WHY TONS OF POTATOES, AND NEW, GO BY ROAD

Page 42

Page 43

Page 44

Page 45

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

• S.T.R. Says That Potato Transport is Tending More and More to be Carried Out by Commercial Motors

Rail Transport, for This Trade, Has Serious Disadvantages, From the Points of View of Producer and Receiver

pOTATO traffic is tending more and more, each year, to be road-borne. Moreover, the tendency became more pronounced after the passing of the Road and Rail Traffic Act. Referring to some notes I made at the time the Act was being placed upon the Statute Book, I find that my records show that rail was generally preferred, notwithstanding certain outstanding disadvantages, such as delays due to double and treble handling, the practice of closing rural goods stations at 4 p.m. and so on.

Opinions to-day, gathered during a tour of Lincolnshire, and as the result of interviews with London merchants, have veered strongly in the direction of a preference for road transport. That is so, even if only old potatoes be considered. New potatoes, according to the majority, should certainly be carried by road.

Take old potatoes first, as forming the major part of a year's traffic and, therefore, being of prior importance. Considering transport broadly, the best way to deliver them—I am quoting merchants and growers—is by road, direct from farm to retailers' shops. This may seem to be so obvious as to need no argument. It is not, however, always convenient or possible to effect deliveries in that way because conditions, such as weight of individual consignments and trade practices, make it impracticable.

It is useful, at this juncture, to indicate the outstanding advantages of being able to deliver direct. In this, I am quoting a well known and leading Lincolnshire merchant. He says: "If a customer telephones to-day and says he wants a delivery of potatoes to-morrow morning, road transport is, in the majority of cases, the only way by which his requirements can be met.

Fib One of the advantages of this method of conveyance is that it has eliminated the need for so many depots and storage places. In the old days, before we could rely upon road transport, depots had to be maintained in every principal centre. They were kept stocked with potatoes sent by rail. Then customers' orders could be met quickly out of stock.

"There is another point, too, worth noting in this connection, and that is that the buyer saves expense if

the deliveries be made direct. If the potatoes are to be taken from a depot, then the customer probably has to send his own lorry to fetch them and has to pay porterage for getting potatoes from store into his vehicle. If the potatoes be delivered direct, his only expenditure Is a tip to the lorry driver."

As a consequence of these advantages, merchants encourage their retailers to have potatoes delivered direct and the retailers themselves are inclined to pro

vide small storage space for their potatoes, so that they can more conveniently accept a consignment sufficiently large to justify a direct delivery.

A further and more recent development of this, is that many big buyers of potatoes in the large cities habitually send their own vehicles daily to the potato-growing centres to collect their supplies, arranging for them to be delivered direct to retail shops.

Asked further to explain what he meant by retailers finding it advisable to provide storage, so that they could have their potatoes delivered direct, this merchant pointed out that there is a limitation to the load which can economically be delivered in that way. It is too expensive to take a load of a couple of tons from, say. Spalding to London, but five tons can conveniently be taken, so that it is up to the retailer to arrange his orders so that he can accept five tons or thereabouts per load.

Actually, of course, only a limited quantity of potatoes goes direct to the retail shop. Most of those sold reach the retailer either through the market or through merchants having warehouses or depots to accommodate large stocks.

In this connection, the balance of convenience is fairly even, as between road and rail. In the markets there are some merchants who prefer a steady flow of produce through their stands. They are able to assess their requirements and sales with a fair degree of accuracy, and place their orders accordingly, so that only a small storage space is necessary just to cover any margin of error as between quantities ordered and quantities sold in any one day. '

On the other hand, a good deal of potato-selling is

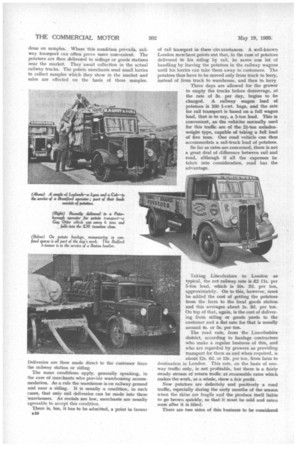

done on sample& Where this condition, prevails, railway transport can often prove more convenient. The potatoes are then delivered to sidings or goods stations near the market. They await collection in the actual railway trucks. The potato merchants send small lorries to collect samples which they show in the market and sales are effected on the basis of these samples.

Deliveries are then made direct to the customer from the railway station or siding.

The same conditions apply, generally speaking, in the case of merchants who provide warehousing accommodation. As a rule the warehouse is on railway ground and near a siding. It is usually a condition, in such cases, that only rail deliveries can be made into these warehouses. As rentals are low, merchants are usually agreeable to accept this condition.

There is, too, it has to be admitted, a point in favour Ble

of rail transport in these circumstances. A well-known London merchant points out that, in the case of potatoes delivered to his siding by rail, he saves one lot of handling by leaving the potatoes in the railway wagons until his lorries can take them away to customers. The potatoes thus have to be moved only from truck to lorry, instead of from truck to warehouse, and then to lorry Three days are allowed for the grower to empty the trucks before demurrage, at the rate of 3s. per day, begins to be charged. A railway wagon load of potatoes is 100 1-cwt. bags, and the rate for rail transport is based on a full wagon load, that is to say, a 5-ton load. This is convenient, as the vehicles normally used for this traffic are of the 2i-ton unladenweight type, capable of taking a full load of five tons. One road vehicle can thus accommodate a rail-truck load of potatoes.

So far as rates are concerned, there is not a great deal of difference between rail and road, although if all the expenses be taken into consideration, road has the advantage.

Taking Lincolnshire to London as typical, the net railway rate is £.2 lis. per 5-ton load, which is I0e. 2d. per ton, approximately. On to this, however, must be added the cost of getting the potatoes from the farm to the local goods station and this averages about Is. 0th per ton. On top of that, again, is the cost of delivering from siding or goods yards to the customer and a flat rate for that is usually around 4s. or 5s. per ton.

The road rate, from the Lincolnshire district, according to haulage contractors who make a regular business of this, and who are regarded by growers as providing transport for them as and when required, is about 12s. 6d. or 13s. per ton, from farm to destination in London. This rate, on the basis of oneway traffic only, is not profitable, but there is a fairly steady stream of return traffic at reasonable rates which makes the work, as a whole,. show a fair profit.

New potatoes are definitely and positively a road traffic, especially during the early months of the season when the skins are fragile and the produce itself liable to go brown quickly, so that it must be sold and eaten soon after it is lifted.

There axe two sides of this business to be considered ----imported produce from Jersey and English-grown produce. The season for Jersey potatoes has just started ; this article is actually timed to appear as the first hulk cargoes are arriving. The season lasts about 3; months. In England, new potatoes begin to appear on the market, in any quantity, only about a month later than Jerseys, starting. that is to say, about the middle of June.

Transit Delays Affect Market Prices.

Quite apart from the delicate nature of new potatoes, which prevails only for about the first three or four weeks of the season, it is the fact that they find a much better market if they can be brought from the field to the stand or ship while there is still the bloom upon them. That bloom is lost if they be a day or more in transit.

Since, however, railway companies, generally speaking, accept traffic in rural stations up to only 4 o'clock in the afternoon, whereas road vehicles can be loaded up to 6, 7 or even 8 o'clock in the evening and still have the potatoes on the market the first thing next morning, the advantage obviously lies with road transport.

The importance of the time factor is equally great in respect of the Jersey potato trade. There are bigger daily fluctuations in prices, as well as in quantifies arriving and if, for any reason, a day be lost then that may involve a difference of as much as 10s. per barrel. This is the merchant's loss, but the sender bears some of it, since he is often paid on commission.

Delays involving such loss are more likely to happen if the potatoes come by rail than if they come by road.. Further, as the 'disease of blight is prevalent in Jersey

potatoes. during wet weather, delay in getting these potatoes on the market may result in a total loss.

At the same time, according to some of my informants, there are snags even in connection with road transport. One may arise if a consignee be a man in a comparatively small way of business, so that his individual consignment is a small one and part of a big load. If the rest of the load be for a bigger customer, there is a tendency to deliver that first and the smaller consignee receives his potatoes late and loses the best market price.

So far as rates are concerned, the all-in tariff from Jersey, through to London and other destinations in the United Kingdom, is the same whether the traffic overktnd be carried by road or by rail. There is, therefore, having in mind the inducements above named, every reason why the merchant should prefer to have his new potatoes conveyed by road.

Avoiding Trouble of Split Loads.

Burrows Transport, Ltd., a concern which makes a speciality.of conveyance of new potatoes from Portsmouth, in reply to the criticism made above about split loads, states that steps have been taken to avoid any such trouble. Produce for transport by the company is loaded at Portsmouth in such a way as to avoid having too many deliveries on a single vehicle. It is known, as the result of years of experience which of the consignees are open all night to accept deliveries. Further, a list is kept showing times at which all consignees in the main markets will accept delivery. The vehicles are loaded accordingly and the last loads are usually delivered shortly before midnight.