Paul Mungo takes a look at the latest techniques used in mode ay warehousing

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

IT'S BEEN said that the ideal solution in warehousing is to eliminate the warehouse altogether. To the transport industry the warehouse is a bottleneck that interrupts the efficient movement of goods; to the distributor the stock held in a warehouse represents capital lost and high storage costs.

But granted that there is no eliminating the need for ware

housing, then the solution is to make the most efficient use of it possible. For the transport industry a warehouse can be a profitable sideline -indeed, one transport firm reports that their warehousing operation creates 80 per cent of their revenue -while for the distributor, there are savings and profits inherent in carrying adequate stocks to meet customer demands.

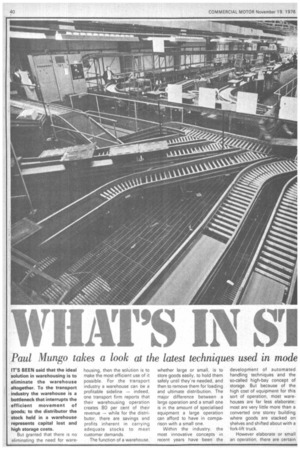

The function of a warehouse, whether large or small, is to store goods easily, to hold them safely until they're needed, and then to remove them for loading and ultimate distribution. The major difference between a large operation and a small one is in the amount of specialised equipment a large operation can afford to have in comparison with a small one.

Within the industry, the most innovative concepts in recent years have been the development of automated handling techniques and the so-called high-bay concept of storage. But because of the high cost of equipment for this sort of operation, most warehouses are far less elaborate; most are very little more than a converted one storey building where goods are stacked on shelves and shifted about with a fork-lift truck.

However elaborate or small an operation, there are certain factors and methods common to every size of warehouse. Storage facilities depend on the most effective use of the available cubic space, at minimum cost, compatible with the required speed of operation, and meeting the degree of accessibility desired The most efficient use of space is by stacking pallet loads one on top of another, the higher the better. This solution, unfortunately, is rarely applica ble. Most goods are too fragile or unstable to be stacked, access to a 'particular load is limited, and racking has become the commonly accepted practice in the industry.

Racking

Most commercially produced racking these days is of the so-called adjustable type, making it quick to set up or take down. Perfectly suitable to smaller operations, it can be installed to heights of 40ft, or even more, depending, of course, on the weights of the loads.

For high-bay automated warehousing, however, it becomes essential to use structural steel precision built shelving. In an automated system the fork insertion is automatic and must therefore be accurately aligned.

However, the development of high-bay storage is far more advanced in other industrial nations than in the UK, despite evidence that it can reduce labour costs and speed the flow of goods.

There is some reluctance among British distribution managers to invest in such costly systems, especially in the present economic climate and with growing evidence of worker resistance to innovations of this sort.

Most of the automated systems are computer-operated, controlling the stacker cranes and the conveyors that serve the high bay area. More complex systems handle the order inward and goods outward operations as well, though the capital outlay on such systems make them prohibitive for all but the largest warehouses that need fast and accurate handling and load selection.

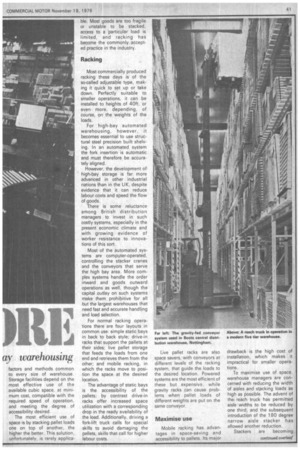

For normal racking operations there are four layouts in common use: simple static bays in back to back style; drive-in racks that support the pallets at their sides; live pallet storage that feeds the loads from one end and retrieves them from the other; and mobile racking, in which the racks move to position the space at the desired location.

The advantage of static bays is the accessibility of the pallets; by contrast drive-in racks offer increased space utilization with a corresponding drop in the ready availability of the load. Additionally, driving a fork-lift truck calls for special skills to avoid damaging the pallets, skills that call for higher labour costs. Live pallet racks are also space savers, with conveyors at different levels of the racking system, that guide the loads to the desired location. Powered systems are the most efficient of these but expensive, while gravity racks can cause problems when pallet loads of different weights are put on the same conveyor.

Maximise use

Mobile racking has advantages in space-saving and accessibility to pallets. Its major drawback is the high cost of installation, which makes it impractical for smaller operations.

To maximise use of space, warehouse managers are concerned with reducing the width of aisles and stacking loads as high as possible. The advent of they reach truck has permitted aisle widths to be reduced by one third, and the subsequent introduction of the 180 degree narrow aisle stacker has allowed another reduction.

Stackers are becoming increasingly popular because they can work in aisles little wider than the pallet itself -and can lift to considerable heights, often as much as 100ft. Their chief disadvantage is that without expensive transfer devices they can only work one aisle, meaning that each aisle needs its own.stacker.

A compromise solution has been to use narrow aisle trucks that have a lower lift height, but the advantage of working different aisles. Some narrow vehicles can, if necessary, do general vehicle loading and unloading as well.

A new development is a semi-automatic system for positioning lifting vehicles in the aisle, so the operator has only to actuate the forward or reverse controls. An indicator will show him when he is aligned, and he merely presses a button to lift the load.

Horizontal movement It has become a cliché to refer to the counter-balanced fork-lift truck as the workhorse. of the industry. It is the most versatile piece of equipment, capable of stacking loads as well as picking them up from lorries, either between ground level and deck or from within the lorry with the aid of a ramp.

The front-loading fork -lift truck still is the most popular of this sort of vehicle, with electric and internal combustion engines the favored power sources. The versatility and adaptability of these vehicles is constantly being expanded with innovations and attachments, so many now that the "basic" fork-lift truck can carry Out a number of specialized tasks.

There is, however, a growing awareness among users that the fork-lift truck can be very expensively misused in applications where high-speed, intensive operation is required. It has become apparent that, like every other mechanical aid, the fork-lift cannot reach its optimum performance unless tied in with other equipment that complement the fork-lift's' versatility.

Accordingly, many companies now choose a mixture of material handling equipment to create the smoothest operation possible. Hand-pallet trucks and stackers, for instance, are used to retrieve pallet loads from vehicles; counter-balanced .fork-lifts carry the loads to pick-up stations, and lifting equipment is then used to store goods. In this way the various operations within the chain are carried out by equipment best suited for that particular job, but at the same time there is enough flexibility in the system to take care of 'breakdowns or particularly busy times.

More sophisticated operations can use the extremely specialised equipment that exists to move goods. Overhead cranes, mobile gantries, self-loading vehicle systems, telescopic. conveyors and towline conveyors each have their role in certain situations.

Other systems include tractor/trailer trains that can carry a number of pallets each trip. applicable for use in very busy operations. And more companies are looking at driverless tractor systems as a method of reducing labour costs. These systems can be simple two station affairs or far more complex circuits with a number of stops.

Options

Warehousing, to summarise in twenty-five words or less, is the search for a workable compromise. The compromise applicable to one warehouse operation may not be — and probably is not — the solution that will work elsewhere.

The small warehouse will probably have to use a fork-lift • rtick for receipt and despatch of goods as well as in the actual storage operation. The medium-sized warehouse, as well as the larger warehouse, will be able to look at more specialised equipment to increase their throughput. But the problems inherent in reaching a solution are common to all warehouses; and in the compromise solution should be the approach that fits the requirements of the particular operation.