B ATTERY-ELECTR1CS are still sometimes thought of as slow, cumbersome, short-range

Page 38

Page 39

Page 40

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

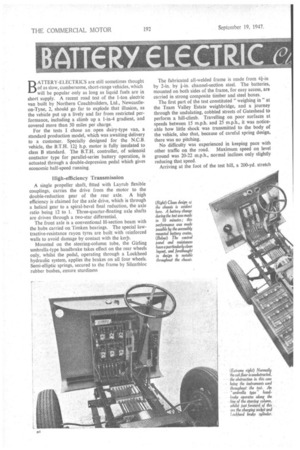

vehicles, which will be popular only as long as liquid fuels are in short supply. A recent road test of the 1-ton electric van built by Northern Coachbuilders, Ltd., Newcastleon-Tyne, 2, should go far to explode that illusion, as the vehicle put up a lively and far from restricted performance, including a climb up a 1-in-4 gradient, and covered more than 50 miles per charge.

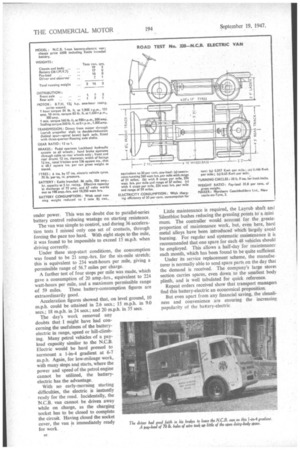

For the tests I chose an open dairy-type van, a standard production model, which was awaiting delivery to a customer. Specially designed for the N.C.B. vehicle, the B.T.H. in h.p. motor is fully insulated to class B standard. The B.T.H. controller, of solenoid contactor type for parallel-series battery operation, is actuated through a double-depression pedal which gives economic half-speed running.

High-efficiency Transmission A single propeller shaft, fitted with Layrub flexible couplings, carries the drive from the motor to the double-reduction gear of the rear axle. A high efficiency is claimed for the axle drive, which is through a helical gear to a spiral-bevel final reduction, the axle ratio being 12 to 1. Three-quarter-floating axle shafts are driven through a two-star differential.

The front axle is a conventional H-section beam with the hubs carried on Timken bearings. The special lowtractive-resistance rayon tyres are built with reinforced walls to avoid damage by contact with the kerb.

Mounted on the steering-column tube, the Girling umbrella-type handbrake takes effect on the rear wheels only, whilst the pedal, operating through a Lockheed hydraulic system, applies the brakes on all four wheels. Semi-elliptic springs, secured to the frame by Silentbloc rubber bushes, ensure sturdiness The fabricated all-welded frame is made from 4i-in by 2-in. by k-in. channel-section steel. The batteries, mounted on both sides of the frame, for easy access, are carried in strong composite timber and steel boxes.

The first part of the test constituted "weighing in" at the Team Valley Estate weighbridge, and a journey through the undulating, cobbled streets of Gateshead to perform a hill-climb. Travelling on poor surfaces at speeds between 15 m.p.h. and 25 m.p.h., it was noticeable how little shock was transmitted to the body of the vehicle, also that, because of careful spring design, there was no pitching.

No difficulty was experienced in keeping pace with other traffic on the road. Maximum speed on level ground was 20-22 m.p.h., normal inclines only slightly reducing that speed.

Arriving at the foot of the test hill, a 200-yd. stretch

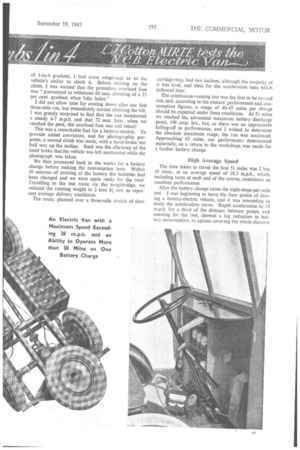

of 1-in-4 gradient, I had some misgivingS as to the vehicle's ability to climb it. Before starting on the climb, I was warned that the protective overload fuse was "guaranteed to withstand 60 secs. climbing of a 25 per cent, gradient when fully laden."

I did not allow time for cooling down after our fast three-mile run, but immediately started climbing the hill. I was greatly surprised to find that the van maintained a steady 6-7 m.p.h. and that 72 secs. later, when we reached the peak, the overload fuse was still intact!

This was a remarkable feat for a battery-electric. To provide added conviction, and for photographic purposes, a second climb was made, with a hand-brake test half way up the incline. Such was the efficiency of the hand brake that the vehicle was left unattended while the photograph was taken.

We then journeyed back to the works for a battery change before making the consumption tests. Within 10 minutes of arriving at the factory the batteries had been changed and we were again ready for the road Travelling to the test route via the weighbridge, we reduced the running weight to 2 tons 81 cwt. to represent average delivery conditions.

The route, planned over a three-mile stretch of dual carriage-way, had two inclines, although the majority of it was level, and ideal for the acceleration tests which followed later.

The continuous-running test was the first to be cal led out, and, according to the makers' performance and consumption figures, a range of 40-45 miles per charge should be expected under these conditions. At 51 miles we reached the advocated maximum battery discharge point, 198 amp. hrs.; but, as there was no appreciable falling-off in performance, and I wished to determine the absolute maximum range, the run was continued. Approaching 63 miles, our performance deteriorated materially, so a return to the workshops was made for a further battery change.

High Average Speed The time taken to travel the first 51 miles was 2 hrs 45 mins., at an average speed of 18.5 m.p.h., which, including turns at each end of the course, constitutes an excellent performance.

After the battery change came the eight-stops-per-mile test. I was beginning to learn the finer points of driving a battery-electric vehicle, and it was interesting to study the acceleration curve. Rapid acceleration to l5 m.p.h. for a third of the distance between points, and coasting for the rest, showed a big reduction in battery consumption, as against covering the whole distance

under power. This was no doubt due to parallel-series battery control reducing wastage on starting resistance.

The van was simple to control, and during 36 acceleration tests I missed only one set of contacts, through forcing the pace too hard. With eight stops to the mile. it was found to be impossible to exceed 15 m.p.h. when driving correctly.

Under these stop-start conditions, the consumption was found to be 21 amp.-hrs. for the six-mile stretch; this is equivalent to 234 watt-hours per mile, giving a permissible range of 56.7 miles per charge.

A further test of four stops per mile was made, which gave a consumption of 20 amp.-hrs., equivalent to 224 watt-hours per mile, and a maximum permissible range of 59 miles. These battery-consumption figures are extraordinarily good.

Acceleration figures showed that, on level ground, 10 m.p.h. could be attained in 2.6 secs.; 15 m.p.h. in 9.0 secs.; 18 m.p.h. in 24 secs.; and 20 m.p.h. in 35 secs.

The day's work removed any doubts that I might have had concerning the usefulness of the batteryelectric in range, speed or hill-climbing. Many petrol vehicles of a payload capacity similar to the N.C.B. Electric would be hard pressed to surmount a 1-in-4 gradient at 6-7 m.p.h. Again, for low,mileage work, with many stops and starts, where the power and speed of the petrol engine cannot be utilized, the batteryelectric has the advantage.

With no early-morning starting difficulties, the electric is instantly ready for the road. Incidentally, the N.C.B. van cannot be driven away while on charge, as the charging socket has to be closed to complete the circuit Having dosed the socket cover, the van is immediately ready for work.

Little maintenance is required, the Layrub shaft and Silentbloc bushes reducing the greasing points to a mini mum. The controller would account for the greatei proportion of maintenance work, but, even here, hard metal alloys have been introduced which largely avoid burning. For regular and systematic maintenance it is recommended that one spare for each 48 vehicles should be employed. This allows a half-day for maintenance each month, which has been found to be quite sufficient

Under its service replacement scheme, the manufacturer is normally able to send spare parts on the day that the demand is received. The company's large stores section carries spares, even down to the smallest body plinth, and is well tabulated for quick reference.

Repeat orders received show that transport managers find this battery-electric an economical proposition.

But even apart from any financial saving, the cleanliness and convenience are ensuring the increasing popularity of the bakery-electric