SOME DEFECTS OF EARLY DESIGN.

Page 10

Page 11

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

How the Defects were Gradually Discovered and Eliminated.—II.

IN THE FIRST portion of this article, dealing with some of the shortcomings of pioneer type commercial vehicle engines and their accessories, it was pointed out how, in many cases, imperfection in one element of the complete design, by throwing extra and unforeseen work on to adjacent parts, interacted to throw into relief these, in other respects, minor faults.

In considering the matter of clutch design, we are immediately confronted with still another case in point, for the sometimes very crude type of clutch fitted to early vehicles was called upon totransmit the torque from an engine which, in the light of modern standards, was simply an abomination in the matter of smooth and even running. In fact such terms were better omitted in any discussion of their performances, as being somewhat incongruous.

The friction clutch is, in its very nature, a necessary evil; in other words, it is only rendered necessary at all by reason of the essentially imperfect nature of the internal-combustion engine, as at present developed, which is unable to exert appreciable torque at very low speeds and therefore unable to move the car from a, state of rest without the intervention of . some device which enables the motor to revolve at a sufficient speed to exert useful power, this power being transmitted as gradually and smoothly as may be, whilst the speed of the clutch shaft is being accelerated from zero to that of the engine. This, of itself, is not an easy proposition to meet satisfactorily, even granting a modern flexible and smooth running engine, the difficulty, of course, resting in gradually imparting movement to the clutch shaft against the heavy resistance incidental to moving a loaded vehicle from rest. When, on the other hand, it is required to deal with a snorting monstrosity which, on the throttle being opened as gently as possible, inseries of violent pulsations and works itself into a perfury sufficient to cause any the immediate vicinity to requires no effort of the dulges in a and splutterings feet paroxysm of restive Verse in bolt forthwith, it imagination to conceive the difficulties in the path of the designer when endeavouring to transfer this forty odd wildhorse-power, with anything less than a correspondingly violent jerk, to the much abused transmission gear.

The type of clutch most commonly fitted in the early days was identical with that which is still most in favour with the majority of designers, viz., the fabric or leather-to-metal cone.

The survival of this type is due primarily to its extreme simplicity and also to the fact that, when properly proportioned and well made, it is extremely hard to beat for efficiency and durability.

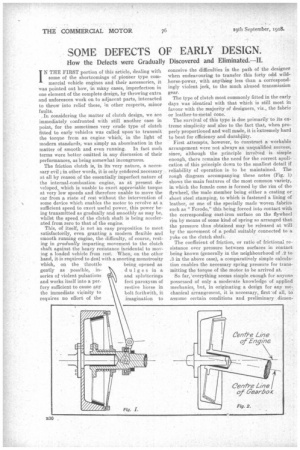

First attempts, however, to construct a workable arrangement were not always an unqualified success, since, although the principle involved is simple enough, there remains the need for the correct application of this principle down to the smallest detail if reliability of operation is to be maintained. The rough diagram accompanying these notes (Fig. 1) shows the main features of the most common variety, in which the female cone is formed by the rim of the flywheel; the male member being either a casting or sheet steel stamping, to which is fastened a lining of leather, or one of the specially made 'woven fabrics such as "Foredo," this being forced into contact with the corresponding cast-iron surface on the flywheel rim by means of some kind of spring so arranged that the pressure thus obtained may be released at will by the movement of a pedal suitably connected to a yoke on the clutch shaft.

The coefficient of friction, or ratio of frictional resistance over pressure between surfaces in contact being known (generally in the neighbourhood of .2 to .3 in the above case), a comparatively simple calculation enables the necessary spring pressure for transmitting the torque of the motor to be arrived at.

So far, 'everything seems simple enough for anyone possessed of only a moderate knowledge of applied mechanics, but, in originating a design for any mechanical arrangement, it is necessary, first of all, to ass111110 certain conditions and preliminary dimen sional limits, in order to form, as it were, a foundation for the whole.

In this case, for instance, a suitable diameter of cone must be chosen, and, this being assumed, various angles of cone may be used, which will, according to the principles of mechanics, give a varying intensity of pressure between the surfaces in contact, with a certain strength of spring.

Here we meet with one of the points upon which some of our early rule-of-thumb designers fell into error.

It is quite obvious that there must be some higher limit to this intensity of pressure beyond which durability of the clutch lining will be affected. This excessive pressure is met .with if, for example, the diameter of the cone is insufficient, the torque transmitted varying inversely as the effective radius, and restriction in this direction must be compensated for by greater contact pressure.

Many early clutches were undoubtedly too small for the power transmitted, leading to the use of very heavy springs, or alternatively an excessively small cone angle in order to prevent slip.

The excess of pressure thus brought about caused undue compression of the leather, the material mainly used in those days, with the result that slipping of the clutch when taking up the drive, etc., caused burning and glazing of the surface fibres. This, in turn, led to a reduction a the friction 'coefficient, and so, to rapid destruction of the material through slipping under load, the clutch meanwhile becoming harsh and jerky in action.

It may be inferred from the above that a cone clutch should be of as large diameter as reasonably possible, the extra flywheel effect thus obtained being an additional advantage, tending to smoother running of the engine.

Modern clutches of good design impose a comparatively slight intensity of pressure on the engaging surfaces, from 7 to 10 lb. per sq. in. being an ideal figure. Many earlier types, on the contrary, necessitated a pressure of 40 to 60 lb. per sq. in., or even more in some extremely bad cases.

With the lower figure named and using " Ferodo " or similar material, the life of a clutch lining, with fair use, is practically indefinite, and, with a cone angle of about 12 degrees to 15 degrees operation of the clutch is smooth and harshness in pick-up avoided.

The unpleasant and, from the point of view of the transmission, very undesirable jerk at starting so common at one time is now seldom met with ; in fact, with some designs it is impossible to produce this effect even should no attempt be made to engage the clutch gradually.

This latter property is, to some extent, assisted by forming both the flywheel and cone with a solid disc, which causes a kind of " dashpot " effect 'during engagement by reason of the air contained between these two parts being forced to escape between the friction surfaces at the moment of contact, thus forming an air cushion, which effectively prevents any sudden seizure between the stationary cone and the rapidly revolving flywheel.

Another oonstant source of trouble wat due to lack of sufficient provision for lubricating the spigot bearing, this important point being often strangely overlooked with annoying results. Inadequate bearing surface here was also a contributory cause of seizure. With regard to the clutch spring, this is now invariably 'arranged so that the reaction is scIf-contained within the flywheel, that is to say, so as not to cause an end thrust on the crankshaft except whilst the clutch is disengaged. In some early models this was not the case, with the result that trouble often developed within the crankcase.

Yet another fruitful source of roadside stoppages was the seizure of the thrust collar, or yoke, transferring the pedal pressure to the clutch spring when declutching. This part is often constantly in action, due to the driver resting his foot on the clutch pedal whilst running.

IF, as was often the case, this bearing consists merely of a plain metal washer inadequately lubricated and protected, it is not surprising that what little grease was present at starting was soon dissipated by the action of centrifugal force, with the usual consequence that the yoke, which was designed to be stationary, would suddenly evince a desire to revolve in close company with the adjacent collar on the clutch shaft, to 'the -general detriment ot neighbouring parts and involving yet another item in the disgusted owner's repair account. The obvious remedy, of course, is to fit a ball-thrust which can, if called upon, operate without any lubricant at all.

It is the exception in these days not to find between the clutch and gearbox a properly designed double universal joint, which effectually neutralizes any want of alignment between the components.

In the young days of motoring, however, this was not by any means the rule, the somewhat unpractised designers of that period being evidently of the opinion that, because engine and gearbox could be accurately lined up during erection of the chassis on an apparently rigid frame, this state of affairs would always obtain, forgetting that, on the road, no frame behaves as a rigid structure for many moments together and that occasionally this member undergoes surprising contortions, leaving the various parts of the .transmission, which were originally in correct alignment, decidedly at variance with one another.

Under such oonditions, of course, a smooth and satisfactory clutch actuation is an impossibility, since cross-binding is sure to occur on the spigot bearing, and, should this.be even slightly worn, the concentricity of these two parts is destroyed, as is shown in Fig. 2, a state of affairs which scarcely tends to improve the smoothness of action so much to be desired. Such items as accessibility for repairs and adjustments should not, of course, be overlooked, and yet, what ought to be the simple operation of adjusting the clutch spring was, at one time in many cases, a task requiring a considerable amount of contortion on the part of the mechanic, accompanied by the usual supply of bad language! Nowadays, adjustment and renewal of linings are not only much easier but, what is perhaps more important, are very seldom required. Touching this matter of adjustment, it is, perhaps, not superfluous to point out that, in a well designed clutch, it should not be possible to tighten up the actuating spring to such an extent as unduly to increase the pressure above that required to transmit the power of the motor, otherwise some drivers will undoubtedly be found who, in their desire to avoid slip, will take .advantage of all the adjustment allowed, thereby unnecessarily stressing the operating tear and reducing the working life of the friction lining. In the next instalment of this article it is proposed to deal with some of the weak points which were to be found formerly in gearbox design. LIVE AILI:E.