Dodge K800 Tipper

Page 54

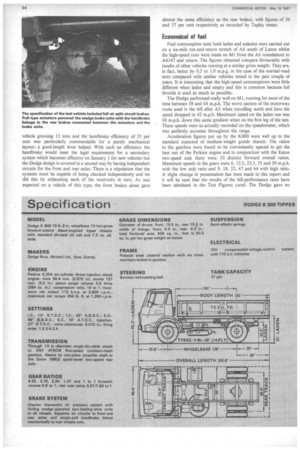

Page 55

Page 56

Page 59

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

By A. J. P. Wilding,

AMIMechE, MIRTE

WITH all the emphasis nowadays on maximum-gross attics it can often be forgotten that medium-weight trucks will continue as the second largest section numerically in transport, exceeded only by those engaged solely on local delivery work. It is the practice cf manufacturers of medium-weight vehicles to offer a range of models based on the same general design extending from around 5 tons carrying capacity to 16-ton-gross fourwheel rigids as well as tractive unit versions, and typical of these is the Dodge 500 Series which was introduced in September 1965.

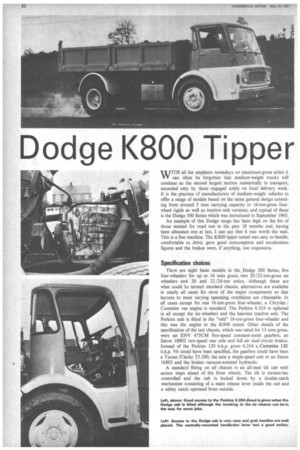

An example of this Dodge range has been high on the list of those wanted for road test in the past 18 months and, having been allocated one at last, I can say that it was worth the wait. This is a fine machine. The K800 tipper tested was easy to handle, comfortable to drive; gave good consumption and acceleration figures and the brakes were, if anything, too responsive.

Specification choices

There are eight basic models in the, Dodge 500 Series, five four-wheelers for up to 16 tons gross, two 20/22-ton-gross six wheelers and 20 and 22/24-ton artics. Although these are what could be termed standard chassis, alternatives are available in nearly all cases for most of the major components so that layouts to meet varying operating conditions are obtainable. In all cases except for one 16-ton-gross four-wheeler, a Chrysler/ Cummins vee engine is standard. The Perkins 6.354 is optional in all except the six-wheelers and the heaviest tractive unit. The Perkins unit is fitted in the "odd" 16-ton-gross four-wheeler and this was the engine in the K800 tested. Other details of the specification of the test chassis, which was rated for 13 tons gross, were an ENV 475 CM five-speed constant-mesh gearbox, an Eaton 18802 two-speed rear axle and full air dual-circuit brakes. Instead of the Perkins 120 b.h.p. gross 6.354 a Cummins 130 b.h.p. V6 could have been specified, the gearbox could have been a Turner /Clarke T5.300, the axle a single-speed unit or an Eaton 16802 and the brakes vacuum-assisted hydraulic.

A standard fitting on all chassis is an all-steel tilt cab with access steps ahead of the front wheels. The tilt is torsion-bar controlled and the cab is locked down by a double-catch mechanism consisting of a main release lever inside the cab and a safety catch operated from outside. Braking on the model tested was by a split system through a dual foot valve and independent circuits (including reservoirs) to each of the axles; Girling wedge-actuated brake units are used all round.

All tests were carried out in an area south of Luton, the load consisting of gravel which came almost to the top of the sides of the 7.5 cu. yd. body. Weight of the load was 7 tons 6.75 cwt. and with two men in the cab as well as the driver this brought the gross weight to just over the 13 tons limit placed on the model by Dodge. The gravel was not perfectly evenly spread, there being extra at the rear end but this had been done to bring the weight at the driving-axle wheels to the 9 tons legal maximum.

A braking puzzle

Brake tests were carried out first and after a couple of stops from 20 m.p.h. which produced locking of the rear wheels, a maximum-pressure stop from 30 m.p.h. caused all wheels to lock and the tyres to leave heavy marks for some 45 ft. behind the vehicle. This was on a road which normally has good adhesion characteristics but it may have been that hot weather on the day of the test had caused a change. It was decided to repeat the tests on another road surface and here the figures quoted in the specification table were obtained. It is interesting that the stopping distance from 30 m.p.h. on the first surface where the wheels had locked had been 72 ft. whereas on the second road the figure was consistently around 60 to 61 ft. from the same speed.

The figures for peak deceleration as recorded by Tapley meter were 76 per cent from 20 m.p.h. and 70 per cent from 30 m.p.h. and there were indications that some adjustment was required in the brakes. This can be said because heavy marks 15 ft. long were made by the driving-axle wheels on the stops from 20 m.p.h. whilst on the stop from 30 only the offside tyres marked the road heavily —for some 40 ft. With perfect adjustment it is likely that better figures would have resulted; it is also probable that if there had been less effort at the driving wheels, the figures could have been better still. The fact that stopping distances are extended when the wheels lock as against when they are at the point just before locking was illustrated on the initial test, as already pointed out.

Even so, the braking figures obtained were very good for a vehicle grossing 13 tons and the handbrake efficiency of 33 per cent was particularly commendable for a purely mechanical layout; a good-length lever helped. With such an efficiency the handbrake would meet the legal requirement for a secondary system which becomes effective on January 1 for new vehicles but the Dodge design is covered in a second way by having independent circuits for the front and rear axles. There is a stipulation that the systems must be capable. of being checked independently and we did this by exhausting each of the reservoirs in turn. As was expected on a vehicle of this type, the front brakes alone gave almost the same efficiency as the rear brakes, with figures of 36 and 37 per cent respectively as recorded by Tapley meter.

Economical of fuel

Fuel consumption tests both laden and unladen were carried out on a six-mile out-and-return stretch of A6 south of Luton whilst the high-speed runs were made on M1 from the A6 roundabout .to A4147 and return. The figures obtained compare favourably with results of other vehicles running at a similar gross weight. They are, in fact, better by 0.5 to 1.0 m.p.g. in the case of the normal-road tests compared with similar vehicles tested in the past couple of years. It is interesting that the high-speed consumptions were little different when laden and empty and this is common because full throttle is used as much as possible.

The Dodge performed really well on Ml, running for most of the time between 58 and 64 m.p.h. The worst section of the motorway route used is the hill after A5 when travelling north and here the speed dropped to 42 m.p.h. Maximum speed on the laden run was 69 m.p.h. down this same gradient when on the first leg of the test. These speeds were as actually recorded on the speedometer, which was perfectly accurate throughout the range.

Acceleration figures put up by the K800 were well up to the standard expected of medium-weight goods chassis. The ratios in the gearbox were found to be conveniently spaced to get the best out of the Perkins engine and in conjunction with the Eaton two-speed axle there were 10 distinct forward overall ratios. Maximum speeds in the gears were 6, 12.5, 22.5, 35 and 50 m.p.h. with the low axle ratio and 9, 18, 32, 47 and 64 with high ratio. A slight change in presentation has been made in this report and it will be seen that the results of the hill-performance tests have been tabulated in the Test Figures f anel. The Dodge gave no

trouble on the hill climb and an easy gear change helped in producing a satisfactory time for the ascent of Bison Hill. The 61 per cent efficiency on the fade tests when compared with the 76 per cent on the cold-drum tests shows that the design should have plenty in hand when operated in conditions likely to produce fade.

The Dodge K800 is a pleasant vehicle to drive, easy to handle, with a good "feel" to the brakes and with plenty of performance. Steering felt a bit stiff, which was surprising in view of the low gearing-7.5 turns from lock to lock, but there was a very good lock which made maneouvering easy. All-round visibility I found to be excellent and the use of only narrow pillars between the large central rear window and curved rear quarter lights gave the effect of full all-round vision.

The top of the windscreen is relatively low on the Dodge cab which could be a point of criticism for very tall drivers, but I found no problem and in fact on a very bright and sunny day it was a help in reducing glare. Mirror equipment is well.up to the normal standard. I prefer convex mirrors but when I had repositioned that on the offside so that it was visible through the door quarter light instead of being partly masked by the pillar between this and the main door window I found that an adequate view to the rear could be obtained. The cab used by Dodge on the 500 Series does not have the standard of luxury of some other unitS currently available but it is nevertheless a great improvement on what used to be offered by most British makers and is more than adequate for even the most particular driver and especially for a cab on a hardworking tipper. The roof is lined and the floor is covered with rubber mats, but the remaining interior surfaces are simply painted. This does not detract from the appearance. Seating is adequate—there was the optional two-man passenger seat on the test chassis—without being pretentious, and a good point is that adequate storage for a driver's bits and pieces is provided on the left-hand side of the facia.

The instruments are well-placed in front of the driver and as well as a speedometer and mileage recorder there are water temperature, fuel and dual-air-pressure gauges and an ammeter. There is an ashtray in the centre of the dash and coat hooks and cab light. Access to the cab is easy. Unladen, the first step is 2 ft. 4 in. from the ground and the cab floor is 1 ft. above it. Grab handles on both front corner pillars are of adequate size and well placed.

All controls are also well placed and the clutch, brake and accelerator pedal are light in operation but I noticed that the clutch-pedal rubber pad was worn through at the top corner even though the test vehicle had only covered just over 6,000 miles. This indicates that the angle of the pedal face could with advantage be modified.

Taken all round, the Dodge K800 was found to be a workmanlike machine with a good specification for most types of operation, giving very acceptable facilities for the driver and economy to the operator. As tested, the K800 chassis /cab carries a list price of £2,035. This, includes £270 for the Eaton two-speed axle option and would be increased by £90 for the Cummins engine, and by £55 for the Turner synchromesh gearbox.