LEADER OF

Page 38

Page 39

If you've noticed an error in this article please click here to report it so we can fix it.

THE PACK

When you own exactly three vans, talking of taking on the major players in international haulage might seem confident to the point of being foolhardy. But the men behind Silver Wolf have enough of a track record to be taken very seriously.

• "People say there's no work around. That's a lot of nonsense. Of course there's work — you've just got to know where to find it." That's the view of Bill Batho and Derek Beevor, and they've put their money where their mouths are by forming a new company, Silver Wolf Transportation, to offer international distribution.

The company is Batho's idea. He argues that as the Single European Market develops the traditional areas of profit for freight forwarders — Customs clearance and documentation — will become obsolete, leaving forwarders to make their money from the haulage element. This will entail a subtle but important change: instead of seeing vehicles as a cost and a necessary evil, they will have to think of the fleet as a profit centre.

"The problem with the big companies is they know in their heart that's the situation, but they don't like change," says Batho, and true to its name the new company aims to be a wolf at the door of those forwarders who cannot, or will not, adapt to the rigours of efficient haulage.

Batho knows the business well. He spent 12 years at Martintrux, leaving in 1987 because the firm would not haul directly for shippers, rather than forwarders. Two years later, as he expected, the company had to call in the receivers.

Meanwhile he had become UK and northern European operations director of MedTrans, a large forwarder which, says Batho, had recognised the need "to get its transport act together". But after three years with the company, he has quit to exploit what he sees as a largely untapped niche in the market.

"I see myself as a haulier and Silver Wolf as an international distribution company," he says. The company is targeting contracts for consignments which do not fit neatly with either a parcels carrier or a pallet-load haulier. Typical of its contracts is one for flat-pack furniture brought in from France, where packages come in many shapes and sizes. He is also looking for business from high tech companies which are "not totally happy" with parcels carriers.

Batho was planning on doing the job on his own until he got talking to Beevor, the joint owner of the computer software house, Road Tech, which is the leading supplier of traffic management packages to hauliers. Road Tech's customer list includes many of the best-known names in the business, particularly among the private companies, so it was an obvious choice of supplier when Batho decided to buy a computer. He got his computer but also came away with a partner who had financial clout, a ready-made operating base and office, and experience of setting up a company from scratch. All of these assets have proved useful, he says.

Silver Wolf shares the Watford base of Tudor Transport, a small general haulage and storage firm which Beevor owns, although the two firms operate separately.

That computer has proved its worth too: "If it wasn't for the computer I'd have four people in the traffic office, not one," says Batho. "The offices — just two small rooms — don't look much, but the last thing a new company needs are high overheads, either in staff or plush offices."

Beevor is continuing to expand Road Tech in Britain and is now taking it on to the Continent, so he doesn't actually need the money, but Silver Wolf is the sort of project offering fast growth on which he thrives. "Money in the bank is just like a points system," he says. Especially when you've got a lot of it.

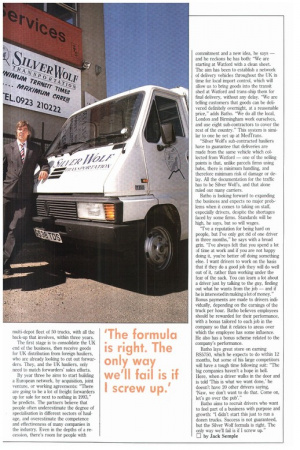

Batho and Beevor are talking big, from a small base. They only operate three vans of their own at present, which rather neatly avoids the inconvenience of licensing, for the time being. They have an art c and a 17-tonner in company livery run by owner-drivers. But Beevor envisages a

multi-depot fleet of 50 trucks, with all the back-up that involves, within three years.

The first stage is to consolidate the UK end of the business, then receive goods for UK distribution from foreign hauliers, who are already looking to cut out forwarders. They, and the UK hauliers, only need to match forwarders' sales efforts.

By year three he aims to start building a European network, by acquisition, joint venture, or working agreements: "There are going to be a lot of freight forwarders up for sale for next to nothing in 1993," he predicts. The partners believe that people often underestimate the degree of specialisation in different sectors of haulage, and overestimate the competence and effectiveness of many companies in the industry. Even in the depths of a recession, there's room for people with commitment and a new idea, he says — and he reckons he has both: "We are starting at Watford with a clean sheet. The aim has been to establish a network of delivery vehicles throughout the UK in time for local import control, which will allow us to bring goods into the transit shed at Watford and trans-ship them for final delivery, without any delay. "We are telling customers that goods can be delivered definitely overnight, at a reasonable price," adds Batho. "We do all the local, London and Birmingham work ourselves, and use eight sub-contractors to cover the rest of the country." This system is similar to one he set up at MedTrans.

"Silver Wolf's sub-contracted hauliers have to guarantee that deliveries are made from the same vehicle which collected from Watford — one of the selling points is that, unlike parcels firms using hubs, there is minimum handling, and therefore minimum risk of damage or delay. All the documentation for the traffic has to be Silver Wolf's, and that alone ruled out many carriers.

Batho is looking forward to expanding the business and expects no major problems when it comes to taking on staff, especially drivers, despite the shortages faced by some firms. Standards will be high, he says, but so will wages.

"I've a reputation for being hard on people, but I've only got rid of one driver in three months," he says with a broad grin. "I've always felt that you spend a lot of time at work and if you are not happy doing it, you're better off doing something else. I want drivers to work on the basis that if they do a good job they will do well out of it, rather than working under the fear of the sack. You can learn a lot about a driver just by talking to the guy, finding out what he wants from the job — and if he is interested in making a lot of money." Bonus payments are made to drivers individually, depending on the earnings of the truck per hour. Batho believes employees should be rewarded for their performance, with a bonus tailored to each job in the company so that it relates to areas over which the employee has some influence. He also has a bonus scheme related to the company's performance.

Batho lays great store on earning BS5750, which he expects to do within 12 months, but some of his large competitors will have a tough time following suit: "The big companies haven't a hope in hell. Here, when a driver walks in the door and is told This is what we want done,' he doesn't have 20 other drivers saying, 'Naw, we don't want to do that. Come on, let's go over the pub'."

Batho aims to recruit drivers who want to feel part of a business with purpose and growth: "I didn't start this just to run a dozen trucks. Success is not guaranteed, but the Silver Wolf formula is right. The only way we'll fail is if I screw up." 111 by Jack Semple