carried by road—is missing from the equation and the Tribunal's estimate is made immeasurably more difficult and more unscientific. There is little point in having regard to variations in the number of A-, Band C-licence vehicles if the volume of traffic which they have carried is unknown.

Although the Tribunal is not instructed to do so, it would obviously have to consider the effects of any change in the structure of industry that reduced the need for transport without lowering total production. For instance, a fundamental alteration in the structure of the cotton industry, which uses a great deal of transport during production processes as well as in distributing finished articles, might cause a big drop in traffic without an accompanying decline in output.

Hidden Causes The redisposition of industry so that producers and consumers of materials were brought closer together, or so that exporters were placed nearer ports, might also cause a fall in railway revenue. The loss of railway traffic would, in these circumstances, not be the result of road competition, although unless the facts were brought clearly to light, road transport would be left to bear the responsibility.

Who is to supply the essential data? In gathering information, the president or acting president of the Tribunal may summon witnesses. In. practice, officers of the Commission and the railways will probably be called to explain further their documentary evidence. The Tribunal has power to summon also representatives of trade and industry, but has no obligation to do so. In the absence of detailed information from those best qualified to give it, the Tribunal will have to ascertain the reasons for the loss of railway traffic largely from the second-hand observations of financially interested parties. To arrive at an exact assessment, everyone who had curtailed or discontinued his use of the railways would have to be questioned. In addition to these difficulties, theLe is the obligation of making allowance for any loss of net railway revenue which the Commission could have avoided by reasonable economies in consequence of the reduced use of its services. Who is to say what the effect on the whole railway undertaking of any particular economy might been?

For instance, it might be argued that with less net revenue, the railways should reduce their advertising. On the other hand, it can be contended with equal truth that when .business is declining, that is the time to increase advertising expendi Lure. No one can predict with certainty the ultimate outcome of adopting either of these courses, but any action that failed to produce a favourable result would lay the railways open to a charge of having neglected their duty. The whole of Section 13 is riddled with inconclusiveness and impracticability. It is a worthy foundation on which to erect an arbitrary and unjust transport levy, it has been suggested that a result a& accurate as any which the Tribunal might achieve under the procedure envisaged in Section 13, could be reached by choosing a night of full moon, boiling a frog's entrails in raven's blood and consulting the conjunction of the planets. The Tribunal could do worse.