BRAIN POW

Page 40

Page 41

Page 42

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Cummins says ESP is the first big-bore diesel that thinks for itself—it certainly has a number of features that set it apart it from the multi-rated engines developed by Caterpillar and Detroit Diesel (CM 11-17 March). Mack, North America's only other heavy duty engine manufacturer, has yet to enter the race.

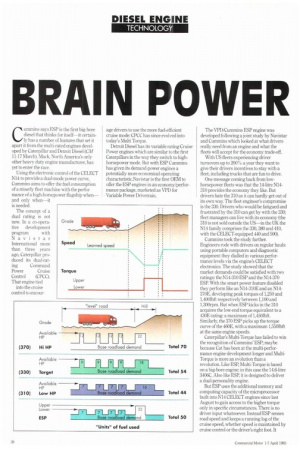

Using the electronic control of the CELECT N14 to provide a dual-mode power curve, Cummins aims to offer the fuel consumption of a miserly fleet machine with the perfor mance of a high-horsepower flagship when— and only when—it is needed.

The concept of a dual rating is not new. In a co-operative development program with Navistar International more than three years ago, Caterpillar produced its dual-rat ing Command Power Cruise Control (CPCC).

That engine tied into the cruise control to encour age drivers to use the more fuel-efficient cruise mode: CPCC has since evolved into today's Multi Torque.

Detroit Diesel has its variable rating Cruise Power engines which are similar to the first Caterpillars in the way they switch to high. horsepower mode. But with ESP Cummins has given its demand-power engines a potentially more economical operating characteristic.Navistar is the first OEM to offer the ESP engines in an economy/performance package, marketed as VPD for Variable Power Drivetrain. The VPD/Cummins ESP engine was developed following a joint study by Navistar and Cummins which looked at what drivers really need from an engine and what the fleets will accept for the economy trade-off.

With US fleets experiencing driver turnovers up to 200% a year they want to give their drivers incentives to stay with a fleet, including trucks that are fun to drive.

One message coming back from lowhorsepower fleets was that the 14-litre N14310 provides the economy they like. But drivers hate the 310 as it can hardly get out of its own way. The fleet engineer's compromise is the 330. Drivers who would be fatigued and frustrated by the 310 can get by with the 330; fleet managers can live with its economy (the 310 is not sold outside the US—in the UK the N14 family comprises the 330.380 and 410, with the CELECT-equipped 440 and 500).

Cummins took the study further. Engineers rode with drivers on regular hauls: using portable computers and diagnostic equipment they dialled in various performance levels via the engine's CELECT electronics. The study showed that the market demands could be satisfied with two ratings: the N14-310 ESP and the N14-370 ESP. With the smart power feature disabled they perform like an N14-310E and an N14370E, developing peak torques of 1,250 and 1,400Ibft respectively between 1,103 and 1,300rpm. But when FSP kicks in the 310 acquires the low-end torque equivalent to a 4.30E rating: a maximum of 1,4501bft. Similarly, the 370 FSP picks up the torque curve of the 460E, with a maximum 1,5501bft at the same engine speeds.

Caterpillar's Multi-Torque has failed to win the recognition of Cummins' ESP; maybe because Cat has been at the multi-performance engine development longer and MultiTorque is more an evolution than a revolution. Like ESP, Multi-Torque is based on a big-bore engine: in this case the 14.6-litre 3406C. Also like ESP, it is designed to deliver a dual-personality engine.

But ESP uses the additional memory and computing capacity of the microprocessor built into N14 CELECT engines since last August to gain access to the higher torque only in specific circumstances. There is no driver input whatsoever. Instead ESP senses road speed and keeps a running log of the cruise speed, whether speed is maintained by cruise control or the driver's right foot. It looks for the condition of a falling road speed even when the driver has the pedal to the metal: this tells the computer that the truck is demanding more horsepower than the engine can produce at its nominal rating.

As the computer already knew the engine was making enough power for the flat road cruise mode, it knows that this additional demand is in response to hill-climbing so it kicks in the high-torque mode. When the hilIclimb is completed ESP automatically drops back to the lower performance curve.

Caterpillar makes use of the electronic processing power in its electronic fuel control module to compare engine revs with road speed to determine the changeover point to high-torque mode. Unlike ESP Multi-Thrque will only drop back to economy mode when the driver eases off the pedal so in theory the truck will accelerate beyond the desired cruise speed. But at the top end of the rev range high and low torque power ratings converge, so if the truck is limited by available power to a certain top speed that all you'll get.

Detroit Diesel's Cruise Power is so named because the enabling switch is the cruise control built in to the Detroit Diesel Electronic Control (DDEC) module. The variable speed governor responds to a slowing engine by passing fullload fuel to the engine until it returns to speed. With the limiting speed governor the fuel system only applies fuel in proportion to the position of the pedal.

Using this feature an experienced driver can improve fuel consumption by juggling the throttle and the boost gauge to save fuel on hillelimbs on grades, then use downward runs to shoot the next hill.

But for a less skilled driver, or a driver who is getting tired, the fine difference between the two modes will tip in favor of the cruise control. Cummins predicts that the 310 ESP will reduce gearshiffing by 75°u while maintaining road speed. The engine will not give the same economy as the 310 but it does combine the fuel economy of a 33 with the hill-climbing ability of a 430E. It all sounds impressive enough; CM has driven a Cummins ESP-equipped WhiteGMC and a Cat Multi-Torque powered Kenworth to compare theory with reality..

IMPRESSIONS

Cummins and Caterpillar are both based in the flatlands of the Mid West so we were pressed to find hills that would show how the ESP 310 and 370 function from the driver's seat.

For the Cummins test we headed south to find a 30-mile loop in Northern Kentucky where there WRS a long-enough. steep-enough grade to get the ESP feature to engage.

We were able to run both ratings on the same day in the same truck—a WhiteGMC WIA64 with 13-speed and 3.70:1 rear end— because the performance was simply downloaded from the suitcase-sized Compulink computer tool. We were loaded to around 34 tonnes.

The first run was with a 310 E rating, with ESP turned off, to give us a base-line for the gradeability and the fuel consumption. Fuel use was measured using the optional RoadRelay performance gauge/computer monitor mounted on the dash.

In this mode there was no question of handling the 3 °. test slope in top gear. Even entering the hill at 60mph and downshifting quickly at around 1.200 rpm we were lucky to stagger over the top at :39 mph in 8th direct. It took 3min 45sec between the mile markers used to time the climb.

Repeating the run with ESP engaged, once again with a 60mph starting speed, we had 100 only lost 4mph before noting a rise inturhocharger speed. The boost jumped up by 5psi and we sailed to the top in overdrive without touching the gear lever. Our minimum speed was 46mph and the climb took 3min 19sec; a reduction of 12".

Our third run was with the engine set up as a 370ESP It was just possible to detect a hump in the back as the engine kicked in to the high-torque. 1,5501bft mode. We duly crested the hill in 3inin 2sec at a minimum 51inph.

Fresh from our runs with ESP we got behind the wheel of one of the latest Kenworth T600Bs, powered by a HighTorque 365MT with a Fuller 10-speed box and geared for 60mph at 1,425rpm.

Loaded to 35.3 tonnes we set off from Mossville south on Highway 29 following the Illinois River valley The route was chosen to take us up Caterpillar's regular 3% test grade just outside of Mossville. We were running with a 365 owner-driver spec Multi-Torque engine, equipped with Caterpillar's ECAP diagnostic tool which allows a technician to look at various functions within the engine's electronics.

For our first run one of the sensor wires to the electronic control module was disconnected, disabling the Multi-Torque feature and relegating the engine to a standard 365.

The hill was entered at 58mph and the grade slowed the truck steadily When the revs fell to 1300rpm a split downshift was made and we took the rest of the hill in ninth, dropping to 41mph.

For the second run Multi-Torque was reconnected.

As the truck reached around 20mph and 1,500rpm the lever was shifted from sixth to seventh. The throttle pedal was pressed down again and the fuel rack position jumped from the previous maximum of14.0 to 15.0, showing that more fuel was being fed to the engine as it entered the high-torque mode. Even so we needed a downshift just before the grade flattened out. "Another 50Ibft would have done it," said Jim Booth Caterpillar's veteran driver trainer, as we sailed up the steepest part of the grade at 45mph at 1,400rpm.

For the rest of our run the Super 10 was left in top—a tribute to the effortless performance of the Multi-Torque.

Multi-Torque differs from the Cummins ESP in that there is no apparent change in performance when going into high-torque mode. With the Cummins there is a perceptible rise in turbocharger whistle and a substantial jump on the boost gauge. In some situations, a driver can even feel a little extra push in the back as the "afterburners" kick in.

Driving the Detroit is different again. We have driven the Cruise Power in the past and found it very similar to the Caterpillar. Once cruise control is engaged so is the high-torque mode. The Detroit 365/430 is a new rating which has a beefier power curve all the way up. The single-rated 430 is a 1993 engine will supersedes the 425 Series 60 four stroke.

Once in the high torque mode the governor senses the engine speed falling and, in its variable-speed mode, opens the throttle to maintain the pre-set speed.

If the grade is steep enough to haul the engine speed down to 1,100rpm DDEC's cruise control will kick out and the fuel will be cut back. That can be disconcerting when it happens as the engine suddenly loses power, so it's important to change down before this point. Once the shift is completed cruise control "resume" is hit and the electronics opens the throttle again. This hightorque selection through cruise control can be accessed all the way down to around 25mph, when cruise control no longer functions. If the truck speeds up when a downshift is made other control functions within DDEC make sure the engine does not overspeed.All three packages get the job done: as far as fleet operators are concerned it's the fuel economy differences that will swing the balance.

As aumnins predicted, there is a trade-off with the ESP over the baseline rating. In our brief test. which was hardly long enough for a definitive fuel measurement, we recorded 62mpg for the 310 E, 5.8 for the 310 ESP and 5.3 for the 370 ESP. Over our test route we spent an unusual proportion of our time accelerating and climbing hills. The economy of all these engines would be significantly improved in general freight operations. At the top end the Cat 365MT's fuel curve exactly overlays the standard 365's, showing there is no fuel penalty for Multi-Torque at the higher speeds.

As the engine lugs down and the higher torque (and horsepower) is used at lower speeds below 1,400 rpm fuel usage rises compared with the single-rated engine. However, the difference is said to be less than 3% in the worst case.

Offsetting this additional fuel demand is the fact that in many cases a downshift has been avoided. This almost always results in fuel savings, because the engine invariably operates more efficiently at low revs/high power demand, such as when lugging up a hill. That should bear out Caterpillar's contention that the 3E5 Multi-Torque offers better fuel economy than a single rated 425, for instance.

CONCLUSION

ESP concept represents a significant technical achievement by Cummins. Like Cat's and Detroit's engines, ESP has the ability to deliver the fuel economy of a gaffer's motor with the performance usually reserved for the discerning owner-driver.

If the owner is also the driver he can gain many of the multi-rating features by driving a high-horsepower engine like the computers do. The trick is staying out of the horsepower at the top end, restricting cruising speed and using the high torque to lug up the hills without shifting But that kind of driving takes takes discipline. A multi-profile engine can remove the the need for that discipline

Cummins has not set a European launch date for ESP, promising only to "evaluate the concept". Given the obvious benefits of this thinking engine, we hope Cummins won't spend too much time thinking before making it available to hauliers outside the US. Eli by Steve Sturgess