Moo-ving in the

Page 21

Page 22

Page 23

Page 24

Page 25

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

right direction

Milk collection specialist SJ Bargh came perilously close to exiting the industry, but now it has become a leading player thanks to acquisition and organic growth

Words: Kevin Swallow / Images: Tom Cunningham

Between 1933 and 1994 the government

run Milk Marketing Board (MMB) controlled milk production and distribution in the UK. In 1970 it began its biggest modernisation programme, moving from milk churns to tankers, forcing farmers to install new vats to store milk before collection.

It was a slow process and the MMB allocated tankers piecemeal to contracted hauliers as the number of vats increased. When it assigned two tankers to Milnthorpe haulier K Fell, it left neighbouring operator SJ Bargh, based in Caton, out in the cold, despite having 35 years’ experience collecting milk.

Fortunately, explains SJ Bargh MD Stuart Cornthwaite, K Fell decided it didn’t want to continue collecting milk. “We would have had to pack up, because you either had a contact with the MMB or you didn’t. The MMB asked us to take the vehicles on.” He recalls the frst two tankers well: “They were VTJ 301H and VTJ 302H BMC Mastiffs, with Perkins V8 engines and Thompson Carmichael tanks still in K Fell livery. The trucks were useless.” Cornthwaite joined SJ Bargh in 1970 as a trainee itter, helping maintain 12 latbed churn collection vehicles and three vehicles on general haulage. By 1975, with the move to tank collection complete, he was working in the transport ofice. “My job was running the trucks and getting the backloads, and that expanded into the role of transport manager,” he says.

After supervising the company’s irst steps in the free market following deregulation of the MMB in 1994, he replaced John Gott as MD in 1995.

The MMB’s successor was Milk Marque (the dairy farmers’ marketing co-op), but the Agriculture Act 1993 allowed farmers to sell milk to anyone. That changed the industry and SJ Bargh now had to compete in an ever-changing landscape with major logistics companies.

Replacement vehicles

Free of the government’s shackles, the company replaced the nine MMB-specced 9,000-litrecapacity vehicles with 21,000-litre rear-steer tanker trailers and drawbar combinations. “That was driven by local farmers who signed with direct buyer MD Foods [now Arla Foods] and we got that job to collect the milk,” he says.

Between 2000 and 2002 he served as chairman of the Transport Association (TA), which the company joined in the 1980s. His stewardship of the TA coincided with three major events. First, the government, concerned with monopolies, announced a shake-up of milk supply and subsequently Milk Marque was split into three regional co-ops: Axis, Milk Link and Zenith.

Second, when local farmers joined the Milk Group co-op, SJ Bargh picked up the work and eventually became the sole north-west collector at the expense of Slater Haulage, based at Longridge, Preston. SJ Bargh bought the company’s assets to cope with the additional work.

Third, in 2002 the Milk Group and Zenith combined to form Dairy Farmers of Britain (DFoB), which marketed more than 1.3 billion litres of milk a year from more than 2,000 farms.

It rationalised its haulage operation, with SJ Bargh and two fellow hauliers winning the work. In January 2009, SJ Bargh made its second purchase, buying the assets and inheriting drivers from Weaver Logistics, based in Endon, Stoke-on-Trent, expanding the leet by 40%. It collected for several processors across the Midlands.

“The deal widened our customer base when there was rationalisation in the industry and it strengthened our position,” Cornthwaite says.

Then the following June, DFoB went into receivership. “It was one of the biggest challenges we have had; DFoB was one of our biggest customers. It was horrendous for several months,” he says.

Organic growth

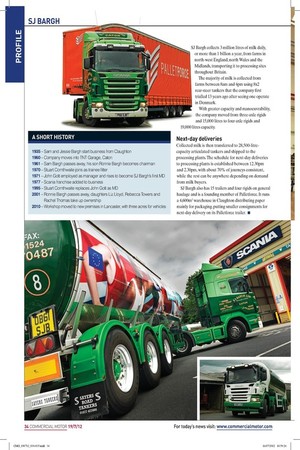

But what emerged from the DFoB failure was unexpected. “Farmers associated with DFoB joined other direct buyers or co-ops that we had contracts with and we expanded organically as a business, despite losing such a major customer,” he explains. “Milk Link signed a lot up and bought a creamery in north Wales from DFoB. It asked us to pick the milk up and transport it.” From almost missing out during the transition from churn to tanker, today SJ Bargh collects 3 million litres of milk daily, or more than 1 billion a year, from farms in north-west England, north Wales and the Midlands, transporting it to processing sites throughout Britain.

The majority of milk is collected from farms between 8am and 4pm using 8x2 rear-steer tankers that the company irst trialled 13 years ago after seeing one operate in Denmark.

With greater capacity and manoeuvrability, the company moved from three-axle rigids and 15,000 litres to four-axle rigids and 19,000 litres capacity.

Next-day deliveries

Collected milk is then transferred to 28,500-litrecapacity articulated tankers and shipped to the processing plants. The schedule for next-day deliveries to processing plants is established between 12.30pm and 2.30pm, with about 70% of journeys consistent, while the rest can be anywhere depending on demand from milk buyers.

SJ Bargh also has 15 trailers and four rigids on general haulage and is a founding member of Palletforce. It runs a 4,600m2 warehouse in Claughton distributing paper mainly for packaging, putting smaller consignments for next-day delivery on its Palletforce trailer. ■

CONTRACTS

All of SJ Bargh’s contracts are with milk buyers (also known as direct buyers, processors, dairies and co-ops) to collect milk from farms and deliver it to processing plants. There is no contract with farmers, only day-to-day interaction.

Staff from Weaver Logistics joining SJ Bargh included commercial manager Michael Sidley. As commercial director, his remit is winning new work, retaining contracts, and working with customers.

Two recent deals underline his work – a contract extension with Dairy Crest to collect non-organic and organic milk, and a new three-year contract with organic dairy co-operative OMSCO to collect more than 50 million litres of milk annually from organic farms in central England, north Wales, Lancashire and parts of Yorkshire. It is SJ Bargh’s first 100% organic milk contract.

“Milk fields [an area with a group of farms producing milk] tend to be dense in rural areas, whereas organic milk farms tend to be more dispersed,” he says. “It’s more expensive to collect, we put in a higher price than we would for collecting non-organic milk, but margins remain identical for both types of work.” Organic milk remains a niche product but, more importantly, OMSCO is an extra customer in the industry. Aside from the acquisitions, most growth is through existing contracts. “We depend on how many farms they are able to sign and their growth patterns,” he says.

Most milk buyers prefer fixed-price contracts over open contracts as they enable dairies to negotiate with retailers using a fixed-cost, pence-per-litre of milk collected. “The problem we have is predicting the amount of milk we’ll collect across the contract term. We are being paid on the basis of our costs divisible by the milk we collect,” he says.

To create efficiencies, SJ Bargh also pools milk collections across areas agreed by separate milk buyers. This allows one vehicle to collect from all the farms in a specific area rather than send two vehicles because there are two contracts. Milk is relatively consistent unless it is going into a specific product. However, supermarkets prefer segregated milk pools and ask milk processors to specifically collect from farmers who only meet certain standards.

Like all good contracts, there are surcharges and trigger mechanisms in place for fuel and changes in volume, as well as a continued dialogue around the ‘what if?’ question.

Sidley explains: “If we create an efficiency, we might see a drop of vehicles within the fleet, pooling two collections might see two sets of 10 vehicles combined but only 18 needed to collect the milk.” He also expresses the importance of the recently achieved Dairy Transport Assurance Scheme (DTAS) code of practice status with Dairy UK that covers subcontractors, vehicle hygiene, site requirements, personnel and training, complaints procedures and record-keeping.

“It’s customer-driven; some contracts state that we must be DTAS-approved, with external audits and internal audits covering the transportation of milk from farm gate to dairy processors,” he says.

A SHORT HISTORY

1935 – Sam and Jessie Bargh start business from Claughton 1960 – Company moves into TNT Garage, Caton 1961 – Sam Bargh passes away, his son Ronnie Bargh becomes chairman 1970 – Stuart Cornthwaite joins as trainee fitter 1971 – John Gott employed as manager and rises to become SJ Bargh’s first MD 1977 – Scania franchise added to business 1995 – Stuart Cornthwaite replaces John Gott as MD 2001 – Ronnie Bargh passes away, daughters Liz Lloyd, Rebecca Towers and

Rachel Thomas take up ownership

2010 – Workshop moved to new premises in Lancaster, with three acres for vehicles

WORKSHOP

SJ Bargh moved into its TNT Garage in Caton, Lancashire in 1960, and for almost 50 years maintained the fleet from its three-bay workshop. In 1977 it added the Scania parts and service franchise, thanks to former MD John Gott. Current MD Stuart Cornthwaite explains: “We operate 365/24, so limiting downtime is important. If other places are closed on a Sunday, we can provide the part ourselves, plus, at the time, there was a big void between the nearest Scania dealers – Carlisle and Manchester.” Despite running shifts to use the workshop, by 2009 SJ Bargh outgrew it. It acquired five acres from Lancasterbased Dennison Trailers and moved into a 12-bay workshop in 2010, three miles west of Caton. The remaining three acres will eventually house the milk collection fleet, still based at the TNT Garage.

The workshop includes new authorised testing facilities (ATFs). With the nearest Vosa test stations at Milnthorpe and Kirkham, the company saves £16,000 a year on fuel by testing its own fleet, helping the site pay for itself within seven years (CM 26 April).

A newly installed tachograph bay also drives down future costs as well as reaping longer-term benefits with third-party work. “By adding these things to the workshop we are creating a one-stop-shop for us and retail work,” says general manager of fleet service and parts Steve Thompson (pictured).

There are 11 technicians, with two apprentices due to start work, who provide 600 hours for the company to sell each week. A unique selling point, he says, is that the workshop delivers “fleet maintenance by a fleet operator. That is a bit unusual in the marketplace because most franchise workshops don’t have that day-to-day experience of running a fleet,” he says.

SJ Bargh tends to keep trucks and trailers as long as they remain viable, and it’s a philosophy born from the days of the Milk Marketing Board, which specified how long a vehicle remained on the fleet: eight years for the chassis and 16 years for the tank.

With Euro-6 on the horizon, the company will be ordering 10 new tanker trailers, five eight-wheelers and 14 new and used tractor units. “It’s more tractor units than usual to get the fleet compliant with London’s Low Emission Zone,” he says. “About 20% of the work goes into London.” Tankers are built by either Crosslands, Clayton Commercials or Sayers (Northallerton) and the four-axle milk collection trucks are fitted with pumping gear from either Gardner Denver or Piper Systems.

The next step is to invest more in the Endon workshop, which has six technicians. “There is a fleet management system, 2.5 lanes, and we have bought diagnostic equipment for that site. It has 24-hour breakdown recovery call now,” he says.