HEAVY BURDEN

Page 38

Page 39

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

permines recovery operator Alan Sewell is worried that his firm—and other recovery operators specialising in heavy trucks—could be in danger of falling foul of Construction and Use Regulations every time a vehicle is rescued when the combined weight of the "casualty" and the recovery vehicle exceeds permitted axle loading weights.

The regulations are largely silent on the status of recovery vehicles except to exempt them from 0-licence and tachograph requirements. But Sewell believes that he runs the risk of being ordered by police in one county to move a vehicle, only to find police in the next county stopping his driver for overloading.

"Somewhere on a scale of between half a tonne and 38 tonnes it becomes impossible to recover vehicles within the regulations," he claims. "If we join two vehicles together they are controlled by one driver, taking them into the area of Special Types.

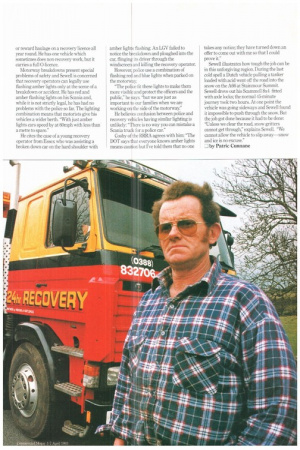

"Also with a loaded four-axle the load may have come forward which puts extra weight on the front axles of the casualty" says Sewell—not that he's worried about the safety of his operation, based in Toft Hill, Durham.

DESIGN WEIGHT

He reckons the design weight of one of his heavy pieces of kit—such as his Scania 143E—far exceeds the requirements of the Contruction and Use Regulations.

What Sewell is after is a change to the regulations allowing recovery vehicles to be plated as Special Types for the purpose of unblocking a road in an emergency The present Special Types regulations require two days' notice to shift a load. This clearly would be no use to recovery men: "We don't know when an accident is going to happen," says Sewell.

The campaign is not exclusively his. The Road Rescue Recovery Association, of which Sewell is a member, and the Association of Vehicle Recovery Operators have both lobbied the Department of Transport. but to no avail.

RRRA chairman Peter Cosby says some progress was made in convincing the DOT that recovery vehicles should be treated as Special Types with a move to an 80-tonne train weight and a width allowance of 2.9m, but the initiative has stalled. There is a likelihood, however, that operators could be allowed a tractor unit at recovery rates for rescuing artic trailers. This would not solve the problem of eight-wheelers: "What are you going to do—trans-ship on the M25?" asks Cosby.

In addition to a Special Types plate, Sewell believes it should be mandatory for manufacturers of recovery vehicles to issue operators with a plate detailing the design weight if the vehicle is required to operate outside normal Construction and Use Regulations.

The police have not yet stopped any of Sewell's vehicles for overloading, but he worries that insurance companies, which are increasingly putting the screws on customers, may be tempted to take a tougher line: "They could refuse to pay if a court case proved the vehicle was running overweight. There is always a first time; I feel we are wide open."

Sewell believes the loading regulations as they stand for recovery operators also penalise operations which add additional equipment to do the job as safely as possible. He cites the example of fitting a Telma retarder to boost braking power: It avoids friction but it weighs quite heavy."

Recovering an artic requires its front axle to be lifted and its brakes connected so that it can be stopped easily . A rigid four or sixaxle truck is more of a problem in that it could be fully loaded up to 32 tonnes. "We need a heavy vehicle with big brakes on the front to rescue the casualty but if the casualty is 32 tonnes we can only legally go up by six tonnes."

Suggestions that broken-down vehicles are unloaded before being moved are not practical, Sewell points out: "We picked up a compactor running at 30 tonnes gross recently. It was full of refuse—no one wants that spread about."

Increased EC vehicle weights will put additional pressure on recovery operators with five-axle art ics legally permitted to run at 40 tonnes by the end of 1998 and vehicles carrying an ISO container permitted to run at 44 tonnes. "We will still be expected to recover these vehicles," says Sewell. Recovery men in the Pennines face a "different ballgame" from operators in flatlands such as the M25, Lincoln or Norfolk, he points out: "We have to have the power and strength; down there you can afford to run on less power."

Sewell would like to see pressure put on the cowboys in his industry by introducing 0-licences. He also believes that the £85 VED paid by a recovery vehicle, compared with up to 45,000 for a 38-tonner on general haulage, allows anyone to set themselves up in recovery: "We call them hawker boys," remarks.

Sewell accuses some of these outfits of blatantly abusing the system by running hire or reward haulage on a recovery licence all year round. He has one vehicle which sometimes does non-recovery work, but it carries a full 0-licence.

Motorway breakdowns present special problems of safety and Sewell is concerned that recovery operators can legally use flashing amber lights only at the scene of a breakdown or accident. He has red and amber flashing lights on his Scania and, while it is not strictly legal, he has had no problems with the police so far. The lighting combination means that motorists give his vehicles a wider berth. "With just amber lights cars speed by at 60mph with less than a metre to spare."

He cites the case of a young recovery operator from Essex who was assisting a broken down car on the hard shoulder with amber lights flashing. An LGV failed to notice the breakdown and ploughed into the car, flinging its driver through the windscreen and killing the recovery operator.

However, police use a combination of flashing red and blue lights when parked on the motorway.

"The police fit these lights to make them more visible and protect the officers and the public," he says. "but we are just as important to our families when we are working on the side of the motorway."

He believes confusion between police and recovery vehicles having similar lighting is unlikely: "There is no way you can mistake a Scania truck for a police car."

Cosby of the RRRA agrees with him: "The DOT says that everyone knows amber lights means caution but I've told them that no one takes any notice; they have turned down an offer to come out with me so that I could prove it."

Sewell illustrates how tough the job can be in this unforgiving region. During the last cold spell a Dutch vehicle pulling a tanker loaded with acid went off the road into the snow on the A66 at Stainrnour Summit. Sewell drove out his Scarnmell 8x4 fitted with axle locks-, the normal 45-minute journey took two hours. At one point the vehicle was going sideways and Sewell found it impossible to push through the snow. But the job got done because it had to be done: "TJnless we clear the road, snow gritters cannot get through," explains Sewell. "We cannot allow the vehicle to slip away—snow and ice is no excuse."

by Patric Cunnane