The Chancellor's Budget And Yours

Page 56

Page 59

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

Some Examples of How Costs and Rates Will Have to be Increased Are Given in This Article, Which Also Outlines Methods of Calculating New Charges

T0 the haulier, the Budget introduced by Sir Stafford Cripps on April 18 can have only one meaning. Purchase tax on the przce of his new vehicles and the increased cost of fuel, force him, however unwillingly, to increase his rates to cover these new costs. In doing so, he may lay himself open to competition from such hauliers as have not the courage to resist the temptation to charge less than the new commitments justify. In a Budget bulletin circulated to members, Mr. George Irwin, secretary of the Eastern Area of the Road Haulage Association, sums up the situation aptly.

" Unless rates are increased," he says, "the work will be done at a loss and no haulier can afford that for long. Non-members will not receive this recommendation and it may be found that certain hauliers have not increased their rates for the moment. Customers may tell members that other hauliers have not increased their rates. They should not allow this to sway their judgment, for working at a loss does not help to pay for the next gallon of fuel. The more traffic the cut-throat haulier carries at a loss the sooner will he be off the road. The best defence against such competition is vo-operation between reputable hauliers."

There cannot be many operators to-day who are not members of the R.H.A. The times are difficult and the backing of a well-supported trade association can be, and in this case is, very helpful. Nevertheless, it may, be that this article may be read by non-members, and I shall thus be assisting Mr. Irwin's efforts to uphold the prestige of the industry. For obvious reasons I cannot deal in a single article with the difference in operating costs which the Budget will mean to all types and sizes of vehicle in which hauliers are interested. This will in any event be done in the new issue of "The Commercial Motor Tables of Operating Costs" which is in preparation. By taking three typical examples and indicating the increases in these cases I can show the operator how to calculate for himself figures which would apply to his own vehicle.

All three examples will be of 5-6-ton capacity. One is a low-priced, petrol-engined machine and two high-priced vehicles, one petroland one oil-engined, from the same manufacturer, thus making for ease of comparison between these two particular types..

The best way to begin is to deal first with the purchase tax. The operator can then calculate what it is likely to amount to in the case of a new vehicle which he may have on order, and of which he is expecting reasonably early delivery. Example No. 1, a long-wheelbase, sided lorry, painted, lettered and ready for the road, cost, until April 30, £660. What will it cost to-day? In the first place purchase tax is not calculated on the retail selling price of the vehicles but on the price charged by the manufacturer to the distributor. The precise percentage in relation to the retail price can differ a little between manufacturers, depending to some extent on the margin between manufacturing cost and retail price. I have been informed that -a reasonable approximation of 331 per cent of the wholesale price is 28 per cent. of the retail price. Thus the £660 vehicle, for example, will cost 28 per cent, more, the total amount of purchase tax being £182. The new price will, therefore, be £.842.

For my second example 1 will take a petrol-engined 5-6-tonner of the more expensive type, costing, only recently, £1,165. The purchase tax will be £323 and the new price will thus be £1,488. The third example is also one of the more expensive 5-6-tonners, this time an oil-engined vehicle, which up to the beginning of May could be bought, fitted with the same type of body and suitably painted and lettered. for £1,320. The increment due to purchase tax will in this case be £370 and the new price will, therefore, be £1,690.

The Bright Side The cost of the second petrol-engined vehicle does appear somewhat frightening, and it may be as well before going on with the main theme of this article to look on the bright side. The Chancellor of the Exchequer has a habit of returning with one hand some, if not all, of what he takes away with the other. Not many years ago an alteration was made in the laws governing income tax which is perpetuated in this year's Finance Act. This was designed to encourage the purchase of new equipment and machinery of all kinds, including new commercial vehicles by hauliers. It provided for an initial allowance, to be set off against earnings, of 40 per cent. of the capital outlay on the new equipment.

In the case of commercial vehicles an additional 25 per cent, per annum is allowed for wear and tear. That means that the haulier who buys a new vehicle and pays this extravagant purchase tax will have in artclitibrial rebali-of income tax. Now the outlay on the -first example is £842, and the initial allowanee in the first year of 40 per cent. amounts to £337, and the wear and tear allowance of 25 per cent. amounts to £210. The total is £547, and if income tax be assumed at the rate f• 9s, in the £, that means a :rebate of £246, bringing the total from £842 to £596.

In the case of the second example costing £1,488, the initial allowance is £595 and the wear and tear allowance for the first year 1.372,. a total of £967. equivalent to a rebate of £435 and reducing the capital sum involved to £1,053. Simiiarly, with the third. example the rebate of income tax on the original cost of £1,690 is £495. bringing the cost down to £1,195.

Nowadays, hauliers are not allowed all of the total originally invested in the vehicle during the years when the allowance of 25 per cent. wear and tear on the depreciated value of the vehicle is allowed. The advantage is confined solely to the first year, when it dues serve the purpose of making it easier for an operator to purchase new equipment—in this case new rolling stock.

Wrong Approach

Turning now to the more mundane aspects of this business of calculating what the actual increases in operating costs are, we find that the main item involved is. of course, depreciation. Here I am up against a difficulty as there • may be a tendency for operators who have been fortunate enough to purchase their equipment before May I to deem it unnecessary to take purchase tax into consideration when assessing the increases which they should make in their charges. This view is entirely wrong.

Let me once more stress the point that the assessment of depreciation with a view to determining rates, as based on operating costs, should be interpreted as the provision which the operator makes by way of a sinking fund towards the ultimate replacement, of his present vehicle. Replacements will not be made at the old price, and depreciation figures, therefore, must always be based on current prices of new vehicles. I hope I have made that point clear, for it is most important.

In the first example, the low-priced, petrol-engined 5-6-tonner, 0.98d. per mile would have to be set aside in this way for depreciation calculated on the old price. That figure is arrived at by the method I have so often described. First deduct the cost of six 35 by 7.5 tyres (£120) from the £660— leaving £540. Take away the residual value, approximately 10 per cent. of the £540--1 will assume that to be E50—and 'we get £490 on the .basis of a life of 120,000 miles—which given us 0.9.8d. 1n the case of a vehicle at the new price of £842, the figures are £842 less £120 for tyres, leaving 022. less £72 for residual value, 1650, depreciation figure 1.30d.

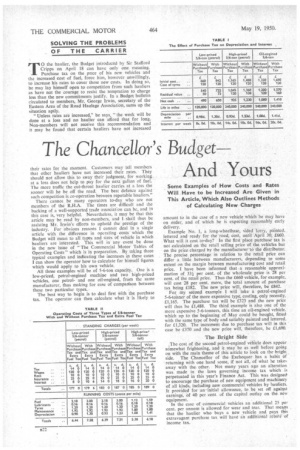

The amounts to be allowed for depreciation in the other examples are: for the second petrol-engined vehicle, the old price was £1,065, arid depreciation amounted to 0.93d., the new price being £1,488, depreciation total 1.23d. In the third example, the old price was £1,320, and depreciation came to 1.08d. At the new price of £1,690, depreciation is 1.41d. These figures, as well as the amounts to be deducted against interest, are shown in Table I.

No doubt every reader will have some idea of how to calculate what the extra 9d. per gallon in the fuel tax wilt mean.

First, the fuel consumption rate of which the vehicle is capable must be known. In the petrol-engined examples under consideration I have assumed an average of 11 m.p.g. The next thing to know is the price which was being paid for the fuel before the increase in tax. The prices which hauliers pay dffer according to circumstances. Some pay retail prices, others bulk prices. Large users geta further rebate on the bulk prices so that cost pergallon varies. I am going to assume that the price paid before the Budget was 2s. per gallon and that it is now 2s. 9d. That being so, the cost of petrol per mile before the additional tax was applied was 2.I8d. Now it is 33d, divided by it— exactly 3d. per mile.

Cost of Oilers

With the oil-engined vehicles I am assuming that the consumption rate is 19 miles per gallon, that the price before the imposition of the extra tax was Is. 9kel., and that it is now 2s. 6fd. The cost per mile for the oilen,gined vehicle was, therefore, I.12d. per mile and it is now 1.59d. per mile.

In Table II I have drawn up schedules of operating costs for the three types, giving in each case the cost before the addition of the purchase tax and the extra fuel tax, as well as the present cost of vehicles and fuel. The standing charges have altered little, and apart from interest the maximum difference is 4s. per week.

It'is in the running costs that the big increases are seen, because two of the five items of running costs have increased, i.e., fuel and depreciation. The important figure, of course, is the total cost per week and I have worked that out and shown it in Table III. To cover a reasonable amount of ground I have taken three figures for weekly mileage in each case, 400, 600 and 800. As may he expected, the greater the weekly mileage the greater the increase in cost. In the first example, the increase rises from 10 per cent. at 400 to 13 per cent. at 800 miles per week, and the actual difference in costs per week in the last case is practically £4.

The oil-engined vehicle, of course, shows to advantage, as it is bound to do to an increasing degree as the price of fuel increases, for the simple reason that it runs more miles per gallon, and the more mites per gallon an owner can get out of his vehicle the less important is the cost of fuel per mile, S.T.R.